Interview: Dan Barry

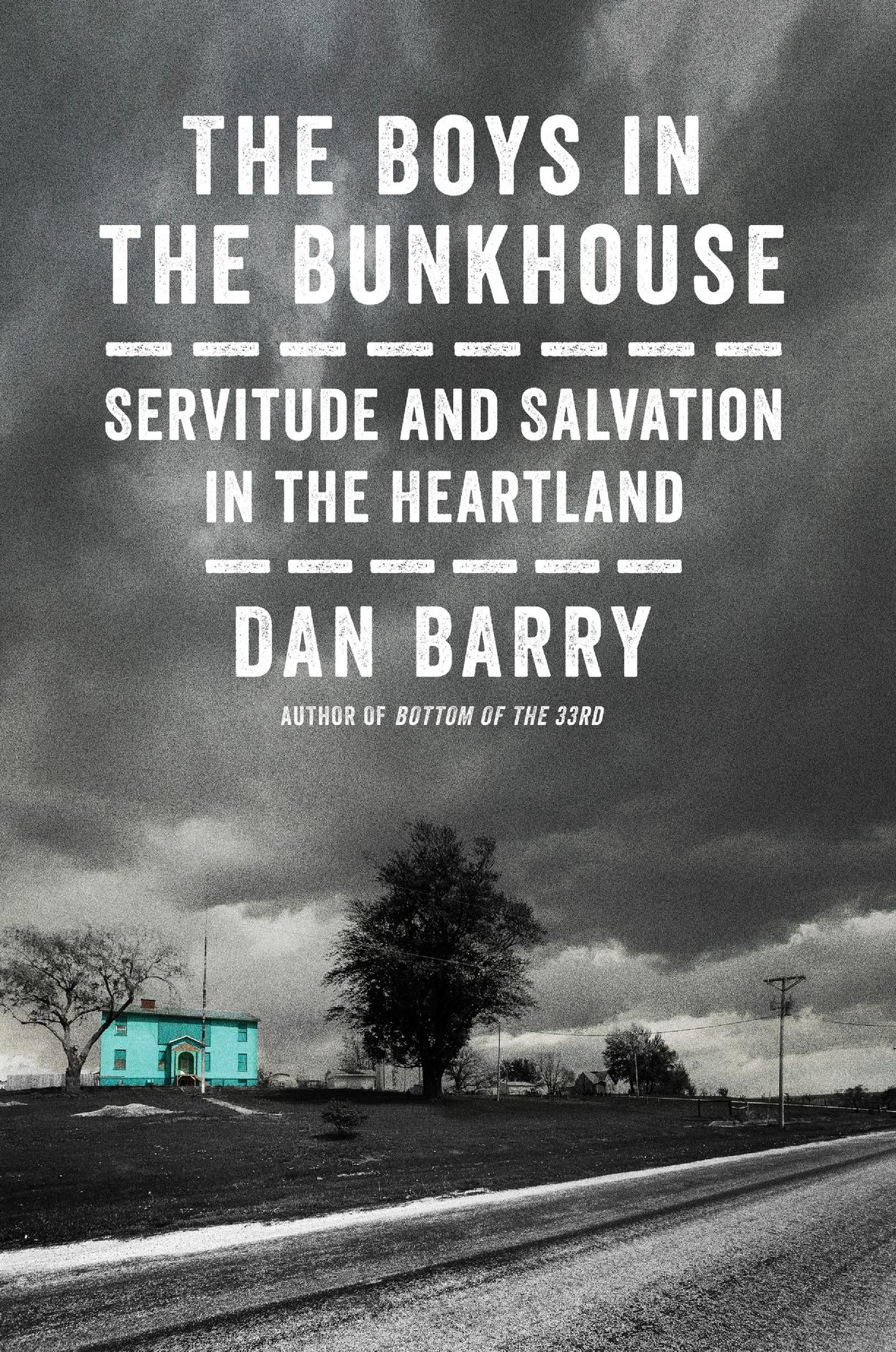

Midwestern Gothic staffer Sydney Cohen talked with author Dan Barry about his book The Boys in the Bunkhouse, giving voice to the voiceless, corroborating stories from the mentally disabled, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Sydney Cohen talked with author Dan Barry about his book The Boys in the Bunkhouse, giving voice to the voiceless, corroborating stories from the mentally disabled, and more.

**

Sydney Cohen: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Dan Barry: I have no familial or work-related connection to the Midwest. I guess the connection would be through the stories I’ve found there through the years, especially as a roving columnist for The New York Times. I can’t count how many columns I’ve written from there: a reunion of retired burlesque performers in Baraboo, Wis.; the attack of crows upon the fair city of Terre Haute, Ind.; the tornado in Joplin, Mo.; the gravesite of Sitting Bull in Mobridge, S.D.… Some of my biggest projects have been in the Midwest: Donna’s Diner in Elyria, Oh.; a boxing story rooted in Dearborn, Mich., and Youngstown, Oh. And, I guess, The Boys in the Bunkhouse, in Iowa. I guess I just like the Midwest.

SC: Your new book, The Boys in the Bunkhouse, is a harrowing tale of the marginalization and abuse of the mentally disabled men from Texas. Your past work, including your New York Times column “This Land,” also deals with the theme of uncovering exploitation in hidden corners across the United States. What inspires you to write about “the other” – the figures drifting on the margins of society?

DB: As a storyteller, I am craven: If it’s a good story – funny or sad, about the rich or the poor – I want to tell it. But at the same time I am drawn to those stories in which the voiceless can be given voice. Their stories perhaps have not been heard before, or have been drowned out by the everyday cacophony. My father was a Depression kid who had it tough in New York City; my mother was born in Ireland and orphaned by the age of 15. I think they instilled in me the sense that everyone matters; everyone has something to say. And that maybe, through the telling, some justice can be found – or, at least, some deeper understanding.

SC: The Boys in the Bunkhouse tells a starkly true story of the exploitation of dozens of mentally disabled men at the hands of one corrupt overseer, who kept these men in squalor and servitude for decades. You tell this story through literary and poetic prose, a style of writing that forms the genre of literary nonfiction. What is important to keep in mind when crafting a literary nonfiction narrative?

DB: I just had this conversation with a friend of mine, the great novelist Colum McCann – about that pursuit of truth. But he’s a novelist, and I’m a journalist. For me, what’s important in literary nonfiction is that everything is both factual and contextually accurate – and then the writer brings flesh and blood to it. You do this by vacuuming up the details that put the reader in the moment, by interviewing the subjects so exhaustively that you know what they were thinking at a given moment, and by putting it all together in a novelistic way. And then you call those subjects to make damned sure that your facts and context are true; that you have not followed your muse down a path that leads away from truth, simply because it sounds prettier.

SC: What was the most challenging aspect of your work writing The Boys in the Bunkhouse, from the idea’s conception to the book’s publication?

DB: I suppose it was in trying to understand the entire sweeps of the lives of these men, which at times was difficult because their intellectual disability often means that their sense of time’s passage is off. If I asked Willie Levi, for example, when he first came to Iowa, he might say last year – when, in fact, it was 35 years ago. These men all grew up in state institutions in Texas, many were effectively abandoned by their families, and now here they were, in Iowa. My central challenge was to corroborate their stories through repeated interviews, long visits, traveling to Texas, and poring over court documents. In the end, I learned that if Willie Levi said something happened – it happened.

SC: How has the tale of the Iowa bunkhouse, and the events that took place there, impacted or influenced your thoughts and feelings about the Midwest?

DB: I would say it hasn’t changed my affection for the Midwest in any way. I see Atalissa, Iowa, as a microcosm of all of America. Every American place is capable of negligence, of cruelty, of being blind to the quiet suffering of the vulnerable around us – just as every American place is capable of great humanitarian warmth and kindness and heroism. The men experienced all this in Iowa.

SC: Throughout your career, you have reported on an extensive and impressive amount of major American events. What story did you find the most eye-opening and impactful (if you could pick just one), and what about that story was most poignant?

DB: I am a New Yorker, and it is hard to get past the events of Sept. 11th. That day, and the year or so I spent covering its aftermath, has probably had more of an impact on me than any other story. How could it otherwise? There are so many parts of that tragedy that stay with me: the Staten Island landfill, where investigators pored over the debris for human remains and personal effects; the medical examiner’s office, where workers tried to identify an arm, or a foot, so that families could have a piece of a loved one to bury…I could go on. What sticks in my mind most is a story I wrote about the vanilla-colored dust that settled on many of the buildings in Lower Manhattan after the twinned collapse. People used their fingers to write prayers and pleas and goodbyes to loved ones, knowing full well that it was ephemeral; that soon it would be power-washed away. But it hasn’t for me and, I bet, for so many others.

SC: As both a journalist and an author, how do you navigate between the contrasting platforms of articles versus books? With The Boys in the Bunkhouse in particular, how did the story change from its original space on “The Land” to its recent book form?

DB: The original “This Land” column that appeared in The New York Times in March 2014 was several thousand words, although my initial draft was twice that. After the column ran, I had so much more to tell – so many more anecdotes and revealing moments – that I pitched the notion of a book, and, thankfully, HarperCollins agreed. I then did a lot more reporting before sitting down to write. One way that the book was different was in setting it up almost as a thriller: a social worker on duty at night gets a call from an anonymous tipster (a bunch of men with intellectual disability…working in a plant eviscerating turkeys…living in squalor…getting paid nearly nothing…) Another way was to begin with a prologue that gave one of the men voice, telling his story quickly so that the reader realizes what was at stake, and what was lost. The book allowed the men – and me – to breathe more.

SC: What’s next for you?

DB: I honestly don’t know. I think I’ll be writing the “This Land” column through this singular election year. Then after that, I guess, just find another story.

**

Dan Barry is a longtime columnist and reporter for the New York Times, and the author of four books, including the forthcoming The Boys in the Bunkhouse: Servitude and Salvation in the Heartland. His other books include a memoir, a collection of columns, and Bottom of the 33rd: Hope, Redemption, and Baseball’s Longest Game, which won the 2012 PEN/ESPN award for literary sports writing. Barry has reported on many news events for the Times, including the attack on the World Trade Center and the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. He has been a City Hall bureau chief, a Long Island bureau chief, a sportswriter, a general assignment reporter, and, for three years, the “About New York” columnist. As the “This Land” columnist for the Times, he traveled to all 50 states, where he met the coroner from “The Wizard of Oz” in a Florida retirement home, was hit in the chest by an Asian carp leaping out of the Illinois River, and learned the bump-and-grind from a retired burlesque queen in Baraboo, Wis. Barry previously worked for the Journal Inquirer in Manchester, Conn., and for The Providence Journal, where he was part of an investigative team that won a Pulitzer Prize in 1994 for a series of articles about Rhode Island’s court system. Barry has received many other honors, including a George Polk Award; an American Society of Newspaper Editors Award for deadline reporting, for coverage of the first anniversary of Sept. 11; a Mike Berger Award for in-depth human interest reporting; an award for column writing from Sigma Delta Chi/Society of Professional Journalists; and the Best American Newspaper Narrative Award. He has also been a nominated finalist for the Pulitzer Prize twice: in 2006 for his slice-of-life reports from hurricane-battered New Orleans and from New York, and in 2010 for his coverage of the Great Recession’s effects on the lives and relationships of America. Putting all this in proper perspective was a fifth-place award for feature writing from the American Bowling Congress that misspelled his name. Barry lives in Maplewood, N.J., with his wife, Mary Trinity, ’81, and daughters, Nora and Grace.