Interview: Norah Labiner

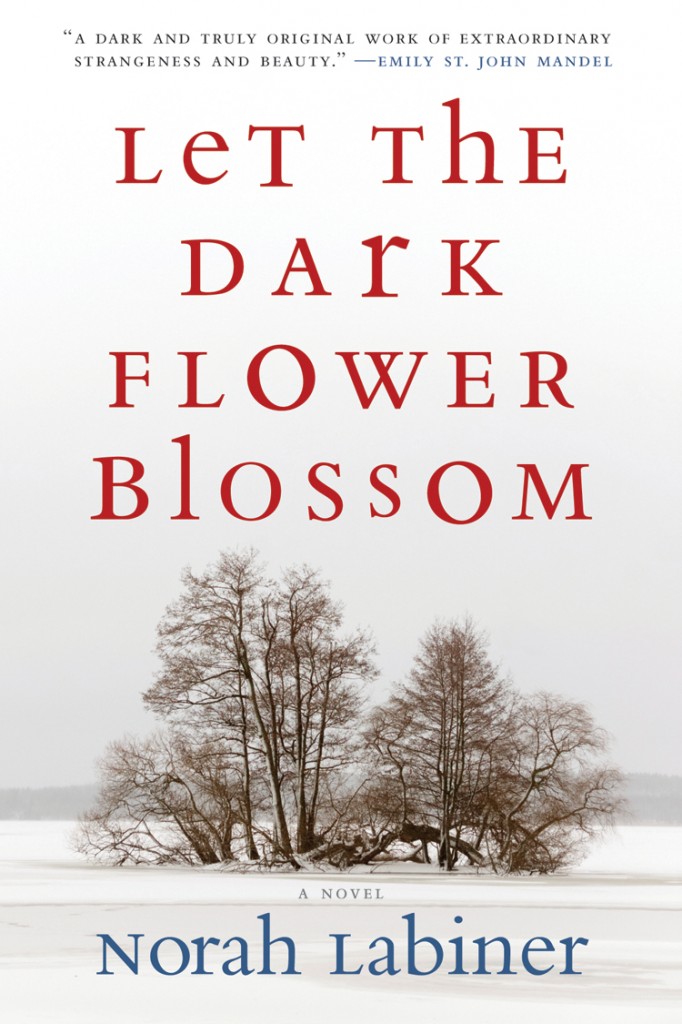

Norah Labiner is the author of the novels Our Sometime Sister, Miniatures, German for Travelers, and, most recently, Let the Dark Flower Blossom (Coffee House Press). She has received a Minnesota Book Award for Literary Fiction and fellowships from the Minnesota State Arts Board, the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, and the National Endowment for the Arts. Her work has been recognized by the American Library Association, the Jewish Book Council, and the Barnes & Noble Discover Great New Writers series.

Norah Labiner is the author of the novels Our Sometime Sister, Miniatures, German for Travelers, and, most recently, Let the Dark Flower Blossom (Coffee House Press). She has received a Minnesota Book Award for Literary Fiction and fellowships from the Minnesota State Arts Board, the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, and the National Endowment for the Arts. Her work has been recognized by the American Library Association, the Jewish Book Council, and the Barnes & Noble Discover Great New Writers series.

(Photographer credit: Michael Wisti)

Midwestern Gothic: First things first, tell us about your Midwestern roots.

Norah Labiner: I’m from Flint, Michigan—when I was a child, it became a ghost town overnight. It was like a city in a zombie movie. The stores were shuttered and the people were gone. For a while it was the per capita murder capital of the country, and in school we all thought this was really fantastic. I stayed up late reading books about other places. Trains ran all night; I could hear them from my bedroom window. I wondered where they were going. Everyone dreamed of escape. Everyone talked politics. Everyone hated Reagan. Everyone talked about moving to Canada. I would ride my bike to the public library. I loved watching old movies on Channel 50 out of Detroit: the Creature Feature and the Ghoul and Sir Graves Ghastly. I had a Smith Corona typewriter. I wanted to write novels. I went for a time to Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio, then to the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. Everyone talked about postmodernism. Everyone read Bukowski. Everyone talked about moving to Seattle. I lived in the last house on State Street, right by the train station. The house was rumored to be haunted by the ghost of a girl who had thrown herself on the railroad tracks. I never saw the ghost. I’ve lived in Minnesota for many years now. Everyone recycles, everyone rides a bike, everyone is working on a novel.

MG: Critics have said of your past novels that you use a sort of “nuanced, experimental” form in your prose. How would you define your writing style and is there anything in Let the Dark Flower Blossom, style-wise, that sets it apart from your past publications, like Miniatures, Our Sometime Sister, and German for Travelers?

NL: My writing is as nuanced as a baseball bat.

MG: This novel is essentially a murder mystery, as the plot moves from the murder of Roman Stone, a literary celebrity—did you always see yourself writing in or drawn to this genre?

NL: I love the old stories, the ones about jealous gods and broken idols. There are certain stories that appear again and again throughout history: the murder of a king, the rape of a beautiful girl, the birth of a divine child. I wanted to tell a story that worked these three mythological obsessions together. I wanted to tell a story about a murder and its consequences. So Let the Dark Flower Blossom is a murder mystery about why we love murder mysteries, and what this love says about us. As for me? I think—and I hope—that the best sort of mystery is a philosophical enterprise and a theoretical ziggurat and plot-twisting thriller for the reader and writer alike.

MG: How did you decide on the setting of this novel, rooted in Chicago?

NL: The book has an ornate crypto-nesting doll structure—a box inside a box, a story inside a story, a place inside a place, a postcard of a place, a place inside a book—: there is an island in Wisconsin; a garden in Omena, Michigan; a farmhouse in South Dakota; the college town of Virgil’s Grove, Iowa; the sleepy streets of Little America, Minnesota; and the rose-wreathed gloom of the Parliament Hotel in Chicago. The characters go from place to place, from room to room, from bed to balcony. And they have one thing in common: they are all exiles. They dream of escape—whether it is to the past or to Hollywood or to a world of their own creation. They are trying to escape the confines of the book; impossibility is always a possibility.

MG: As more people are self-publishing books and in blog-formats online, how do you maintain a voice uniquely your own, fending off outside influence from your style?

NL: Just tell the story. Start with the story. Tell your story. What else matters? Blogs, presses, magazines, publishing houses—these are only means of disseminating the story. It’s true: everything happens all the time. And the Internet and its myriad publishing possibilities allow for heaps of stories—but you can’t let the machine mean more to you than the ghost. That is, no artist should worry about fending off outside influence. Your voice is your art. If you are influenced by something—whether it is Proust or a picture of a cat eating pancakes—this is part of your voice. Your voice is a function of how you take in the world. You translate imagery into language. And language is always changing. The moment is always changing. It’s beautiful. It’s madding. It’s a mystery! Who would want it to be otherwise? Be brave. Be fantastic. Don’t write defensively. Think about it: you are the one telling the story. The world should be worried about fending off you.

MG: As someone with Midwestern roots, how would you define the Midwest?

NL: A haiku written on the wall of a gas station bathroom in Gary, Indiana.

MG: At Midwestern Gothic, we often focus on how the region is somewhat overlooked, from a cultural/literary perspective. Why do you think this is or isn’t the case?

NL: The Midwest is overlooked, but I would argue that the best thing for art or for an artist is to be overlooked. Maybe—like the exiles and escapists in my books—I’m a little superstitious.

MG: What’s your favorite state in the Midwest and why?

NL: Minnesota is a good place for a writer. The winters are long and cold and miserable. The summers are relentless. It’s a tolerant place, but it’s not very forgiving. It can be cruel. It’s a place that doesn’t take well to ambition. The unofficial state motto is “Just who do you think you are?” Fitzgerald called the Midwest, “the ragged edge of the universe.” He also never stopped calling it home. There is a life-sized statue of Fitzgerald in a park in downtown St. Paul. From a distance, or in the evening as you leave the library and walk to the bus stop, it looks, it seems like he is a real person, waiting. He waits all winter with no coat. He stands in summer holding his hat, with pigeons at his feet. He is there now. You can see him night and day waiting. Is this sad or is it funny? Places will punish you. They will punish you for leaving. And they will punish you for staying. In Minneapolis you can walk across the bridge over the Mississippi from which John Berryman jumped to his death. Hundreds, who knows? thousands of students cross it every day. And no one ever looks down. I don’t mean to be morbid, or maybe I do, but the Midwest has a dark heart.

MG: What novel would you suggest for aspiring writers to read?

NL: The Journal of Albion Moonlight by Kenneth Patchen. It’s my favorite book, but I have absolutely no idea what happens in it. So if someone out there would read it, and then write to me with an explication or send a pen & ink sketch, by way of interpretation—I would be eternally grateful.

MG: What’s up next for you?

NL: I’m working on a novel set in a fictional Midwestern town in the drought summer of 1900. There is a murder, yes. There is an old house, three clever dogs, an ingenious cat, a beautiful orphan, a mysterious stranger, a lost suitcase, a misplaced axe, and a found manuscript. All of the characters from my previous books will appear in the pages, wearing top hats and corsets, eating raspberry cake, and misquoting lines of poetry.