Interview: Ruth Joffre

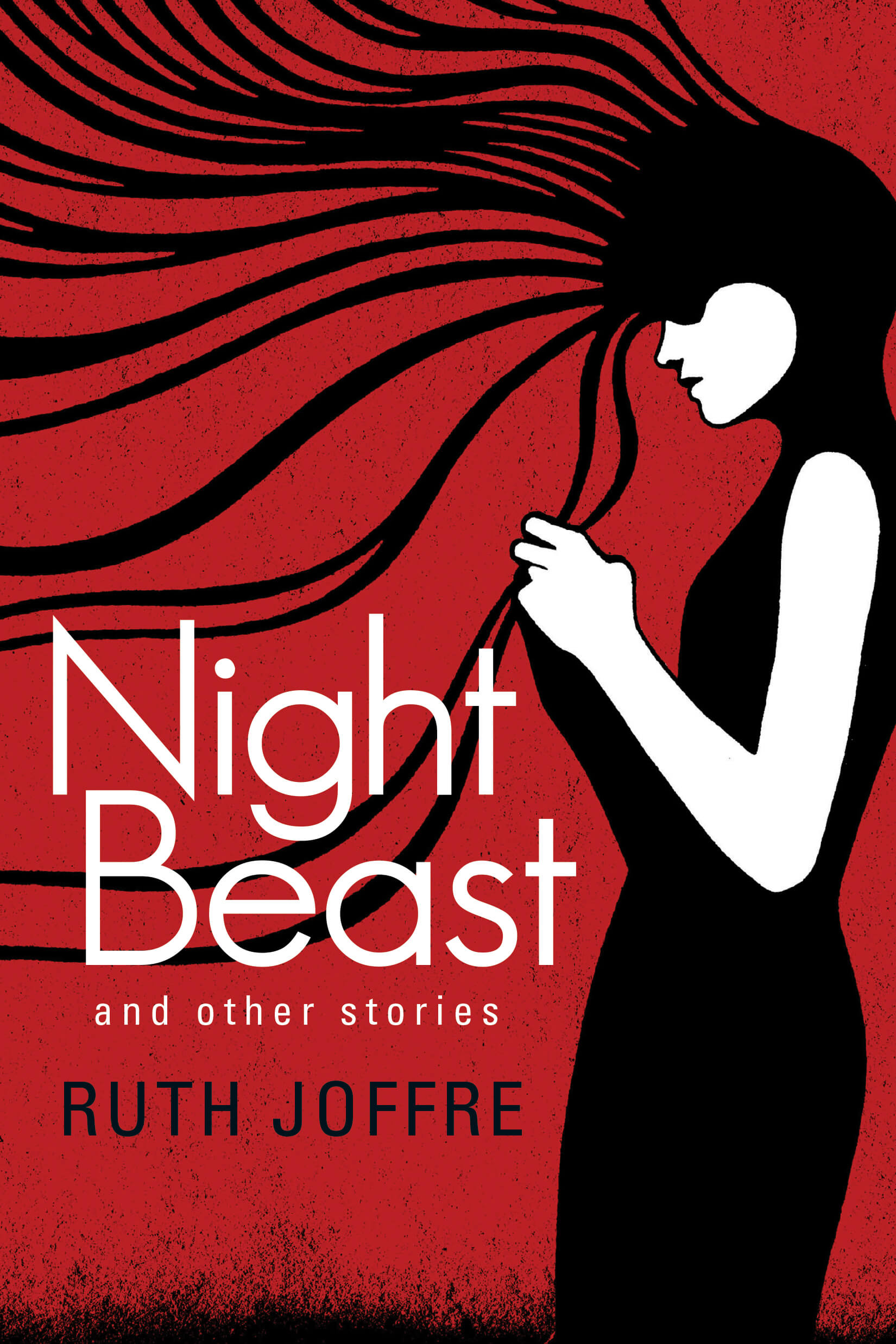

Midwestern Gothic staffer Ariel Everitt talked with author Ruth Joffre about her collection Night Beast, her preference for similes, her ways of finding inspiration, & more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Ariel Everitt talked with author Ruth Joffre about her collection Night Beast, her preference for similes, her ways of finding inspiration, & more.

**

Ariel Everitt: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Ruth Joffre: I lived in Iowa City for three years while earning my MFA at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and working on my short stories. It was the second stop in my slow move westward, which saw me move from Northern Virginia to upstate New York, from upstate New York to Iowa City, then from Iowa City to Seattle. Each move corresponded to a major personal milestone, so for me the Midwest will always be the place where I came into my own as a writer. It was a formative time, and I often think wistfully of the snow and the bitter cold. Seattle’s weather is incredibly mild.

AE: Your new collection Night Beast is full of living, breathing characters whose minds are easy to dip into while reading, but whose true darkness we can only glimpse in their pursuit of human connection. They range from homeless women escaping abuse in the Midwest to college students counting down the seconds until they find love in upstate New York, just as you have lived in both the Midwest and upstate New York. How has your experience in various places across the country influenced your writing?

RJ: More and more, my work is rooted in place. I think moving around as much as I have has shown me how differences in geography and climate can dictate our pleasures, our politics, and our ways of life. For instance, the culture of the Pacific Northwest is so focused on health and fitness, on hiking and fresh fish and trying to ignore the fact that the rest of Washington is a red state, that the people who grew up here think about the world completely differently. Coming from the frozen plains of Iowa, my response to Seattle’s idea of winter was, “You haven’t really suffered.” I associate Seattle so much with white privilege and shocking economic disparity that now whenever I sit down to write I have to consciously push away the safety (however modest) that my life in Seattle has afforded me as a queer writer. Living in so many places has taught me not to write from the emotional, physical, and social spaces I currently inhabit but to instead write from the space that best fits the story.

AE: Is there a significant difference between writing your Midwestern characters and writing your characters from other parts of the country/world?

RJ: Unfortunately, the Midwest was the place where I felt least safe as a queer fat Latina, and even though Iowa City was fairly progressive my time there was marred by the verbal abuse I suffered because of my identity. My Midwestern characters are primarily queer or otherwise marginalized in some way, so that same darkness and lack of safety hangs over them, affecting their ability to connect with others. In “Night Beast,” for instance, the narrator flashes back to a memory of the Iowa cornfields at night and of being advised by her brother to hide her sexuality. This is not to say that my characters that live on the coasts don’t struggle with their sexuality; it’s just that they do so from a place of relative safety (a progressive college campus, for example).

AE: In the story “Go West, and Grow Up,” you write about an unemployed mother and daughter who leave behind an abusive husband/father to live out of their car and struggle to survive this way, kept afloat by hopes of reaching the West. There is working-class literature, which is underexplored itself, but these characters are even a step farther. Was there a personal significance to you, of writing characters in this underexplored socioeconomic class?

RJ: There was a time in my life when I came very close to being homeless, just like these characters. That was in high school. We were moving around a lot, outrunning evictions. My father couldn’t hold down a job, and money was always tight. I escaped very narrowly, but I’ve never forgotten what that was like or where I came from. I think there is very little fiction today that addresses what it’s like to slip through the cracks of society, to move around so much that Social Services can’t find you, and to be abandoned by your government and your country. Increasing economic disparity is only exacerbating the problem, making it even harder for children to escape poverty. Meanwhile, our society’s desire for escapism has made it difficult for stories like these to reach the public.

AE: The tender, tenuous loves your characters forge with one another recreate the complicated feeling of falling in love through language, especially in the stories “Nitrate Nocturnes” and “Night Beast.” Do you employ any particular strategies to help your readers feel all the complexities of what the characters are feeling? And how do you temper the character’s own internal chaos to allow the reader freedom?

RJ: I’m a big fan of simile, more so even than metaphor, and I like creating similes that feel fresh and innovative while also being true to the character’s experience. Many writers use metaphor to make sweeping generalizations (“Love is [x]. Happiness is [y].”), but I like to avoid such direct statements and instead filter them through a character’s point of view. It’s not as tidy, and I’m sure there are some readers who would rather I state things plainly, but that’s not my style.

AE: What’s your personal favorite of the stories in your collection Night Beast, and why? Were there any stories you wanted to include that you didn’t, and, if so, why?

RJ: My personal favorite is probably “Night Beast,” though “Nitrate Nocturnes” and “Weekend” are close. I love “Night Beast” for its exploration of desire and its hostilities. I wanted to include “Some of the Lies I Tell My Children,” which appeared in Nashville Review, but my editor and I ended up choosing the flash pieces that make up “Two Lies,” instead. Those two stories come from a series that explores the same concept in a different style, playing on the idea of fairy tales. Ultimately, the strangeness of the stories seemed to fit better with the other stories in the collection.

AE: How do your stories start (for instance, with an image, a feeling, a line), and at what point do you tend to discover what they’re really “about”?

RJ: Most often, they start with a collection of images (cupcakes at a wedding, the cornfields at night) and expand from there. Rarely do I start with a line. Language comes later, after the images have accrued enough emotional matter to become a story. Most of the time, I know from the start what the story is “about” and where it’s going, but not how to get there. Each line, each paragraph is a surprise that moves me incrementally closer to my destination.

AE: Can you talk a little about how your stories tend to change over the course of revision, and your personal approach to revision?

RJ: I’m a fan of slash-and-burn revision. “Weekend” had a second middle section that I cut entirely. “Night Beast” had a frame story. These pieces are both stronger for their revisions, and it didn’t hurt to make those cuts, though I did resist them for a time. I write so methodically that it can be hard to part with sentences I labored over so long; but it must be done. I come from a workshop background, so when it comes time to revise a story I conduct a lengthy private workshop in my head, interrogating the piece, questioning whether what I wanted to convey is coming across. It sounds crazy, but it works.

AE: Your stories in Night Beast vary greatly in length. For instance, your strange, gorgeous story “Two Lies” is only about four pages long, while “Nitrate Nocturnes” and “Night Beast” are up around thirty. What advice would you give any writer trying to vary the length of their stories? What strategies do you employ in very short stories, and how are they different from those you employ in very long ones?

RJ: When I write long, I usually take every opportunity to expand on the story, to diverge from the primary narrative and delve into a character’s past, but when I write flash fiction I don’t do that. I avoid that detour. I pass that rest stop. With flash fiction, I always keep an eye on my mileage so I can make the trip as beautiful and efficient as possible. So my advice would be to pay attention to your writing habits and identify those places where you would naturally expand on a narrative. Once you’re conscious of that, then you can choose when and where you do it.

AE: What’s next for you?

RJ: Right now, I’m working on a novel called Blood and Sweat. It’s about a drag queen trapped in a massive quarantine in New York City and how he fights back against the oppressive conservative regime. I hope people will have as much fun reading it as I’m having writing it.

**

Ruth Joffre earned her MFA from the Iowa Writers Workshop and is the recipient of the Arthur Lynn Andrews Prize for Fiction and the George Harmon Coxe Award for Creative Writing. Her work has appeared in the Kenyon Review, SmokeLong Quarterly, Prairie Schooner, The Millions, Mid-American Review, The Rumpus, and The Establishment. Ruth currently lives in Seattle, where she teaches writing and literature at the Hugo House.