Interview: Kathryn Harrison

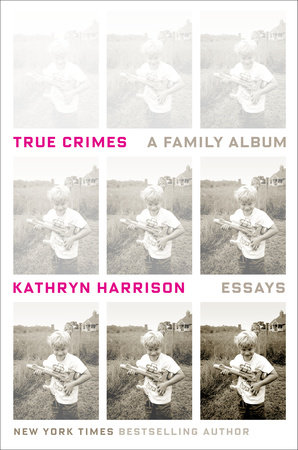

Midwestern Gothic staffer Giuliana Eggleston talked with author Kathryn Harrison about her novel True Crimes: A Family Album, finding meaning in suffering, prose that carries a hidden knife, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Giuliana Eggleston talked with author Kathryn Harrison about her novel True Crimes: A Family Album, finding meaning in suffering, prose that carries a hidden knife, and more.

**

Giuliana Eggleston: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Kathryn Harrison: Short and profound. I lived in Iowa from 1985 to 1987, when I was at the Writer’s Workshop. I met Colin there; we’ve been married more than half my life. As the title essay recounts, Colin and I catapulted ourselves from Iowa City to New York without really thinking. Without a plan.

I flew east to find a place to live; Colin followed with a U-Haul. I had three days to find an apartment whose rent, I discovered, would be three times what we paid for a house in Iowa City. Our editorial jobs, which we were fortunate enough to find relatively quickly, barely covered our expenses and demanded a fifty or sixty-hour week. I wrote between 5 and 7 AM. Life in New York was hard, and exciting. We knew we were going to stay on the East Coast, and we also knew—immediately, I think—that we’d always look back on those years in the Midwest as having a grace we’d left behind.

GE: Your new collection of essays True Crimes: A Family Album, was written over the course of more than ten years. Did you know from the start that you were writing a collection, or did the stories come to you separately with a clear collection forming later? How did you know when the collection was complete?

KH: Assembling Seeking Rapture, a collection of essays written between 1992 and 2002, taught me what I hope makes True Crimes a better book. For that collection, I reviewed all the short pieces I’d written in a decade. Almost without exception, the better essays were driven by my own psychic need to explore something, not conceived in response to an editor’s idea. From that point forward, I wrote only what I couldn’t help writing. Essays that were completely personal, completely me.

By 2014, I had thirteen essays that were thematically united by time: they represent a chapter in a life. After content, the next challenge was to sequence the parts so they came together in a narrative arc. A collection doesn’t have a plot the way a novel does, but I could assemble the parts with the intention of creating conflict, rising tension, crisis, denouement: an emotional arc rather than one formed by plot.

GE: The stories within your new collection are deeply personal, ranging from your own complicated childhood to your experiences as an adult with children of your own. What do you feel are the challenges and rewards of being so emotionally vulnerable with your audience?

KH: It isn’t a challenge to make myself emotionally vulnerable, because I write as the person I am: emotionally vulnerable in any context. In the grocery store or on the subway that’s a liability. At my desk it’s an asset. I intend my work to be a vivisection; I’m the object of my own scalpel and scrutiny and can form a closed circuit that excludes the world, and provides unexpected solace. What might otherwise be exhibitionism reflects an attempt to correct for the life of a solitary.

I can’t speak to the audience’s rewards, but it’s my good fortune to be able use my life as material, and to give its measure of pain meaning. Which is what we all want, isn’t it: to find meaning in suffering?

GE: How has time affected the way you view your “family album”? Are there any stories you wrote that came out differently than you expected?

KH: In as much as I’m always excavating my past, I am always looking forward in terms of my work. Always dissatisfied, focused on growing, evolving. The only reason I reread anything I write is to see how it was I solved a narrative problem similar to the one I’m facing in the moment.

Nothing comes out as I expect, because I’ve never written anything whose ending I could anticipate, nor begun anything with a destination in mind. If I did, I’d be too bored to write it. The novels I’ve outlined are the ones I’ve tossed almost before they were begun. I can’t write a decent essay that isn’t driven by unconscious pressure. True Crime began with my need to understand my addiction to pulpy true crime: what did it mean? Keeping Vigil asks the reader bear witness to the death of my father-in-law. The page offered me the single means I had to pay homage to someone I loved, a person whose death I wanted the reader to mourn with me. At least by the end of the essay.

GE: While often dealing with difficult and dark aspects of life, you are able to infuse your writing with bits of humor and wisdom that reveal different layers of the stories you tell. Why do you think it’s important to include humor and wisdom when dealing with serious topics?

KH: I don’t know how anyone without a sense of humor puts one foot in front of the other. I don’t know any reader who would put up with unleavened difficult-and-dark. And I’m the first among them – the first person I want to amuse is me. Because sometimes I have to laugh at what’s happening to me, on the page if not in the moment.

Wisdom? Whatever I’ve dispensed has been accidental. Very dangerous to go around imparting wisdom.

GE: The honesty you display when writing about your family is bold, coming through with acute clarity to the reader. How do you go about achieving such candidness in your writing, and why was casting light onto dark aspects of life essential to your collection?

KH: It isn’t achieved; it’s helpless. There are a lot of people who would prefer I were neither bold nor acute, readers who don’t want a book that’s honest about what they’d rather not consider.

For them, there is another, more demure, writer. Me: I want to get to the point. I want prose that carries a hidden knife. I want to cut you before you know I have.

GE: Aside from memoirs, you have also written novels, personal essays, two biographies, and a work of true crime. How do your processes vary for each type of work, and do you have a preferred type of literature to write?

KH: Fiction grants the freedom of invention: whatever I can imagine I can use. And with the exception of The Seal Wife, that freedom encourages me to be more playful with language, and with events. One of the characters in Enchantments is a depressive who lives her life “under a cloud.” A literal one that follows her and reflects her moods. Non-fiction—whether biography, memoir, or true crime—comes with a plot that can’t be manipulated to suit my intentions. It demands my being willing to discover what may change the shape of the book or destroy my assumptions, often about myself.

I tend alternate because the forms demand such different approaches that going back and forth between them prevents fatigue. My short work is occasional and interrupts my writing a book—something unfolds, either without or within me and demands immediate attention. I never plan to take breaks from a work-in-progress, but it’s good to be forced to do so.

GE: What’s next for you?

KH: I’m working on a memoir called Sunset. I grew up on Sunset Boulevard under the care of my maternal grandparents, who were born in the 1890s and whose stories of their far-flung improbably lives—and their readiness to tell them— provided a perfect petri dish for a baby writer. Especially when added to an atmosphere so bizarre as to have been judged “surreal” by reviewers. The first time I encountered that observation I felt a little defensive. But there was a reason I never invited other children over to play.

I heard it all my life: your grandparents are such interesting people; how lucky you are to have them. They were, and I was, and now it’s time to pull my grandfather into the light, and convince my scene-stealing grandmother to move over a bit.

**

Kathryn Harrison has written the novels Thicker Than Water, Exposure, Poison, The Binding Chair, The Seal Wife, Envy and Enchantments. Her autobiographical work includes The Kiss, Seeking Rapture, The Road to Santiago, and The Mother Knot. She is also the author of a book of true crime, While They Slept: An Inquiry Into the Murder of a Family, and the author of the biographies St. Therese of Lisieux and, most recently, Joan of Arc: A Life Transfigured. She lives in Brooklyn with her husband, the novelist Colin Harrison, and their three children.