Interview: Dan Beachy-Quick

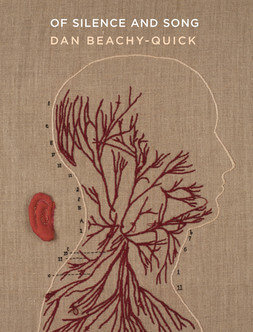

Midwestern Gothic staffer Carrie Dudewicz talked with author Dan Beachy-Quick about his book Of Silence and Song, the formative experience of reading Moby-Dick, writing in the midst of family, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Carrie Dudewicz talked with author Dan Beachy-Quick about his book Of Silence and Song, the formative experience of reading Moby-Dick, writing in the midst of family, and more.

**

Carrie Dudewicz: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Dan Beachy-Quick: It’s two-fold, really. I was born in Chicago, though my parents left when I was just a toddler. I grew up in Colorado, spending summers in upstate New York. But I ended up going to graduate school in Iowa, and then followed my wife back to Chicago, which became for us a true home—a funny thing, as it was my first one. Stranger still, I worked a block away from where my mother worked, lived just a couple of miles from where she did, and had my first child in a hospital down the road from where I was born. Coming back to the Midwest felt as if it drew a kind of circle or cycle complete.

CD: You’ve lived in multiple regions of the U.S.—the Midwest, Colorado, New York, and Iowa, to name a few. How is the Midwest different from the East or West Coast? What aspect of the Midwest is the most impactful to you and your work?

DBQ: The image that most stays with me—one image in many iterations—is the presence of Lake Michigan on the east side of Chicago. I saw it in every season and mood (both its and mine), from a turquoise blue near tropical in its glow, to waves so wild and rough it looked like the North Sea. I suppose I began to fall in that wide expanse of water, so large it had no other side, no horizon of other land, that I began to feel that this inland sea was a symbol somehow of our human condition, that one contains an unimaginable expanse within the borders of one’s own life—heart and mind, memory and thought—and though the outside appearance is one of steady, almost geologic calm, inside the waves crash wild against those very shores. That paradoxical sense—as of a Russian nesting doll, save the one inside is larger than the figure that contained it—is I think the largest creative gift I received from living those years in the Midwest.

CD: You’ve written both essays and poetry about or related to Moby-Dick. Why does this novel influence so much of your work? What inspired you to write at length about Moby-Dick?

DBQ: I graduated a bit early without any planning to do so, and ended up working in a café in Denver, unsupervised for the most part, and in the midst of the shock of no longer being in school, felt very keenly gaps in my education—the most pressing of which, for some reason, was having not read Moby-Dick. So I got it, and read it during my work hours, helped by the endless coffee and almost complete lack of customers. It was the first time I had to do the work of reading all by myself—there was no one to ask questions to, no one to explain. It was, I think, the formative reading experience of my life. I had earnestly been pursing poetry since high school, and somehow I found within Melville’s pages all the questions about the nature of making, of creativity, of word and world, that I didn’t know how to ask myself. It was, and is, my greatest teacher—and most maddening. I came to feel after reading (twice in a row!) that I had some work to do in that book, though I had no idea what that meant or would entail. I felt like I had to investigate, to be responsible to it, to honor it and question it, to enter into it so as to learn to think according to its own inherent laws—and those instincts have come to shape my entire poetic and critical approach. I simply wouldn’t be the writer (or person) I am without it.

CD: Your most recent book, Of Silence and Song, is composed of many different genres—poetry, essays, travel writing, art, and more. Why did you decide to write across genres, rather than just writing a book of poetry or essays? How did the subject of your book inform the form you decided to write it in?

DBQ: I wanted to find a way to work toward other books I love deeply—the quality in them that any page can hold a small wonder that contains a thought or perception or quote or question that livens and almost enchants the page. The preeminent such author for me is Sir Thomas Browne, whose books are learned but never pedantic, personal but never confessional, philosophic but broken apart by wonder, historic but never pedantic. I also wanted a book that broke apart the expectations that one might have in reading it, and doing so, broke apart its expectations of itself. In some sense, the book is trying over and over again to get at the unspeakable thing hiding within words themselves, and to do so, it seemed the book itself knew it needed to work against the ease of its own consistency. I just kind of followed along. I also wanted to write a book that felt truer to our own inner lives, which seems always open to (and broken by) distractions, random tangents, looking up and away from the matter at hand to notice other things, some small and ephemeral, some annoying, some profound but fleeting. I think I’ve long had this sense, almost a kind of desire, to learn to write in such a way that attention became a form of inclusion rather than exclusion. What worried me in this book was the relationship of silence to sound, of oblivion to knowledge, those paradoxes that reveal and conceal at once the ways that what is known and what is unknown are intertwined—and I found myself writing in order to pursue such difficulties, which often meant giving up entirely any notion of easily coherent form.

CD: The description of your newest book says that one of the joys of life you write about is spending time with your daughters. How does your family, and your role as a father, influence your writing? Was there a shift in how you wrote from before you had children to after?

DBQ: As Robert Duncan said of reading William Blake, “it broke the husk of my hubris.” One of the strangest things I’ve found in being a parent is witnessing over the course of many years a person whose life is wholly tuned outward gradually gain this vast inner realm to which I have only the access of what they tell me. It’s both awe-inspiring and frightening, a kind of wonder-terror, a marvel-fear, as the old Greek word deinos implies. I think the most direct influence—and Of Silence and Song is, I hope, a kind of evidence of what I’m saying—is that I wanted to find a way in my writing to reflect the way in which having children wholly alters one’s sense of self and world, and this occurs at levels existential, intellectual, emotional, and putting aside the “high-minded” concepts, also means that while trying to write about the death of John Keats at 5:30 a.m., having woken up early to do so, sometimes you have to listen to Sesame Street while imagining your favorite poet dying in Rome, because the toddler work up, too—and that’s real, that’s necessary, and to deny it is a kind of violence to the rhythm of the daily-familial that I realized I no longer wanted to accept. The holy ground is continual upheaval, not placid hours. That realization, my two daughters, made me a different person, and to write otherwise would be a dishonor to them.

CD: You’re an accomplished writer and you also teach creative writing at Colorado State University. How do these two roles influence each other? What are the most joyful aspects of teaching for you?

DBQ: At times, I must admit, they feel wholly the same. I’ve come to suspect that the classroom-space and the poem-space are eerily similar. At the very least, a good class as I’ve come to consider it invites confusion in, invites in doubt, and in the midst of such complexities, such difficulties, says, “Here is the place of the gathering; here are the grounds of encounter.” That feels to me just what a poem does. Simone Weil writes of the ethical life of an “activity which does not act.” I’ve come to think of poems and classes in just such light: something occurs in each, an activity that doesn’t act, a radical passivity that isn’t indifference but participation at another level—heart, mind, soul. The joys? That indecipherable sense that understanding inches its way toward us because we’ve humbly asked for its approach.

CD: Nature is a theme in your poetry and essays. Do you write outside? Is there a specific place in which you write?

DBQ: In the summer time, and in nice weather in spring and fall, I’ll write in the gazebo in our backyard, dog wandering the lawn sometimes, sometimes asleep art my feet. But also—in the early morning in the living room, and speaking of family and writing, at the kitchen table, with the coffee pot on.

CD: What’s next for you?

DBQ: Oddly, I feel like I’m not the best one to ask. I just wait to see what arrives.

**

Dan Beachy-Quick is a poet and essayist, and author most recently of a collection of essays, fragments, and poems, Of Silence and Song, published by Milkweed Editions in December 2017. He teaches in the MFA Program in Creative Writing at Colorado State University, and his work has been supported by the Lannan and Guggenheim Foundations.