Interview: Vu Tran

Midwestern Gothic staffer Hannah Bates talked with author Vu Tran about Vietnamese-Americans, noir fiction, restless characters, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Hannah Bates talked with author Vu Tran about Vietnamese-Americans, noir fiction, restless characters, and more.

**

Hannah Bates: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Vu Tran: I’ve been teaching at the University of Chicago for the last five years and moved to the city from Las Vegas for that reason. Between 2000 and 2003, I lived in Iowa City when I was studying at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and before that I grew up in Tulsa, which is not geographically the Midwest but always felt culturally Midwestern to me: the small town feel of the city, the focus on family and religion, the general politeness and niceness of everyone, the fact that most people grow up, have a family, and stay in their hometown.

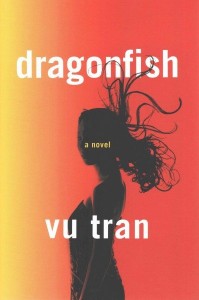

HB: Your debut novel Dragonfish was classified by The New York Times as “new immigrant literature.” What does mingling history-based writing with fiction do in terms of creating an experience that immigrants or first-generation Americans can relate to?

VT: One of the consequences of diaspora is that the immigrant—particularly the refugee who has no agency in their emigration—gradually loses touch with the culture and voice of their homeland, that sense of themselves as purely or authentically any nationality anymore. For Vietnamese-Americans, in particular, Vietnam lives mostly in their memories or their parents’ memories, in their infrequent trips back home, or through the very narrow lense of Hollywood and Vietnam War movies, and this all makes it rather difficult to inhabit an authentic sense of self, especially if they’ve never truly assimilated. I don’t think my book—in its engagement with history—does anything that different than any other kind of fiction that deals with recent history. I didn’t even think of it as history-based necessarily when I was writing it. I was simply trying to dramatize a story about characters who were wounded and shaped by their past circumstances and now carry that trauma with them in the new country, and if that resonates with readers—especially immigrants or first-generation Americans—I’d like to think it’s the melancholy and damaged voice of those characters that resonates, not the politics or the specific historical circumstances.

HB: You state that your writing is largely about the Vietnam War and the individuals that have been affected by it. How much of this preoccupation stems from your own identity as an individual born in Vietnam just after the fall of Saigon? Where is the line between fiction and nonfiction for you?

VT: My father, who fought in the South Vietnamese Air Force and with the Americans, fled the country when Saigon fell in 1975, five months before I was born. Five years later, in 1980, my mother took me and my sister and we escaped the country by boat, landing in Malaysia and staying at a refugee camp there for four months before my father sponsored us to America. So yes, my background definitely motivates my curiosity in the Vietnam War and my desire to write about it and its aftermath. And yes, I’ve drawn from a bit of my own life for my work. But I also wouldn’t call my work nonfiction in any way. The war is simply a framework for the fictional world I’m presenting to the reader, a way of contextualizing the things I’m frankly much more interested in: the ways we try, often unsuccessfully, to deal with our past misfortunes; the ways we try desperately to connect with people who deny us access; the ways we try to access worlds that are out of our reach. And to answer your question more generally and straightforwardly, I don’t think about the line between fiction and nonfiction, mostly because the line is always moving, sometimes even dissolving, depending on what you’re trying to say and how you’re trying to say it. Like many writers, I think fiction can often get at the truth more effectively and profoundly than any factual book can, and when it does, who can then define such an arbitrary line?

HB: The Vietnamese characters in Dragonfish each have Americanized names: Sonny, Happy, Junior, Suzy. Why did you choose these names? Is it necessary for these individuals to alter their names — their identities — in order to fit in?

HB: The Vietnamese characters in Dragonfish each have Americanized names: Sonny, Happy, Junior, Suzy. Why did you choose these names? Is it necessary for these individuals to alter their names — their identities — in order to fit in?

VT: A lot of Asian immigrants choose their Americanized names, not just to fit in, but also because their real names might simply be too hard to pronounce for Americans. In Dragonfish, I don’t clarify why the Vietnamese characters choose those names, but it is important that they all have multiple names. Suzy, for example, is referred to by four different names, and it speaks not only to her liminal status in the world, but also to the fact that no one really knows who she is.

HB: Why did the genre of noir fiction suit Dragonfish? What about the crime framework appeals to you as a writer?

VT: First of all, as the word suggests, noir is about the absence of light, of truth, about the stories that exist in the shadows and are only partially revealed to us and of course the endless and endlessly unanswerable questions that come out of that. If you’ve read a lot of noir and detective fiction, you might see a lineage that goes back to the American and English Romantic Movement, to the gothic narratives of writers like Edgar Allen Poe and Mary Shelley, to poets like Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Lord Byron. In a figure like the Byronic Hero, for example—this brooding loner who roams the land, fighting his enemies by himself, hiding great misery in his heart, is full of cynicism and vengeful anger and yet capable of deep and strong affection—this figure is very similar to the detective we are now used to seeing in noir fiction.

And one of the reasons this figure has always been compelling to readers is because he is shrouded in mystery and appears weighed down—fundamentally affected and therefore shaped—by the stories in his past that he is unwilling to tell others, perhaps is unable to tell them.

And this reminds me a lot of the immigrant, of the refugee, of the displaced person in an alien land whose only real possession is his or her memory of their homeland, of the life and identity they were forced to leave behind, perhaps permanently. And while some refugees of course are more than willing to share their stories with people, there are many who refuse to, who cannot do it even if they wanted to, and I’ve always been interested in the reasons why refugees do not tell the stories that they end up carrying around their entire lives here in the new country.

I think that ambiguity—those reasons known and unknown, even to the people who carry those hidden stories—was always the engine for my novel, and if that ambiguity is ultimately meaningful, that meaningfulness comes out of that space between what is concealed or denied and what is unavoidably uncertain and undefined. And if we are to hearken back again to the Romantics, I’d add that this space is marked by apprehension, perhaps even trauma and horror, and therefore moves towards the sublime in that way.

HB: You’ve lived in many different places across the world — Vietnam and Malaysia during your earliest years; Oklahoma, where you grew up; Las Vegas and Iowa, where you studied; and now Chicago, where you teach at the University of Chicago. How do these vast differences in place affect your writing? How has the Midwest affected your writing?

VT: I’ve always thought that my 20 years in Oklahoma has affected my writing the most. I grew up under three layers of insularity: my devout Catholic upbringing, my very traditional and protective Vietnamese upbringing, and the religious and political conservatism of that area of the country. It was not all necessarily negative or even unfortunate, but I think it shaped my need to explore the boundaries of things in my fiction—to write about characters who are restless, itinerant, seeking, empty or disconnected in some way. Las Vegas deepened this exploration for me. My three years in Iowa were hugely formative for me as a craftsman, but my time in Las Vegas was much more personally significant in terms of how that city’s ethos of independence and relative non-judgment allowed me to mature personally. It was in living in Vegas that I found something to say in my writing, and that’s something that no writing program can ever teach you.

HB: As a creative writing teacher, what would you say are the most important aspects of revision? What does the revision process look like for you?

VT: It depends on how you define revision. A lot of writers write a first draft in an automatic and intuitive way, then go back and revise very precisely and carefully. So revision to them is the aftermath of getting everything out, whereupon they shape that mess into something meaningful and beautiful. I revise as I write, on an obsessive level, and cannot move forward until I have things exactly as I want them. I can’t deal with messy. Which is also to say that I write very very slowly. To me, writing is really revising, because I don’t truly know what I’m saying until I rewrite it several times, sometimes twenty or thirty or forty times. I think the only important thing to keep in mind is that revision can be a wonderful and necessary way of discovering your own story, of realizing that the story you started out writing can often transform into something unexpected, entirely different, and even more compelling than you had hoped for.

HB: What’s next for you?

VT: I’m honestly not sure. I’ve considered publishing a collection of stories that I wrote before the novel, but I might have to rethink some of those stories since I’m such a different writer after the novel (and a different person) and would write them very differently now. I also feel like I have the momentum at the moment to write a novel and have thought about one centered around Mai but without any of the other characters from Dragonfish. I also have an idea for another, much different novel, one that’s also working in a specific literary genre, but the idea is too nascent at the moment for me to talk about in any meaningful way. I do like the idea quite a bit.

**

Vu Tran’s first novel, Dragonfish, was recently published by W.W. Norton. He is the winner of a Whiting Award, and his short stories have appeared in many publications, including the O. Henry Prize Stories and the Best American Mystery Stories. Born in Vietnam and raised in Oklahoma, Vu received his MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and his PhD from the Black Mountain Institute at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. He is currently an Assistant Professor of Practice in Creative Writing at the University of Chicago.