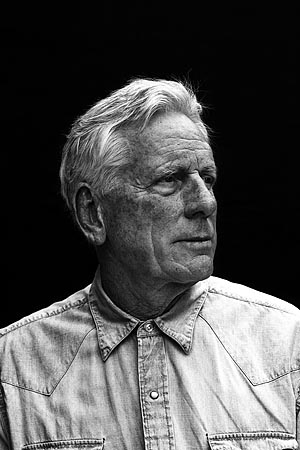

Interview: Thomas McGuane

Midwestern Gothic staffer Jon Michael Darga talked with acclaimed author Thomas McGuane about destiny, directing the film adaptation of his own novel, the role of regionalism in writing, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Jon Michael Darga talked with acclaimed author Thomas McGuane about destiny, directing the film adaptation of his own novel, the role of regionalism in writing, and more.

**

Midwestern Gothic: First and foremost, what is your connection to the Midwest?

Thomas McGuane: I was born in Wyandotte, Michigan, and grew up on Grosse Ile. I studied at Michigan, Olivet, Michigan State where I received a BA, went on to Yale for an MFA and was a Stegner Fellow at Stanford. My breakthrough as a writer was at Olivet where my aspirations were taken seriously for the first time. I moved to Montana by accident and have lived there for the past 46 years.

MG: Your first published novel, The Sporting Club, was set in Michigan; your second, The Bushwhacked Piano, takes its protagonist from Michigan to Montana, shadowing your own move. What role do you think regionalism and setting play in your writing?

TM: I think it’s important for writers to know their territory in persuasive detail. Beyond that, I don’t think regionalism has much merit. Montana is obsessed with regionalism and its best use is as camouflage for mediocre writing.

MG: Several of your books feature the fictional town of Deadrock. What is the significance of this town? Is it just a fun place to return to, or are there wider thematic elements you hope to portray across its landscape?

TM: Deadrock is a local play on the name “Livingston”. My town, Big Timber, is known as Little Sticks. It is in my fiction a somewhat amalgamated place that include the disparate elements around me, ranching , railroading, art galleries, colleges, dope dealers, car thieves, cowboys, etc.

MG: In your latest book, Driving on the Rim, you make note of your main character’s name, Irving Berlin Pickett. What is the significance of a name to you? How do you choose your characters’ names?

MG: In your latest book, Driving on the Rim, you make note of your main character’s name, Irving Berlin Pickett. What is the significance of a name to you? How do you choose your characters’ names?

TM: I just thought that the peculiar parents my protagonist had might have the sort of primitive patriotism to name their child after the author of “God Bless America” without quite foreseeing the absurdity of the name. I suppose it was a comic impulse.

MG: In Driving, you returned to a first-person narrator, which you hadn’t used since 1978’s Panama. Why did you return to first-person forty years later?

TM: Using the first person in this way trades the ability to move around in time, just as our thoughts do, for the disadvantages of limited perspective as compared to the third person. Many writers cheat as I have done by using a third person narration that is so closely held to an individual point of view that it has advantages of both.

MG: Several of your works seem to touch on the theme of destiny. What do you find compelling about the idea of destiny? Does it stem from your personal life?

TM: I’m not sure I have an overarching view of destiny beyond my reservations about individuality and free will. We are distinctly preconditioned genetically, environmentally and culturally within which we have substantial wiggle room. It’s one of the tasks of an artist to see into alien lives and unfamiliar cultures i.e. anyone else.

MG: The blurb for Driving describes Pickett’s realization that “there is meaning to life beyond professional accreditation, even in the noblest of callings” and that Pickett undergoes a sort of spiritual awakening. As you wrote the novel, did you have any realizations about your own life? Did the fiction lead you to learn anything about yourself?

TM: I think the analogy to my own life from Driving on the Rim is that societal accreditation—medicine, war, sport, literature—does not necessarily guarantee anything else about an individual’s life. Doctors can be drug addicts or child molesters, artists can be fascists, war heroes can be bigots, etc. I have had many of the struggles of someone of my time, place and situation but have secured semi-respectability through my work. This is what work does for most of us.

MG: Can you talk a little bit about studying playwriting at Yale and then writing your first novel a few years later, at Stanford? What was your initial draw to playwriting, and why did you end up making the “transition” (though you later returned to screenplays) to novels?

TM: I studied playwriting at Yale because of some encouragement I’d received at Michigan State and because my approach to narrative has been largely driven by dialogue. In the end, writing is writing, one perception should lead to another and stories either sink or swim. There is less distance between fiction, screenwriting and non-fiction than is generally supposed. Examples of each tend to be divided between either good and bad or boring and interesting.

MG: You wrote and directed the film 92 in the Shade, based on your novel Ninety-Two in the Shade. How did that come about? How did you find adapting your own work? Would you do it again?

TM: I directed 92 because the producer Elliot Kastner and the original director Robert Altman had a falling out. To preserve the financing with United Artists, someone had to be found immediately and the job fell to me. I wouldn’t do it again. I thought it was a boring job. Writing fiction is the only thing that really excites me.

MG: What’s next for you?

TM: I have been writing short stories, most published in The New Yorker, Granta and McSweeny’s—and it’s time to collect them for the first of my three book contract with Knopf. I’ll start a novel next but it will be hard to give up stories for the time being. There are wonderful short story writers in the country right now and it’s inspiring to see them at work. They are more interesting than our novelists at this time.

**

Thomas McGuane is the author of ten novels, short fiction and screenplays, as well as three collections of essays devoted to his life in the outdoors. He is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, The National Cutting Horse Association Hall of Fame and the Flyfishing Hall of Fame.