Interview: Matt Young

Photo Credit: Tara Monterosso

Midwestern Gothic staffer Kate Cammell talked with author Matt Young about his book Eat the Apple, the art of passive aggression, the difficulty of writing about memory and oneself, and more.

**

Kate Cammell: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Matt Young: I moved to Fort Wayne, Indiana when I was eight, lived there until I was 18, moved back to attend grad school in Ohio when I was 27, and then I left again. My wife and I go back once or twice a year now to visit family.

KC: Are there any memorable lessons you’ve taken with you from your time spent living in the region?

MY: I learned the art of passive aggression. My family tends to operate on a passive aggressive level anyway, but I think the Midwest amplified it. People are polite (for the most part—there are always exceptions) to a fault. Direct confrontations are rare. They cut you in other ways that are less expected.

On a lighter note, I also learned how to drive in the snow. I live in Western Washington now and have discovered snow horrifies people west of the Cascades—an inch grinds cities to a halt, people abandon their cars on the sides of roads.

KC: Are you conscious of any ways that the Midwest influenced your writing in terms of style or process?

MY: Understanding passive aggression has also helped me harness sarcasm and wit and snappy dialogue. It’s also a good way to build tension and complicated characters. I’m sure the way I think and write and the words I use and the images I focus on are all informed by how and where I grew up in some way as well.

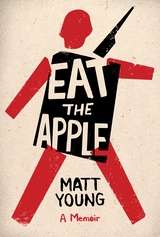

KC: Your first novel, Eat the Apple, a collection of flash nonfiction, was recently released. The stories recount your experience during your three deployments in Iraq. What were the most challenging and exciting parts of addressing your memories from this period?

MY: I didn’t set out to write this book. I initially pushed away from writing about the war and my time in the Marines. I’d tried fictionalizing my experience during my undergrad degree at Oregon State and the stories lacked reflection and nuance, the characters were arrogant and macho and bullshit and I came away from trying to write those stories feeling frustrated and unfulfilled.

When I did eventually write the first few stories for what became the book it was for a grad student reading close to five years after those first attempts at writing. I wanted to read new material and so I turned some bar stories into short nonfiction pieces for the event. The voice that came out was sad, and irreverent and disgusting and it got me hyped. I finished out that first year writing fiction and then that summer I dove into the nonfiction headfirst.

Dredging my past was not enjoyable. Whoever tells you writing is therapy is a cop. That’s utter crap. Writing about memory and yourself is difficult. It takes a lot of reflection and recall. It’s traumatizing to confront a traumatizing past. It was hard to keep that identity at arm’s length. I didn’t always do a good job.

KC: What drew you to the flash form to tell these stories?

MY: I am crap at writing long, for one. But also, I like lyricism and imagery and flash is a great vehicle for those things. Flash nonfiction also mirrors the way memory works—or at least the way my memory works. It’s fragmented and fractured and a lot of the time nonlinear. I do also feel like that form revealed itself; I didn’t go in with that plan. It just kind of happened and I let it happen

KC: Did you work on these stories while you were in Iraq, or did you need to give yourself distance from them and write them after?

MY: Nope. When I was in the Marines there didn’t seem much point in writing. Then, when I left the Marines I wanted to leave it all behind and lose myself in the woods, try and forget it all. I ran away to Oregon for college to be a fisheries and wildlife major. I had this romantic idea of isolation, that I didn’t deserve the comforts of humanity or some such shit. Of course the walking alone in the woods is not what scientists do. It was competitive and fast-paced and the students were very into it. People screeched bird calls in my face. I kind of hated it. Then an English professor suggested that I switch majors to English after I wrote a paper about Stephen Crane’s “The Open Boat.” So I switched, started taking more lit courses and writing courses, discovered there was power in writing, tried my hand at crafting stories about my experience, and hated them, took more writing classes, applied to grad school, wrote stories about the Midwest (a couple of which were published here). Ultimately, I joined the Marines in 2005 and didn’t write a single true word about it until 2014. I needed time.

KC: As a creative writing teacher at Centralia College, you have the opportunity to influence budding authors. Do you have a favorite piece of advice about writing that you share with them?

MY: Mostly, I try to tell them not to be afraid to experiment and to read widely. The intro class I teach covers all four genres. Students tend to be ambivalent about whatever they’re unfamiliar with, but they usually concede that messing around with poetry helps their nonfiction become more imagistic, or memory recall exercises in nonfiction helps with story generation in fiction, or character creation in fiction helps their dialogue in drama.

KC: What’s next for you?

MY: I’m going to try and enjoy the next couple of months and the release of the book as much as I can. My wife’s due with our first kid in a couple weeks. I’ll be traveling and doing events pretty regularly for the next couple months and I’ll be at Miami University in early August to teach a nonfiction workshop and do a reading. Any free time I have will be writing. I’ve got plans but I don’t want to jinx them.

**

Matt Young