Interview: Dan Pope

Midwestern Gothic staffer Giuliana Eggleston talked with author Dan Pope about his new novel Housebreaking, writing with a pad and pen,Iowa Writer’s Workshop, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Giuliana Eggleston talked with author Dan Pope about his new novel Housebreaking, writing with a pad and pen,Iowa Writer’s Workshop, and more.

**

Giuliana Eggleston: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Dane Pope: I’m a northeasterner, from Connecticut. The first time I crossed the Mississippi River by car was in August 2000 when I drove out to attend graduate school at the Iowa Writer’s Workshop. I made the entire trip in one long ride, alone, stopping only for gas. It took 20 hours. I pulled into Iowa City so dazed and exhausted that I was unable to follow the directions I’d scribbled down to the house I’d rented. After a half-hour of driving in circles, I stopped to ask a middle-aged couple for directions. This was my first experience of Iowa politeness, something I was unused to, coming from the northeast. The man patiently explained the directions to me—my destination was nearby—and when he realized I wasn’t following very well, he and his wife said, “We’ll come with you.” And they hopped in the car and brought me there.

Iowa City was one of the best places I ever lived—for the small-town nature of the city, for the kindness and intellect of the people, for the wonderful smell of spring after winter—and I’ve been back many times since leaving the workshop.

GE: What has surprised you most about having a career as a writer? Do you find it to be especially unique from other professions?

DP: Fiction writing makes no sense as a career, in the way most Americans might view the idea of “career.” One does it alone, at odd hours, without any guarantee at all for reward or payment.

What surprises me about of being a writer is how my aesthetic positions keep shifting. I once thought I had a pretty well formed idea of what I aspired to, and liked and disliked in others’ writing. Now I find myself throwing most of those notions out the window. I’ll re-read some story or novel that I read fifteen years ago, and my impressions of the significance of the book will have wholly altered.

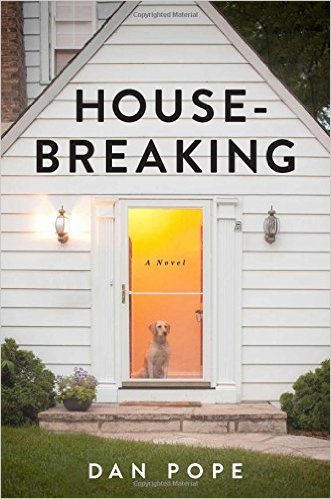

GE: Your new novel, Housebreaking, deals with the disconnect between the perfect illusion and the more than flawed reality of suburban life. What inspired you to delve into this subject? What do you wish to impart to your readers by exploring this subject?

DP: Well, I grew up in the suburbs four or five miles outside of Hartford, so that setting seemed very familiar to me. (My first novel, “In the Cherry Tree” takes place on the same fictional suburban street as “Housebreaking,” and even features some of the same characters.)

When I came back to Hartford after graduate school I started to see my hometown with a different perspective, of course. The suburbs are, inherently, I think, a very strange place, and a relatively recent phenomenon, given that most American suburbs popped up after World War Two, allowing a place for returning veterans to live.

What interests me as a writer about the suburbs is the primacy of appearance and the tension that might cause. (During my teenage years, my mother’s lament, which my brother and I heard over and over upon the revelation of our misdeeds, was, “Oh what will the neighbors think!”) A young man or woman can move to the city and create a new identity, or express his or her inclinations. You can do whatever you like without anyone watching from next-door, and you might even be applauded for it. That’s never been the suburban way. You have to keep up a nice lawn, or the neighbors will get restless. There are secrets and lies, concealments and repression. That’s rich soil for a fiction writer. John O’Hara wrote about that, and so did Cheever and Updike, and I think that dilemma still exists today.

What interests me as a writer about the suburbs is the primacy of appearance and the tension that might cause. (During my teenage years, my mother’s lament, which my brother and I heard over and over upon the revelation of our misdeeds, was, “Oh what will the neighbors think!”) A young man or woman can move to the city and create a new identity, or express his or her inclinations. You can do whatever you like without anyone watching from next-door, and you might even be applauded for it. That’s never been the suburban way. You have to keep up a nice lawn, or the neighbors will get restless. There are secrets and lies, concealments and repression. That’s rich soil for a fiction writer. John O’Hara wrote about that, and so did Cheever and Updike, and I think that dilemma still exists today.

GE: In Housebreaking, you write about a lot of varying characters. How did you get into the mindset of each person? Specifically in the case of Emily, an emotionally distraught teenage girl, how did you go about creating the different facets of her personality?

DP: Some of the characters came easier than others. The older couple, Leonard and Terri, were by far the easiest and most enjoyable to write—easy because they were modeled after friends of my parents and I could still hear those voices from the past quite clearly. I found Emily, the seventeen year old girl, and her history and the different facets of her personality by talking to some female friends and asking what they were like as teenagers—what they cared about, etc. A few themes seemed to recur in their lives. I write in coffee shops a lot of the time, and to update the character to “today,” I asked the baristas what they liked or disliked in pop culture. When I added the very specific tragedy in Emily’s past, her character seemed to take full shape. For some reason, I find it easier as a writer to jump into characters who are much older or younger than me. I don’t think I’ll ever write a memoir for that reason.

GE: Along with writing novels, you have also had a number of short stories published in a variety of journals. Do you prefer one style of writing over the other? Aside from time spent, how does the work put into novels differ from short stories?

DP: When I was seventeen or eighteen, just starting to write, I would produce five- or ten-page short stories. Ten pages seemed long. A decade later, I worked myself up to a fifteen-page story, then twenty pages, etc., until finally transitioning to the long form, and writing a first novel of about 75,000 words at age 39. I think that is the natural progression of most writers. You work up to it, teaching yourself the craft as you go. At one point, back in my early twenties, I had what seemed like unlimited energy but little to write about, given the dearth of lived experience of a person that age. I recall sitting at my desk for hours, trying out ideas, itching to write something, mostly just crossing out sentences. Now, many years later, the opposite is true: limited energy, unlimited material. I have six novels at the moment, in outline form in my head, and at least that many short stories to write too. I plan to tackle the stories first (at least that is today’s plan), because, to answer the last part of that question, I love writing short stories. It seems a luxury to me now, to do so, a sort of holiday from the real work of tackling a new novel. That’s another thing you learn as you progress as a writer, once you’ve written a couple of novels: how much work they take. You think it’ll take X amount of time to write the novel: well, double or triple that. This is because every novel is different, and you have to learn anew how to write each one. It’s like the French and their Maginot Line: hey, this is the way to beat the Germans!, they think. Then the tanks appear and you realize you got it all wrong and you have to start over again from scratch.

GE: What is your writing process like? How do you know when a piece is finished?

DP: I hate sitting in front of a computer. Hate. I don’t own a laptop or mini-laptop or notebook or iPad or any other portable electronic device, including a cell phone. I did, of course, at one time, own a cell phone, but I quickly decided that such gadgets are anathema to creative solitude, not to mention one’s sense of calm. I really don’t know why more people, let alone artists, don’t share this furious dislike of mine. They may purport to dislike the devices, but they don’t get rid of them. They remain in their thrall. I used to find the TV the main distraction and was proud of myself when I rolled the thing out to the garage.

So here’s how I write: with a pad and pen, usually in a quiet place with close proximity to coffee. Then I give those pages to an individual, who types that material into his or her computer for a fee, then emails it to me for corrections, additions, etc., and then I return those scratched up pages to that same person again for more of the same, again, again, and again.

When the coffee shop closes for the evening, I have another, very odd, method of composition. At home, I turn on my piece-of-crap 2005 computer and call up a blank Word file. Then I turn OFF the monitor and take my keyboard (with a 30-foot extension) into the next room. By going into the next room, I can avoid (1) the awful humming of the computer and (2) the spectral appearance of the words on the screen and the concomitant temptation to change or erase said words. Then at some point, maybe an hour later, I’ll go back to the computer and push print and examine the words that spew forth. There will be many misspellings, of course. I’ll mark up those pages and send them off to that same typist for proper word-processing.

You’d think that this would be a huge waste of time, but try it! Try sitting in a room with just a keyboard and your thoughts. I find it to be freeing and fruitful. If I had the screen on, I would be able to see what I was typing, of course, and I would be tempted to mess up a good sentence or paragraph. Instead, I just keep going forward.

Is this weird? I’d be surprised if there is anyone else in the same hemisphere who works this way, with his or her screen off. I’m willing to admit that this is all very strange and ridiculous behavior.

As for knowing when a story or novel is finished, well, I have some ideas on that topic, but I feel like I’ve gone on for too long for question 6 already.

GE: Are there any authors that you feel have had an influence on your writing?

DP: Going back to the start of my scribblings (say, age 12) and proceeding from there in roughly four-year increments: Edgar Allan Poe, Kurt Vonnegut, Ernest Hemingway, John Cheever, Raymond Carver, Don DeLillo, Denis Johnson, James Salter, Alice Munro, Roberto Bolano and Philip Roth.

GE: What’s next for you?

DP: See question 5, above. Of those six novel ideas, I have to choose which one to write, hopefully sometime soon. Two of the ideas are very bad, in that they involve zombies and grotesquerie, but those are the two ideas that appeal to me the most, at this moment. This might be because my last novel, “Housebreaking.” was so firmly placed in a realistic suburban setting, and I find something stranger beckoning.

**

Dan Pope is the author of Housebreaking (Simon & Schuster, 2015) and In the Cherry Tree (Picador USA, 2003). His short stories have appeared in many journals, including Crazyhorse, Harvard Review, Iowa Review, McSweeney’s (No. 4), Shenandoah, Gettysburg Review, and others. He is a 2002 graduate of the Iowa Writer’s Workshop, where he attended on a Truman Capote Fellowship. He is a winner of the Glenn Schaeffer Award from the International Institute of Modern Letters, and grants in fiction from the Connecticut Commission on the Arts.