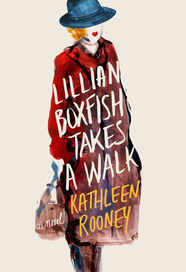

Interview: Kathleen Rooney

Midwestern Gothic staffer Marisa Frey talked with author Kathleen Rooney about her book Lillian Boxfish Takes a Walk, changing the world through writing, balancing fact and fiction, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Marisa Frey talked with author Kathleen Rooney about her book Lillian Boxfish Takes a Walk, changing the world through writing, balancing fact and fiction, and more.

**

Marisa Frey: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Kathleen Rooney: I grew up in the Chicago suburb of Woodridge, Illinois and went to high school at Downers Grove North. As a kid, I couldn’t stand the suburbs (still can’t) and couldn’t wait to move to the actual city someday. Since 2007 (after quite a bit of moving around), I’ve been living the dream. Martin and I have resided in the far north side neighborhood of Edgewater in Chicago for a little over 10 years now, and living in the city itself is every bit as marvelous as my kidself thought it would be.

MF: Lillian Boxfish Takes a Walk takes place in one day—New Year’s Eve of 1984—but is interspersed with scenes from the past. Why did you choose this structure?

KR: Because Lillian is based on Margaret Fishback, the real life highest paid female advertising copywriter in the United States in the 1930s, I needed to find a way to help myself move from the facts of her life and into the realm of fiction. Fishback’s own life and work are fascinating (I wrote an essay about her and helped get some of her light verse on the Poetry Foundation website here, if you’re interested) and I wanted my character of Lillian to be equally so. The key that let me unlock the novel was to give her not just an illustrious past but a really long and incident-filled 10-plus-mile walk across the city she’s known and adored for close to six decades. St Martin’s, my publisher, put the map of her walk on the inside covers, so you could take her walk yourself if you were so inclined.

MF: Lillian Boxfish is loosely based on Margaret Fishback, a poet and the highest-paid female copywriter of the 1930s. How did she come to be the inspiration for the book?

KR: My high school best friend, Angela, was doing an internship at Duke University for her library sciences degree, and she got to help process the Fishback papers when her son donated them to the Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising & Marketing History. Angela is an amazing person and wonderful friend, so she knew that I’d be intrigued by Fishback’s life and work—her proto-feminism, her pursuit of both a career and a family, her serious publication record as a poet, and on and on. Thanks to her, I was able to learn about, apply for, and receive a travel-to-collections grant to be the first non-archivist to work with Fishback’s materials back in 2007. I was immediately smitten with Fishback and knew I wanted to do something with her story, but it took me a while to realize that it would be a novel.

MF: Several of your works—notably Lillian Boxfish and O, Democracy!—are based on real people or events. How do you balance fact and fiction?

KR: Research is inevitably one of my favorite phases of a project because everything at that point is potential energy–you haven’t started really writing yet so you haven’t started making mistakes. For that reason, I could happily dwell in the realm of research indefinitely, but of course that’s no way to get a book written. So when I move from research into writing, I try to be sure that I’ve given myself enough of a plot and enough of a compelling set of characters to sustain the narrative–and hopefully the reader’s interest–beyond the perhaps initially intriguing notion that it’s “based on a true story.” If a novel is too faithfully adherent to the facts of whatever really happened in its real life inspiration, then it probably won’t have the depth of character, the psychological realism, or the plot momentum to keep people reading. You need to give yourself the space to get imaginative and make stuff up, rather than merely novelizing actual events.

MF: What role does this kind of fact-based fiction play in our current cultural environment?

KR: Fiction that’s based on fact ideally calls attention to the fictional aspects of all the things we are encouraged to consider “true.” History, as the cliche goes, is written by the victors, and so good fact-based fiction can offer differing accounts of events that we may think we already know a great deal about. And the fact that fiction has a clear and artificial (albeit hopefully convincing) point of view can in turn emphasize that everything has a point of view–a perspective, an agenda, however you want to put it–and can invite readers to see even real life more complexly.

MF: As a poet, fiction writer, and nonfiction writer, how do you choose what medium to approach a subject with? How do the writing processes differ for you?

KR: Every project needs to find its own best form–you can say things in a poem that you can’t in a novel and vice versa. So I usually know before I even begin writing what genre something is going to be in because form is such a determining factor for content.

And that’s part of why Abby Beckel and I founded Rose Metal Press back in 2006. Our work as editors there has deepened our appreciation of the fact that these genres aren’t really stable and distinct anyway, and that the ones we normally identify are not remotely exhaustive in their description of the forms that creative work can take.

MF: You’re a former U.S. Senate aide—how does having worked in politics shape your approach to writing?

KR: My development as a writer ran in a simultaneous parallel track to my work in Dick Durbin’s office, and I was writing and publishing creatively in the same years as I was working, for instance, as a member of his communications team. (When my memoir Live Nude Girl came out in 2009, they held my job for me while I went on a book tour.) The kind of writing that I was doing in my role as a Senate Aide–speaking as or on behalf of someone else–is vastly different from the creative writing I was doing then and that I do now. Aside from employing basic English language mechanics, the two really did not resemble each other at all.

MF: You’ve said in a previous interview with Chicago Magazine that people can change the world, but not through politics. Do you think people can change the world through writing?

KR: To clarify, I said that people can’t change the world through the politics industry — e.g. working inside a senator or other elected official’s office — because the primary objective in such a situation, especially for a low-level staffer, like I was, is to keep your head down and do what you’re told. Specifically, I said that “Idealists are cannon fodder of the political industry. People most committed to making a positive difference are exploited the most. People who do rise are interested in consolidating their own power.” I think that people can absolutely change the world through politics if by that we mean being politically active–voting, marching, protesting, calling one’s representatives, canvassing and so on and so forth; I believe that being an informed and participatory citizen is part of politics and that you can change the world that way without a doubt.

Writing can change the world, too, yes, for better or for worse. Good writing, hopefully, helps readers develop their sense of empathy for people unlike themselves and for people facing complex moral and ethical situations. But then again, The Art of the Deal came out in 1987 and helped make Trump a household name, and now we’ve got a racist, misogynistic, xenophobic malignant narcissist in the White House and that happened in part because journalist Tony Schwartz helped him write that book.

MF: What’s next for you?

KR: I’m closing in on finishing a World War I novel, which is based on a couple of real-life figures. And I have another novel that’s set in 2016 about a couple of eerie and precocious tween girls in the Quad Cities. Stay tuned.

**

Kathleen Rooney is a founding editor of Rose Metal Press, a publisher of literary work in hybrid genres, and a founding member of Poems While You Wait. Co-editor of The Selected Writings of René Magritte, forthcoming from Alma Books in the UK and University of Minnesota Press in the U.S. next year, she is also the author of eight books of poetry, nonfiction, and fiction, including, most recently, the novels Lillian Boxfish Takes a Walk (St. Martin’s Press, 2017), O, Democracy! (2014) and the novel in poems Robinson Alone (2012). With Elisa Gabbert, she is the author of the poetry collection That Tiny Insane Voluptuousness (Otoliths, 2008) and the chapbook The Kind of Beauty That Has Nowhere to Go (Hyacinth Girl, 2013). Her essays and criticism have appeared or are forthcoming in Allure, The Rumpus, The Chicago Tribune, The New York Times Magazine, Salon, the Poetry Foundation website, and elsewhere. She lives in Chicago with her husband, the writer Martin Seay, and teaches at DePaul University. Follow @KathleenMRooney