Interview: Barbara Browning

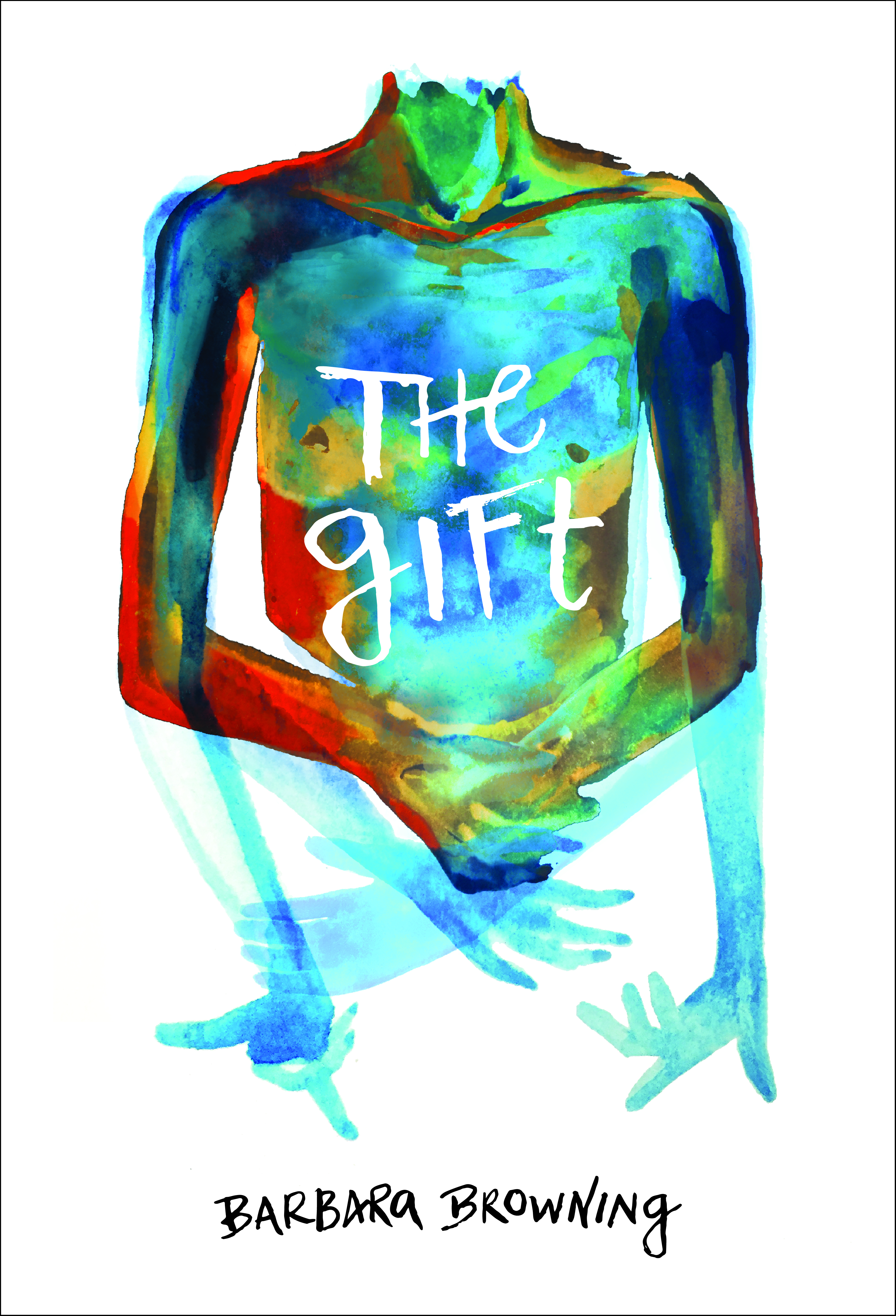

Midwestern Gothic staffer Audrey Meyers talked with author Barbara Browning about her book The Gift, virtual intimacy, collaboration, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Audrey Meyers talked with author Barbara Browning about her book The Gift, virtual intimacy, collaboration, and more.

**

Audrey Meyers: What is your connection to the midwest?

Barbara Browning: I was born in Madison, Wisconsin. My mother was born in Pontiac, Michigan, and my father in Elyria, Ohio. My parents separated when I was six, and when I was twelve my mother, sister and I moved to Northern Virginia, but I think my early years in Wisconsin, as well as my mother’s sensibility, were pretty determinant of something in my voice as a writer.

I’ve made reference to that in each of my novels. In The Correspondence Artist, the narrator says very early on, “my own voice has a certain Midwestern flatness about it. Perhaps you’ve already noticed that.” Actually, she says that on the first page of the book. And indeed, I think by the time they get to that line, readers will already have noticed what I’m talking about. The narrator of my second novel, I’m Trying to Reach You, was different from me in some respects (among them, gender), but we had in common having been raised by a single mom from the Midwest. Barbara Andersen, the narrator of The Gift, also references the Midwest quite a bit. My own mother and sister both ended up returning to Wisconsin, and live there now. Barbara A.’s mother and sister live in Ohio.

AM: How has being a professor at NYU impacted your writing?

BB: I had to introduce myself at an academic talk the other day and I began it by saying “I have the OBSCENE pleasure of teaching in the Department of Performance Studies at NYU.” That’s not actually an exaggeration. I’d been teaching performance theory and research methodologies for some time before I began writing fiction, so unlike a lot of fiction writers, who teach as a way to support their writing practice, which comes first, I began with a desire to teach, and then developed an interest in writing fiction as a way to expand what I was able to do in thinking about the theoretical, aesthetic and political questions in the areas of performance that move me. My students are brilliant, curious, brave, weird, and constantly turning me on to new music, dance and writing. My colleagues are also very precious to me. I end up inspired by them and quite a few have made at least cameo appearances in my writing.

Higher education today is a confusing place to be if you have certain political commitments. That is, it can be a very comfortable sphere, in some ways, if you lean leftward, but in many institutions, including my own, that’s undergirded by the crushing debt incurred by many students. So I think it’s important to keep challenging that, and talking about it, and grappling for ways to address that. It’s a part of the narrative of The Gift.

AM: What inspired you to write The Gift?

BB: In the book, my narrator explains that her readings of theorists of gift economies (Marcel Mauss, Lewis Hyde, David Graeber) in the wake of the Occupy movement inspire her to try an experiment – recording little ukulele cover tunes and spamming people with them in order to possibly stimulate a gift economy of purely sentimental value. I actually did that. And it’s kind of supposed to be funny, but it was also kind of serious. The part about valuing sentimental value over monetary or even aesthetic value was, I suppose, the feminist intervention. My own experiment led to a story very similar to Barbara Andersen’s. It was exhilarating, heartbreaking, scary, and poignant.

AM: What is significant about the virtual world in your book? How do you use it to explore the universal human condition?

BB: In all of my novels, the internet plays a big role – through the email correspondence of my narrator in The Correspondence Artist to the YouTube obsessions of my narrator in I’m Trying to Reach You to the swapping of digital sound and video files between my characters in The Gift. In all three cases, I actually made the digital files (and YouTube pages) that were reference in the texts. I think it’s important to acknowledge that the way we read now has changed. Even when one’s reading novels that don’t reference digital culture, we have a tendency to pause to Google something, and especially when there’s a blurry boundary between “reality” and “fiction” as there is in much of my writing, one has a tendency to want to go down certain rabbit holes. Of course, rabbit holes can be dangerous things. What I always try to encourage my students to do is to toggle between analog and digital. Your question asks about “universality,” and I’m not sure that’s exactly what I’m pointing at, although I also think that questions like the blurry boundary between reality and fiction are hardly new! Cervantes was asking the same kinds of things.

AM: It is thought-provoking that you investigate human interaction by sharing your music to no one in particular through emails. How do you express these connections through words and music rather than other sensory experiences that happen in person?

BB: Ironically, sometimes the voice recorded feels more intimate than the voice in a live conversation, say, in a café. I’m just finishing recording the audio novel version of The Gift, and I’m very self-conscious about my recorded speaking voice. The character Sami in the novel sends the narrator long recorded voice messages. Sometimes those feel even more naked or intimate than a physical encounter might. Sometimes we lose sight (or sense) of that in recorded music, because of the layering of sound or the way production can smooth out the edges – what I describe as the sound of the spit on the lips or the hairs in the nose when you listen to certain recorded voices. I think I say, “It’s almost like somebody’s sticking their tongue in your ear.” I find it interesting to acknowledge how intimate that experience can be.

AM: What did you learn about yourself as a writer when creating The Gift?

BB: Well, I think I knew this already, but this novel was the one in which I really had to confront my sense of obligation to the people in my life who end up incorporated into my fiction. That is, I always ask them to read drafts, and tell me what they’re comfortable or uncomfortable with, even if they’re not recognizable as themselves. I don’t hold that up as an ethical standard for anybody else – in fact, I don’t know of anybody who’s as obsessed with that as I am. For better or worse, it’s a compulsion.

AM: What do you hope people take away from your book?

BB: It’s funny, I had a feeling people would focus on the drama of the relationship with Sami, and the question of whether love at a distance is fulfilling, which isn’t a bad question, but isn’t really the most interesting one to me. I was hoping some of the political questions raised by the book might be of interest – and to my amazement, in fact, early readers seem to be responding to those. That is, I’d like for us, in this moment of great political anxiety and, for many of us, despair, to hold on to some hope, and maybe even utopianism.

AM: Why do you infuse music into your book? In other words, how does music relate to the purpose of your book? And how did this impact your writing style?

BB: Most of the ukulele cover tunes I mention in the narrative are archived on my SoundCloud page (https://soundcloud.com/barbarabrowning). There’s also a Vimeo page (the book has the site and the password in it) where the dance videos are archived. As in all my work, sometimes the music and dance inspires the writing, and sometimes it works in the other direction. Some readers seem to access this work, and others just want to imagine it. That doesn’t really bother me, though I’m always happy if someone told me they took a look or a listen…

AM: After creating The Gift, what does it mean to you to be an artist in the modern world?

BB: Well, I think I always thought something pretty close to Lewis Hyde’s proposition in his book, which is also called The Gift: that loving other people’s art is what makes it possible to make your own, and listening, and reading, and watching are as important and generous acts as making.

AM: To you, how is human interaction a gift?

BB: In the book, the narrator describes her relationship with her son as a “collaboration,” and I think I believe that of all deeply significant relationships – familial, erotic, sentimental. The gift is making something beautiful together, by which I don’t mean a symphony or a skit or a macaroni sculpture, but, say, a comical conversation, or a meal, or a few minutes of silent concentration over a cigarette on the balcony.

AM: What’s next for you?

BB: I have a little book in the 33 1/3 series coming out in September, and in January of 2018, my collaborator Sébastien Régnier and I are publishing a co-authored book, Who the Hell is Imre Lodbrog? We’ve been doing a series of performances about that one – one of the most recent ones is about our trip to Two Rivers, Wisconsin! So, you see, the Midwest keeps coming back…

**

Barbara Browning teaches in the Department of Performance Studies at the Tisch School of the Arts, NYU. She received her PhD in comparative literature from Yale University. She is the author of the novels The Correspondence Artist (winner of a Lambda Literary Award) and I’m Trying to Reach You (short-listed for the Believer Book Award). She also makes dances, poems, and ukulele cover tunes.