Interview: Steve Yates

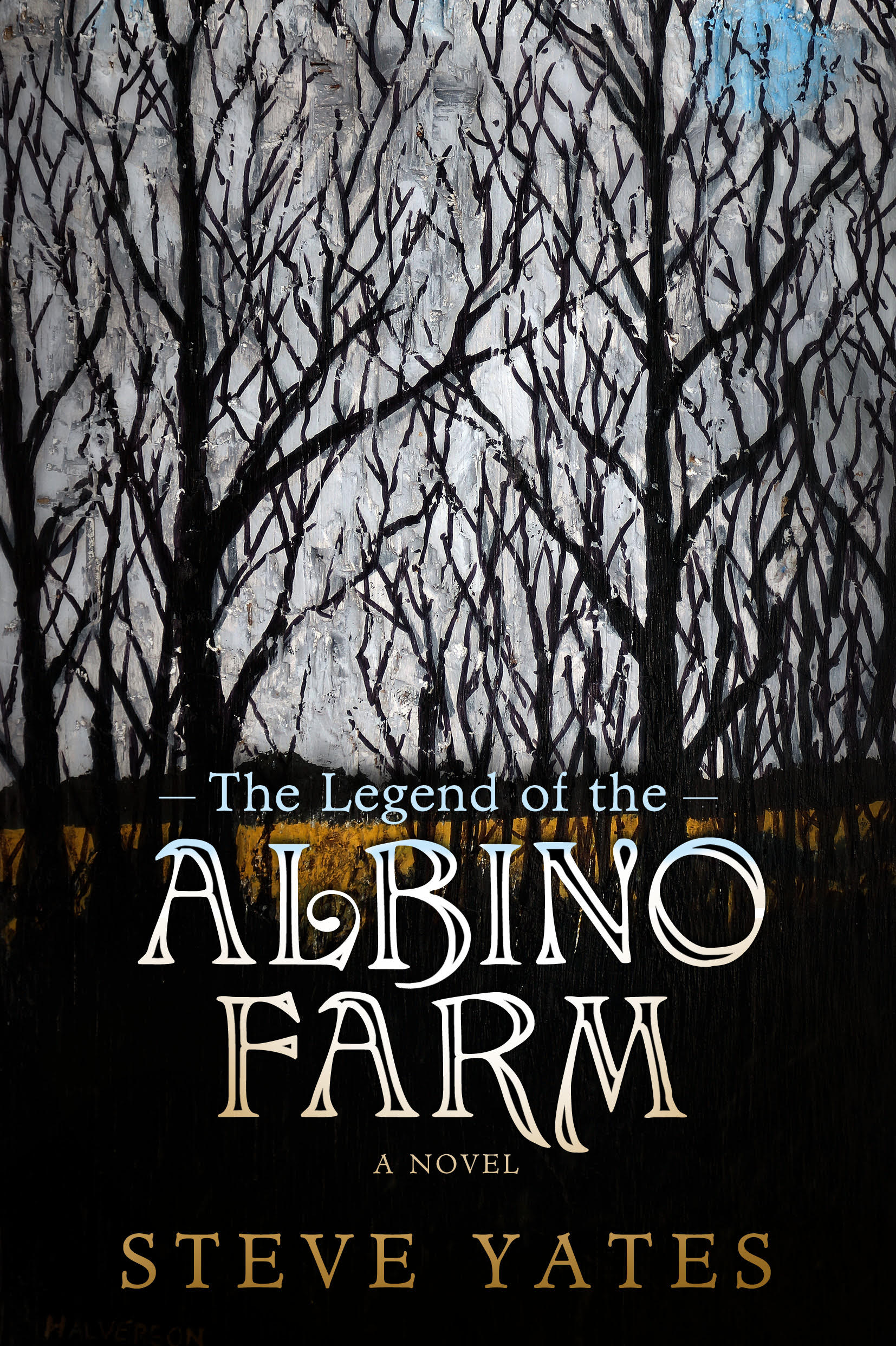

Midwestern Gothic staffer Audrey Meyers talked with author Steve Yates about his book The Legend of the Albino Farm, the dangerous implications of legend, telling a horror story inside-out, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Audrey Meyers talked with author Steve Yates about his book The Legend of the Albino Farm, the dangerous implications of legend, telling a horror story inside-out, and more.

**

Audrey Meyers: What is your connection to the Midwest?

Steve Yates: I was born and reared in Springfield in the Missouri Ozarks, that hilly borderland between the Midwest and the Upland South. Two counties separate my hometown from the Arkansas line. It is the largest city and chief mercantile hub of the region. On a high plateau before the White River Hills begin, Springfield has long been the last market crossroads where provisions from Chicago, St. Louis, and Kansas City could be found. South of town the adventurer descends into a wilderness as oaken and beautiful as it is flinty and perilous. Springfield, Queen City of the Ozarks, lit the stage for Porter Wagoner and gave Bob Barker his start in radio. While with us, Brad Pitt learned to fire pistols and play tennis. We educated the mighty John Goodman and the luscious Kathleen Turner. We are the genius homogenizers who gave you Bass Pro Shops, O’Reilly Automotive, and the first Sam’s Club. You don’t know us, but we sell you everything.

AM: How has the Midwest influenced your writing?

SY: I am the grandson of a St. Louis bank president and a Dallas County tenant farmer. Those worlds, four hours separated by car, are as far apart as the proving grounds at Lockheed Martin and the limestone chasms of Smallin Cavern. My ancestry combines English, French, German, Irish, Scots Irish, Scottish, and (according to family lore) Blackfoot. Maybe that mad mess opens me to writing from multiple strains. I’m a fiercely loyal fanatic for Daniel Woodrell and Donald Harington, the Tom Sauk and Mount Magazine of Ozarks letters. But I am most often rereading Joseph Roth, Henry Green, Alice Munro, Herman Melville, and Anton Chekhov. The Ozarks was and still is a place where the Midwesterner, in dire straits, can vanish into forbidding hills and shadowy hollows, then emerge resolved with a steeled (if not stolen) identity. I think, sometimes, my writing is that — each novel, novella, or story a plunge into a borderland wilderness hoping to forge something new.

AM: What inspired you to write your latest book, The Legend of the Albino Farm?

SY: This may sound cold and analytical, but this is how I came to it. In 2013, I was casting about for what to write next. In my two published novels, Morkan’s Quarry and its sequel, The Teeth of the Souls, I felt I had treated the two cataclysms in Springfield’s history — our Civil War and the 1906 Easter Lynching. In Some Kinds of Love: Stories, I had tackled the Ether Eddie case and several other Springfield incidents. In Sandy and Wayne: A Novella, I managed to tell a love story about the building of an interstate through the Ozarks. What next? The strange old muddle of The Albino Farm, a legendary haunt north of town, came to mind. Researching, I found a 2006 column by a trusted journalist I had worked with at the Springfield News-Leader. In her column, Sarah Overstreet attempted to track what was behind our town’s bizarre tale of a vicious albino caretaker, or a sequestered colony of tortured albinos. A distant relation to the wealthy, prominent Irish Catholic family that had actually lived on this farm refused the chance to speak with her. He was too upset that this nonsensical legend had so long obscured the glory of a golden family and a home place he believed was paradise. Decades after vandals had burned the twelve-room mansion to the ground, he remained too distressed to set the record straight. He had given up on telling his truth. I was all in.

AM: When and how did you first hear about the Albino Farm?

SY: Freshman year at Greenwood Laboratory School, the instant a friend secured a car, a Missouri driver’s license, and a bottle of Cosca Bolla red wine. My friend, Eric Anderson, gravitated to supernatural lore and adventure. We were inventively and criminally irresponsible. Journey, Story, Thrills, and Music meant everything.

AM: What was your immediate reaction and how did this lead to writing your book?

SY: I think even then, to Eric’s great annoyance, I did not understand and vehemently questioned what was so frightening or supernatural about the place. There was to me nothing threatening or magical about persons who happen to have the genetic difference of albinism. I knew quite a lot about the difference, back then considered an affliction — I was an obsessive child, and any human distress compelled me to hours upon hours in the Brentwood Public Library. If you live with a hometown legend that horrifies by making a monster of someone who is not monstrous at all, how could you avoid as a writer trying to deal that legend a death blow?

AM: What genre do you think The Legend of the Albino Farm most closely belongs to?

SY: Family saga. It’s a horror story told inside out. The family’s problem, the family’s affliction is that their home place and farm have acquired a nonsensical legend that unleashes a torrent of thrill seekers, drunks, druggies, vandals, bikers, and Goths. The Sheehys of Emerald Park—a family I invented but based closely on the Sheedys of Springlawn Farm—are just a large, thriving Irish Catholic family in the Ozarks, and there are no albinos among them. Yet, subjected to this cursed legend, their lives transform from idyll to hell in just a decade.

AM: Were there any difficulties or problems while researching this topic?

SY: Astonishingly none whatsoever. Every time I conceive a story about Springfield or the Ozarks, I’m terrified someone else will write and publish that fiction before I do. With the publication of this one, I am five-for-five, a streak too lucky to continue. The story of the family that actually lived, loved, and thrived on the farm is well documented in newspaper archives at the Springfield-Greene County Library Center. At the Greene County Archives, the family’s copious, meticulous wills detail their rise and fall into decrepitude and oblivion almost as completely as would a videographer. Death Notices, Tax Records, Deeds of Trust, even a commissioned Historical Survey — all so simple to access. The intensive research really took but a blizzardy fortnight in December, and photocopying fees. And I should add a lot of talking with my father, a lawyer, and father-in-law, descendant of a farming family.

AM: What did you learn from your research process?

SY: Never assume. Let the money speak. Don’t read the abstracts; read the letters. The story is always sadder, stranger, and more beautiful than you imagined. The drama waits not in what we obtain, but in when we abstain. Obsession with property is a powerful curse. Get your own Will in order. Everything is narrative.

AM: How do you believe a story should be told? In other words, do you follow a guideline for telling a story?

SY: To me, every story is different, different in voice, in ambition, in scope, different in the consciousness and the universe it creates. The living characters will show you how to tell the story. That said, researching this novel afforded me valleys and summits, horrors and triumphs along the timeline of a family’s reign. So in many ways I had a guideline or outline. The danger of an outline is that the strict adherent to it will crush his living characters with it.

AM: Do you believe your book provides justice for the terrorized Sheedy family?

SY: When I began writing, that Quixotic gleam flashed in my eye, and Hettienne Sheehy, my Dulcinea del Toboso, consumed my heart. I saw her at awards banquets, spotted her waiting for school buses in our subdivision, recognized her in the icy superiority of a manager’s face and body language. But, alas! The legend is a giant, a windmill churning to sweep the horseman to his death, or at least to his hilarious shame. Our compulsive desire to believe the outrageous, the preposterous, the sensational, the grotesque, and the depraved is affirmed every day by our credence in fake news.

AM: What do you think the Sheedy’s would think of your book?

SY: They would never read it. Near the end of their lives, the three spinster sisters, last to live and die in that twelve-room mansion, could not even trust workmen to perform routine maintenance, they had lost so much faith in Springfield, in humanity. I have done all I can to give them back a life, love, passion, and dignity by inventing the cartilage, blood, and skin ennobling the bare bones of life events. Yet too much has been trampled, too much burned, too much shattered in ruins. They would think I was just another liar and vandal.

AM: What perspective is your book written from and how did you create this voice?

SY: I knew I had to discover a witness, an heir, the Last Sheehy, a child at the beginning of the novel and a mature woman at its close. Otherwise my choices for protagonists — the spinsters Agnes, Helen, and Margaret — would have me rewriting, “The Jilting of Granny Weatherall.” So with the Sheedy story in my mind, in August of 2013, we were in Oregon with our nieces. The eldest, Lauren Grace, is quite tall, nimble, blonde, humble, and caring, and so lovely, I have witnessed this teenager’s entrance to a restaurant or to a train car silence all conversation. Beauty like an overpowering force field. On the mountain road to Netarts Bay, she took her first meclizine tablet to fight car sickness and rode in the front with me. Along the winding highway, I happened to look over at her — she had fallen so quiet. To my shock, she had been for some time staring intensely at me, quite through me, her face frighteningly blank, mouth gaping. This continued for several intense miles until I whispered her name. With a jolt Lauren Grace returned to us. There was Hettienne, the last Sheehy, who saw the fire, the vandals, and the legend that was looming to curse and consume her family.

AM: What are the differences between a good and bad legend?

SY: If a legend’s tenor and vehicle relies on making a person or a family into a monster, you can almost count on that producing evil, cosmically and practically. And the Albino Farm legend was always so badly told, such nonsense. Yet look what destruction it unleashed! I would rather rewrite “The Fall of the House of Usher,” turn it inside out, illuminate the family story and the love story Edgar Allan Poe missed, transform the affliction of sensitivity into somewhat empowering visions, and place the monstrosity out in the community where horror originates. I didn’t set out to do all that—but that’s how it feels now. There’s no need to rewrite a crazy legend, and you can only rectify some of its impact.

AM: How is The Legend of the Albino Farm similar to your other works? How is this book different?

SY: All that is for readers, if I ever gain any, to determine. I will say this book would not exist without the intervention and shepherding patience of my editor Greg Michalson. I had lived so long in the consciousness that narrated The Teeth of the Souls — a nineteenth– and early twentieth–century novel with bombast and flourish and lush, arcane language — that I almost lost the capacity to write in a contemporary idiom. Greg saved my writing life by never letting up and never letting go.

AM: What’s next for you?

SY: Read, read, read, read. I’m terrified that I almost lost my ability to write in a plain American, Ozark idiom. I’ll be devoting myself to getting this book to every reader it can reach. And then I will be heavily devoted, as I always am, to my work at University Press of Mississippi, where I am associate director / marketing director.

**

Steve Yates is the author of the Knickerbocker Prize-winning Sandy and Wayne: A Novella, the Juniper Prize-winning Some Kinds of Love: Stories, and the novels Morkan’s Quarry and its sequel The Teeth of the Souls. The recipient of three individual artist fellowships from the Mississippi Arts Commission and another from the Arkansas Arts Council, he lives in Flowood, Mississippi, with his wife, Tammy Gebhart Yates. Born and raised in Springfield, Missouri, Yates is the associate director and the marketing director at University Press of Mississippi.

May 2nd, 2017 at 6:23 am

[…] Midwestern Gothic […]