Interview: Gabe Habash

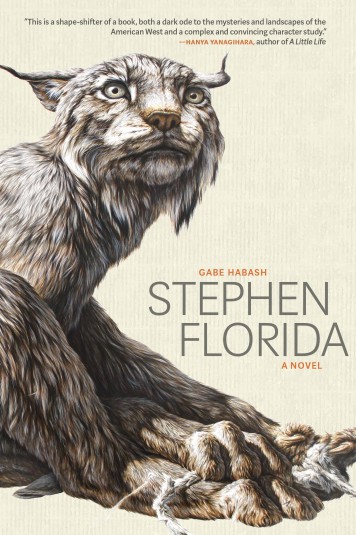

Midwestern Gothic staffer Kathleen Janescheck talked with author Gabe Habash about his novel Stephen Florida, “nowhere space,” being unsettled, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Kathleen Janescheck talked with author Gabe Habash about his novel Stephen Florida, “nowhere space,” being unsettled, and more.

**

Kathleen Janescheck: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Gabe Habash: I was born in Columbus, Ohio, and lived there until going to Florida for college. Most of my family lives in the Midwest, and my wife is from Michigan.

KJ: In your novel, Stephen Florida, your main character is a college wrestler who travels around the Midwest—including North Dakota, Minnesota, Wisconsin, along with other states—as he attends various competitions. Are any of the places he visits of particular significance to you?

GH: I hadn’t actually seen any of the book’s locations in person before writing. I like to have room to make the story. A story can’t be too close to my own experience or I’ll get bored. For instance, I live in New York and so I’d never write anything that takes place in New York. I live here every day, so to remain there when I sit down to write is just kind of claustrophobic and airless to me. So North Dakota and the smallish Midwestern towns that are in the book like Winona, Minn., Kenosha, Wisc., etc., were at the opposite end of the spectrum. The places in the book are significant to me because they had no prior significance; in fiction you have the chance to make them into something significant.

KJ: What made you choose to set your novel in the Midwest, particularly North Dakota?

GH: When I was growing up, we’d drive to the edges of Ohio to visit my grandparents. My mom’s parents lived in Lorain, which is near Cleveland, and my dad’s parents lived in Steubenville, which is right on the state border for both Pennsylvania and West Virginia. Between Columbus, which is in the middle of the state, and Lorain/Steubenville there are these long stretches of farmland and small towns. I always found these nowhere spaces interesting. You can see them in the photographs of Stephen Shore or Ed Ruscha, or even in Edward Hopper’s paintings. When you drive past a big field with a farmhouse plopped in the middle, it naturally makes you wonder because there’s so much to fill in, there’s so much emptiness and room. In my head, North Dakota was the most extreme version of this “nowhere space.” I liked the idea of a character doing something great there, but something only great to him, not because it isn’t impressive but because no one is paying attention. There was so much space to imagine the story.

KJ: Stephen lives and breathes wrestling—he’s more than a little obsessed. When writing about obsession, do you notice any uncomfortable parallels between the story you’re telling and your own experience as a writer?

GH: Yes, my relationship to writing and Stephen’s relationship to wrestling are not dissimilar. I’m not sure how many writers can finish a novel and not be obsessed with it. But the act of writing this book was also cathartic because I had a place to put my frustrations. Writing is usually uncomfortable. Sometimes it’s easy or you can amuse yourself but mostly it’s difficult to articulate the fog in your head, to transfer that onto the page. Then after you finish the first draft, your entire job becomes trying to fix and clean up all the little ways you failed to articulate what you wanted to articulate. When you write a novel, it takes years of your life and occupies so much of your mental space there’s not that much room left over. And the way Stephen handles his wrestling career is similar.

KJ: What about obsession do you think we, as a culture, are attracted to?

GH: I think we like to watch people commit to something, and to grow. Bildungsromans or coming-of-age stories, those imply movement or growth in a character. Obsession is just the extreme version of commitment. So if an obsession story is the most extreme version of a straightforward character arc, the stakes are naturally higher because the character is risking everything, and so will either be massively successful or a catastrophic failure. Then, as a writer, your job becomes making the reader care about the obsession of the character.

KJ: What made you want to write about wrestling? Do you have any personal experience?

GH: I’ve never wrestled, but I was drawn to how intense and unforgiving it is. The brain of a wrestler seemed to me fertile territory for a novel—what kind of person would commit to something so punishing? And the sport itself, with its weight management and fast physicality, was inherently dramatic.

KJ: Much of your novel focuses on the disgusting and the disturbing, and your writing emphasizes these aspects—how do you write about the unsettling?

GH: I like to be surprised both in books I read and in what I’m writing. Being scared or unsettled or disgusted or laughing all come from being surprised. I wrote the first draft of the book in about fifteen months. Because of the relatively quick pace and because I didn’t have all of the blanks filled in for certain scenes, I was able to surprise myself with unsettling or disgusting details.

KJ: How do you write a character with a voice as strong and, presumably, different from your own (such as Stephen’s)?

GH: I’m not sure! I had Stephen’s voice down when I sat down to write the first page, so that made the writing go quickly. I think generally I wanted to keep the voice from being boring and to make it consistently surprising. If I could surprise myself and not be bored, I figured that’d be a good foundation to build on.

KJ: You’ve worked as the Fiction Reviews Editor for Publishers Weekly for a while now. What insights about writing have you gained from that experience?

GH: I’m lucky that my job exposes me to books every day, and forces me to think about them critically as I work through the reviews. The style for our reviews is very short and straightforward—they typically run around 225 words—so editing those reviews every week made editing my book easier and more streamlined because if a sentence wasn’t doing what I wanted it to do, it was easier to think about why it wasn’t succeeding or to be okay with cutting it altogether. Most of the editing process with the book was cutting, and I’m sure it would’ve been a bit more agonizing if I didn’t edit reviews every day for my job.

KJ: Your wife, Julie Buntin, is also a writer—what is it like to have two writers in a household?

GH: We’re both the other’s first reader, and I know I don’t feel good about my writing unless Julie looks at it and gives her approval. When I wrote the first draft, I showed her the first 50 pages and only continued after she approved. Then I didn’t show the book to anyone or talk about it at all until I’d finished the whole draft. Then Julie read it, and after I’d incorporated her edits, only then other people gradually got to read it. The book would certainly be worse if Julie hadn’t helped edit it. And we’ve both largely gone through the first novel process together, so it’s been a lot easier to have someone next to you the whole way.

KJ: What’s next for you?

GH: It’s not real yet so if I articulate it now, then I’m afraid it will disappear and I’ll never get it back.

**

Gabe Habash is the fiction reviews editor for Publishers Weekly. He holds an MFA from New York University and lives in New York.