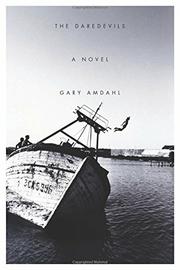

Interview: Gary Amdahl

Midwestern Gothic staffer Megan Valley talked with author Gary Amdahl about The Daredevils, musing vs. building, radical labor activism and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Megan Valley talked with author Gary Amdahl about The Daredevils, musing vs. building, radical labor activism and more.

**

Want to get your hands on a copy of The Daredevils? We’re giving away three copies of the book — find any of our posts about the giveaway on Twitter and retweet to be entered to win. Only one book will be awarded per person, but feel free to RT as many times as you want to get multiple entries! Deadline is Sunday, 11/20 at midnight. US only please.

**

Megan Valley: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Gary Amdahl: I was born in Jackson, Minnesota, on a farm with no running water, in 1956. My mother was born there in 1935, and carried water from well to house every day of her life until she left for college. Her father was born near there in 1890. His father was born near Mankato in 1857. Legend has it he saw the mass hanging of thirty-eight Dakota men in retaliation for the Sioux Uprising of 1862. They were from around Hallingdal, Norway. On my father’s side, my great-grandfather came from near Stavanger, Norway and settled in northeastern Iowa. I graduated from Robbinsdale High School in 1974 and took twelve years to get a B- English BA from the University of Minnesota, at which point I departed the Midwest for good (coming back only for my last play and to get married on Madeline Island in Lake Superior).

MV: You’ve written six books and nine plays; what’s the difference in writing those two types of literature?

GA: That’s a good question, and one I never get tired of thinking about. For starters, in a novel, I think, you can muse, whereas in a play you have to build. In a play, every line has to answer a question for the audience, and ask another one. There’s no time to lose. The audience has to be waiting for the next entrance, but the entrance, when it comes, has to be a surprise. I’m not talking about melodramatic contrivance — although a playwright can have a lot of fun, do a lot of good work with such silliness — I’m talking about actually constructing something with words and gestures that the audience can see taking shape before their eyes, something that holds together but which can’t be predicted. So it’s not quite carpentry and it’s not quite card tricks.

MV: The Daredevils centers on a man who obsesses between performance and “real” life — how does this relate to the political themes, including radical labor activism?

GA: Wow. Thank you for asking the only question that mattered to me in the end. (Writing The Daredevils took a very long time; please see http://www.necessaryfiction.com/blog/ResearchNotesTheDaredevils for the story of the story.) Hundreds of great books have been written on this subject, from Erving Goffman’s The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life to Galen Strawson’s Selves, and every major philosopher and sociologist deals with it one way or another; novelists have long played with the alternation of aspects of “the personalities of characters” as they change perforce or by calculation from situation to situation.

So I have this tremendous intellectual and artistic foundation, but I am mainly dealing with personal experience. I was outgoing as a kid, a budding decathlete, socially active and socio-politically adept — if a grade- and middle-schooler can be said to be such a thing, and I think he can — but became other-end-of-the-spectrum shy, and spent my twenties in alcoholic, suicidal despair. But because I was also in the theater, and hanging around with people who didn’t philosophize about acting, but instead simply acted, for better or worse, in sickness and in health, I somehow began to see that there was no self worth speaking of without action, and that if I thought too long about anything, I’d never ever act. My life would be the wholly interior life of the alcoholic. Mental health would become something I couldn’t take for granted. So I began to act in what seemed to me to be desperate, goofy, reckless ways. But to other people, apparently, I seemed to be coming to life.

Long story short: politics is a particularly desperate and goofy and reckless kind of action that affects everybody on the planet willy-nilly. It is also particularly visible, often brazenly and ridiculously so. The actions often seem cowardly or calculated, rather than genuine and brave, which was how I wanted to perceive my own “personal political actions.” The difference between what I came to think of as my personal radicalism and a larger more inclusive political radicalism was just a matter of venue and connection. The difference between radical politics and mainstream/center politics is the same as the difference between an actor and a member of the audience. “Radicalism” isn’t associated with “activism” for nothing (not that they are the same thing — they aren’t). There is a great deal of pressure on all of us to do nothing. And I am generally a proponent of that Pascalian proposition that evil flows from people who are not content to sit quietly in their rooms. But: we are simply not capable of sitting in our rooms quietly forever. I meditate, and I know some Big Meditators: we all agree that you can’t do it for very long, and if you press it, you get weird. There’s a difference between letting it be and not caring, between apathy and disinterest. We have to act because we have bodies. We’ve got great opportunities to go with the flow, to be passive spectators, both of light entertainment (TV, movies, etc.) and heavy entertainment (politics), but in the end, our physicality forces us to act.

Ideally, I can act simply and surely, with a cool head and clean hands so to speak, in a spirit of constant improvisation as the present happens and my brain lets me know that means to me — but only if I improvise. Calculation is forbidden, and much, much worse is expectation of success, expectation of anything, really. If you start depending on and calculating for and expecting success…you are doomed. Wickedness and misfortune can ensue just as naturally as riches and fame. You start to buy into…wait for it…the narrative, and the narrative starts to direct the action rather than the action directing the narrative. A subtle difference, perhaps, but a fundamentally important one. Cool improvisation will always be seen as radical in a passive environment devoted to maintenance of the status quo, even if the status quo isn’t particularly comfortable or desirable; but somewhat paradoxically, cool improvisatory radicalism is always the way to restore comfort to a tormented soul, family, city, country, world. (For example, I’m hard pressed to think of a more radical outfit than Alcoholics Anonymous.)

I say this as a human being whose illusory self is composed of nothing but competing narratives offered up by the people of his time and place — here’s how to succeed, here’s how to be happy, etc. — but also as a dramatist and a novelist. Stanislavsky’s major question was something like “Does the emotion elicit the act or does the act elicit the emotion?” The answer isn’t simple, but it was clear from the start that the actor had to get up on the stage and move before anything else could happen. I’m not a postmodernist (I think most artists reject categories like that, even “artist” when you get right down to it) but I do despise tired conventions, and I have a special dislike for the infantile melodramas that currently dominate our literary narratives. The two main characters in The Daredevils, Charles Minot and Vera Kolessina, are poised just on either side of the line that divides improvisation and narration. Vera, a poor mill girl, has quite a story of success already behind her, and is inclined to want her improvisations to continue to propel her forward toward greater success. And who could blame her? Charles is fantastically wealthy. We have seen countless upper-class twits disgusted by their inherited fortunes, and countless more devoted to them, but I don’t think we’ve seen many who are radically disinterested in them.

MV: Which writers have most influenced your style?

GA: Style, as opposed to inspiration, and including method: James, Proust, Faulkner, Halldór Laxness, Malcolm Lowry, Patrick White, Pynchon.

MV: In your novel, Charles Minot starts in San Francisco and relocates to the Midwest. What role does setting play in The Daredevils?

GA: I wanted the novel to open with that feeling that San Francisco still has, of vast wealth and land’s-end bohemianism, the Golden West and the corruption, opera and motorcycles, mild climate and wild desires — and then show how ephemeral or indeed illusory it all is. The move to Minnesota was inspired by my growing awareness that nice little Minneapolis was a seat of power every bit as corrupt and wealthy as San Francisco — and they had a Socialist mayor in the middle of it all! Minneapolis was Big Timber, Big Iron, Big Grain in the way that San Francisco is now Silicon Valley. And the state and the Twin Cities were run by men who would have loved to have a clown like Donald Trump as their public face.

MV: What do you wish you had known before you began writing?

GA: I wish I had known that it was more important, and healthier for both body and soul, to write what I could write, and not worry about what I couldn’t write.

MV: As someone’s who written many plays, how did that influence your writing of The Daredevils, which focuses on the themes of performance and theatricality?

GA: I answered this over-thoroughly above, so I’ll just add this: I wanted to say everything about the theater and acting in the novel that I couldn’t say or do in a play. Now of course I wonder how I might adapt the novel to the stage…

MV: What’s the best piece of advice you’ve ever gotten on writing?

GA: This is going to sound arrogant or weird, but…I’ve never gotten a piece of advice on writing. Unless it’s the bromide my near and dear ones have kept handy for decades: don’t let the assholes get you down.

MV: What’s next for you?

GA: The Daredevils sold very poorly, so I am looking for a new publisher. I have three books ready to go: a short novel told entirely in dialogue, Three Clowns, Or, Bellus Spectaculum Gazebo: A Transcript of a Midsummer Night’s Dialogue in Three Acts Concerning the Supreme Fiction; a collection of essays, stories, and poems; and a long novel, The Treaties. I am also looking for a theater to produce the first play I’ve written since 1989: Dharma Comes to Dinner.

**

Gary Amdahl‘s most recent works is a collection of stories, The Intimidator Still Lives In Our Hearts (Artistically Declined Press 2013); two novels, Across My Big Brass Bed (ADP 2014) and The Daredevils (Soft Skull 2016); an essay, Much Ado About Everything: Oration on the Dignity of the Novelist (Massachusetts Review Working Title, 2016), and a play, Dharma Comes to Dinner. He lives in a cracked and dusty test tube filled with fifteen million people that lies between Los Angeles and Palm Springs, with his wife, PEN award-winning writer Leslie Brody, and their dog and cat.