Interview: Amy Hassinger

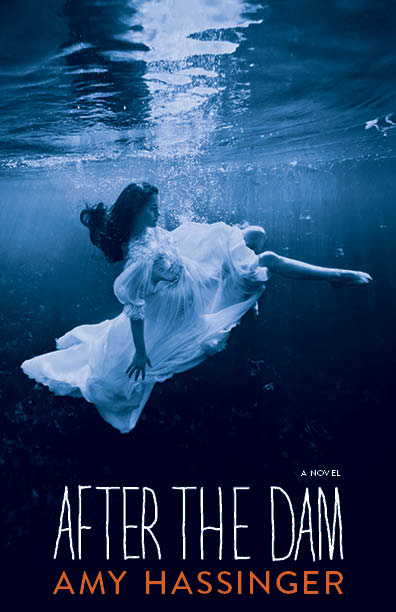

Midwestern Gothic staffer Megan Valley talked with author Amy Hassinger about her book After the Dam, learning through teaching, commonalities between environment and motherhood & more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Megan Valley talked with author Amy Hassinger about her book After the Dam, learning through teaching, commonalities between environment and motherhood & more.

**

Megan Valley: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Amy Hassinger: I’ve lived in the Midwest since 1999, when I moved to Ames, Iowa from the east coast. Since then, I’ve lived in Ames and Iowa City, Iowa, Okemos, Michigan, and Urbana, Illinois, where I live now. But my roots go deeper: my mother was raised outside of Chicago, and my family has vacationed on a lake in northern Wisconsin going back four generations.

MV: After the Dam is your third novel — how has your approach to writing changed since Nina: Adolescence was published in 2003?

AH: For one thing, my time has grown more fragmented as I’ve taken on more responsibilities (becoming a mother, taking on teaching jobs, editing others’ work, promoting my own). I like to think I’m more efficient with the time I do have, though that’s not always true. My process remains similar. I like to plunge into research on almost any piece I’m working on. I want to get out of my own narrow range of experience and expand the boundaries of self and voice. So I do a lot of reading, lurking in libraries, and web-trawling for an inordinate length of time. Also, talking to people who know something about the world I’m learning about. If it’s a place that’s new to me, I visit it, do my sensory research — taking in the light, the lay of the land, the smells, impressions. And then I’ll dive into the vicissitudes of the drafting process. The research is essential for me — it introduces me to the raw material of my story.

MV: How have your experience as a Faculty Mentor in the University of Nebraska at Omaha’s MFA in Writing Program, teaching at the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute, and a writing workshop leader influenced your own writing?

AH: Teaching has helped me articulate and put names to the things I was doing on a more unconscious level in my own work. I understand the mechanisms of story structure more thoroughly now for having taught them. Workshops require close reading of others’ work, which is always instructive. Having to prepare lectures regularly provides me with a structure within which to explore questions that might be bedeviling me in my own work. So, for example, if I’m having trouble figuring out how to whittle down and otherwise grapple with the enormous amount of exposition I need to fit in my own novel (as a result of all that research!), I’ll take a look at how other writers have handled it, and compile my observations into a lecture. To teach well, you must always be learning. The same is true of writing.

MV: After the Dam was a finalist for the Siskiyou Prize in New Environmental Literature. How do environmental themes fit together with the other major theme of motherhood?

AH: As the title implies, there is a dam at the center of the novel. This dam is both a literal story element — a physical structure that holds back water — and a symbol, a literary structural element. In the book, the construction of the dam transformed its surroundings, causing both ecological damage and social trauma to the local Ojibwe tribe, whose land, ricing grounds, and ancient graves were flooded to create the reservoir. The novel explores both the legacy of this dam as well as its future, and the future of the river it controls.

Motherhood, too, is a kind of radical, even violent transformation. In the novel, Rachel, the protagonist, resists her new identity and its domestic expectations, even as she fiercely loves her baby. She has to be willing to let go of — even destroy — her former pre-mother self in order to embrace the unfolding reality of who she is becoming.

MV: The main characters of your three novels include: a young woman enamored with a priest near the turn of the century in France, a fifteen-year-old girl who becomes a model for her artist mother after the death of her brother, and a young mother who runs away from her husband. How do you create such varied characters and voices?

AH: I guess it goes back to research. As I mentioned earlier, I really am interested in pushing at the boundaries of my own experience. Maybe it’s because I find my own life relatively conventional, maybe it’s because I’m a curious person, maybe it’s because I’m restless and always looking for the next challenge, but a large part of the reason I write (and read) is because I want to explore. Hence the varied subject matter. Of course, the challenge then becomes learning enough about your material to write about it convincingly and well, in other words, getting the details right. That’s the tricky part.

MV: What do you read when you’re not working on your own writing or as a manuscript consultant? How have these affected your writing?

AH: I’m a relatively haphazard reader, a thing I’m always vaguely wanting to change about myself, but never quite getting around to doing. Often I’m reading something that has to do with my work. I produce a weekly micro-podcast called The Literary Life that features the work of Midwestern authors, so I’m always looking for writers to feature. Writers I adore and return to include Virginia Woolf, Louise Erdrich, Andre Dubus, PattiAnn Rogers, Toni Morrison, Aleksander Hemon, Marilynne Robinson, and Gustave Flaubert. Writers I adore and want to read more of include Alice Munro, Kevin Brockmeier, E.L. Doctorow, Rebecca Solnit, Jeffrey Eugenides, Eowyn Ivey, Haruki Murakami, Colm Toibin, Mary Oliver. The list goes on and on!

Each of the writers I’ve read and loved has influenced my work in some way, I’m sure. Virginia Woolf’s Orlando took my breath away and made me want to be a writer when I first read it in college. I still strive (and fail) to plumb the psyches of my characters as deeply as she does. I read Andre Dubus for his depth of compassion, another thing I strive for in my own work. I love Louise Erdrich’s expansive stories and flexibility with point of view. PattiAnn Rogers’ poems are joyous songs of praise and awe at the intricately evolved organisms all around us. Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon gave me one of my first lessons in novel structure, and her willingness to entertain the magical opened up the possibility of what could be done in a novel. Reading Aleksander Hemon’s sentences is like excavating gems — each one a discovery. Marilynne Robinson’s novels are gorgeous prolonged meditations on spirit and existence; Flaubert’s Madame Bovary is a model of evocative descriptive writing. Each of these people, along with many many others, has taught me something essential about how to write a sentence, a paragraph, a story, a book.

I just finished re-reading Richard Hoffman’s memoir, Love & Fury. All the way through, I found myself admiring his craft — the way he weaves together several different storylines as well as his own essayistic reflections on fatherhood, boyhood, and grandfatherhood, as well as race and class in America. After I set it aside, I immediately was hit with three new ideas of pieces or books I wanted to write. Somehow, reading his book and admiring his craft opened that door for me. Reading is an absolutely essential part of the process, beginning, middle, and end.

MV: What do you wish you had known when you first began writing?

AH: Well, I’m certainly glad I didn’t know how difficult it would be to complete a project, let alone make a living as a writer. Entering it naively was probably the only way for me to do it. I didn’t know better. If I had, I never would have done it.

I don’t think there’s anything I could have known back then that would have smoothed the way. It’s not a smooth way.

MV: What’s next for you?

AH: I’m sitting on a draft of a new novel right now, letting it cool. I’ve got an essay I’m working on about a back infection that almost killed me two years ago, and a couple other short pieces waiting in the wings. After that, I plan to tackle one of several longer-term projects I have in mind. We’ll see what pulls me.

**

Amy Hassinger is the author of three novels: Nina: Adolescence, The Priest’s Madonna, and After the Dam, a finalist for the Siskiyou Prize for New Environmental Literature. Her writing has been translated into five languages and has won awards from Creative Nonfiction, Publisher’s Weekly, and the Illinois Arts Council. She’s placed her work in numerous venues, including The New York Times, Creative Nonfiction, The Writers’ Chronicle, and The Los Angeles Review of Books. She is a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and teaches in the University of Nebraska at Omaha’s MFA in Writing Program. She also produces a micro-podcast called The Literary Life that features the work of Midwestern writers. You can find out more about her at www.amyhassinger.com.