Interview: Elliot Reed

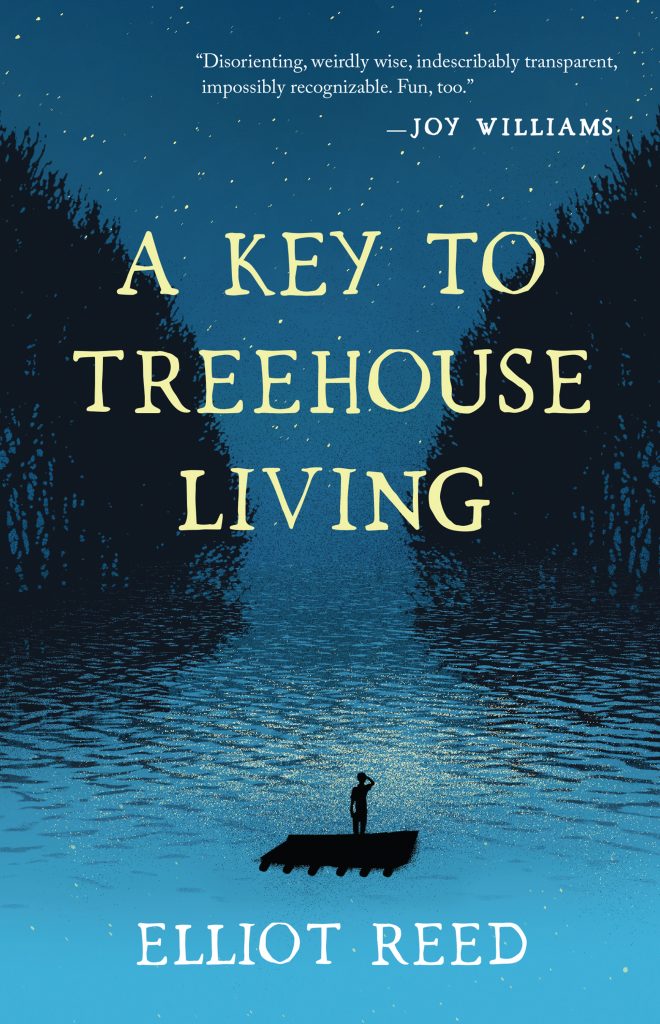

Midwestern Gothic staffer Ariel Everitt talked with author Elliot Reed about his debut novel A Key to Treehouse Living, the importance of creativity to children and adults, and the myths we live by.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Ariel Everitt talked with author Elliot Reed about his debut novel A Key to Treehouse Living, the importance of creativity to children and adults, and the myths we live by.

**

Ariel Everitt: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Elliot Reed: In 2005, my family moved to Columbia, Missouri, so my mother could take a job at the University of Missouri. I entered the eleventh grade there. I stayed through college. I paddled in the Ozarks and fell in love with those streams. I paddled the Buffalo River. After college, I moved out to the country with a friend and we tried to grow vegetables. I lived in a barn. The thunderstorms of the Midwest loved that barn. Then we moved into a double-wide trailer off the two-lane blacktop south of Columbia right before the road descends, becomes gravel, and runs right along the banks of the Missouri. I wrote most of this book in that trailer. I have seen the great clouds of fireflies that frequent the bottoms in summertime.

AE: You grew up in both the American Midwest and the Czech Republic. How have both of these places influenced your writing?

ER: In Prague, where I lived between 2000 and 2005, I experienced a linguistic and cultural alienation that made me want to write. Missouri made me a naturalist. The Midwest is much more beautiful than most people know. I live in Washington State now. I miss being in a sea of foreign language. I recently experienced the linguistic alienation on a beach in Cape Town, where my wife is from, and it was great. There are many languages in Cape Town. I miss living in a place where communication is an adventure.

AE: Your debut novel, A Key to Treehouse Living, takes the unique form of a sort of glossary of the terms, ideals, and myths of an abandoned boy’s life. What strategies did you use to make this experimental form function so beautifully as a narrative?

ER: It was easy and it was not easy to maintain the conceit of this book—that it is an actual utilitarian document, an actual glossary—and this being a novel. I worried about what it was for a while and in retrospect, I’d say that not knowing what it was was a good sign. Donald Barthelme has an essay called “Not-Knowing” that sheds light. Lynda Barry’s What It Is is also good here. I needed to write a story because these places and characters kept coming back. I like writing about things in a glancing way. Each entry bends away from what you could call plot, then bends back in a recursive way. Maybe it’s like a recurve bow. I knew I couldn’t completely digress from a center because I wouldn’t be able to keep writing that way. You have to have a bend, you have to have something made of wood, you have to have the creak of the string tightening, and then, sometimes, you have a release.

AE: Treehouses are, of course, very important to the narrator of A Key to Treehouse Living, young William Tyce. What role did treehouses play in your own childhood, if any?

ER: I fell out of the tree I was climbing just outside a little-league baseball diamond in Roanoke, Virginia, when I was maybe six years old. I had the wind knocked out of me. That was the first moment I understood that one day I was really going to die. When I write well, it’s because I’m writing with an awareness of death. Grace Paley said something like, “Write what you’d die if you did not write,” and this captures what I’m trying to say about mortality and fiction and getting up in trees to find a view.

AE: Did any pieces of fiction or other texts particularly influence your experimental take on the format of this novel?

ER: Padgett Powell’s The Interrogative Mood had a definite impact. I’d also been reading lots of inane internet content like, “THE BEST WAY TO EAT AN APPLE,” or, “FIVE MAJOR SURPRISES ABOUT COOKING BEANS,” and this stuff was really getting me excited. I adopted the imperative mode, at first, with one foot in satire. The first entry was “BUGLING,” and there was William’s voice talking about how one plays the bugle.

AE: Early in A Key to Treehouse Living, some examples of “teaching” the reader how to read the book are clear, such as in the section “ALPHABET,” in which we learn to read this novel as a list in relatively alphabetical order, as well as a sort of progression of development (that a child learns things out of alphabetical order because he is developing). What other methods do you employ early on in your work to “teach” the reader the “rules” of an unconventional piece of fiction?

ER: Hard to say. I knew I had to promise the reader there would be a point, or something like a story, that emerged from these entries. I had to make some connections between entries. Few people would sit down and read through a two-hundred-page, alphabetical glossary of terms relating to a nonexistent source text, but this book might prove that a lot of people would actually come pretty close to doing exactly that. Readers are very surprising. They are deeply suspicious and creative. Give them more leeway and agency than you think they need, but never intentionally obfuscate what you know if you actually know it. Don’t come up with random ways of saying something simple. Write without knowing.

AE: The myths William lives by are incredibly unique, and as a very independent child as well as a sort of orphan, he has had much freedom to decide which cultural beliefs he accepts or even likes. For instance, he dismisses the Christian story of Easter as a boring old myth that has been replaced by that of the more interesting Easter bunny. And certainly, an incredibly fascinating, enriching series of beliefs arises from this child’s freedom to think for himself. How might we hope to give ordinary children and even adults such intellectual freedom, and such space for creativity?

ER: Good question. Give them food to eat and someplace safe to be for a while. Give them free time and give them art. Give them a library card. Make them travel. I could go on and on! I don’t think there is a formula for creativity. Be nice to children and keep them safe, but also let them run around barefoot all the time and live with the wolves. I’ve never had children and I was not the best babysitter but the kids I babysat seemed to like me.

AE: How did you keep such an introspective and instructive narrator from overwhelming the story and weighing it down? Is this perhaps related to how the narrator says it’s hard for him to write about an abstract concept like boredom without “getting distracted by telling something interesting?”

ER: This is a hard question to answer because I find it hard to paraphrase the story of this book—what exactly would he weigh down? There’s a lot of story in this book, and it goes in a few different directions. William can’t really weigh anything down if the book is the testimony he gives in order to stay afloat. I don’t want this answer to sound like a dodge. I don’t mean it to be a dodge. This narrator isn’t going to bore himself when he’s writing. Do you bore yourself when you’re daydreaming? Deborah Stratman, one of my all-time favorite filmmakers, quoted another person, who I don’t know and whose name I can’t remember, who said, “I don’t know what it is to be happy, but I know what it is to be curious.”

AE: A Key to Treehouse Living maintains a gorgeous, dreamy, sweet, and consistent atmosphere, while also hiding and unveiling secrets and evolving as a narrative. Do you have any advice on keeping a consistently wonderful vibe in a story while also surprising the reader?

ER: This book was a gift. William was a wild baby left on my doorstep in the middle of the night. He came with a personality. Still, the book didn’t come out perfectly, and it took a lot of work to keep the thing readable. Tons of people helped me. A fiction workshop at the University of Florida responded very positively when I didn’t know if I had something like a novel. I might not have finished this book had it not gotten a positive response that day. I had more good readers after that, and very good editors. I think I write surprising fiction because otherwise, I’d get bored. It’s also very easy for me to get bored of surprises.

AE: William says it’s important to be able to tell the difference between a good idea and a bad idea. How can you tell if your story ideas are good or bad ones, or is fiction a bit different that way?

ER: I recently heard this one poet say, “When your work has value, you will know it.” You can’t learn how to know the value, thank god. Lifestyle choices can affect your taste, moment to moment. Certain moods or states of mind could improve or degrade your ability to pass judgment on your own work. I write sober.

AE: William says he once knew a kid who “called grass ‘skin’ and rotting wood ‘slug’ and I don’t remember much else but it was a really good language and I sometimes wonder if his language is still alive somewhere, but I don’t hold out much hope.” What do you do to keep your own language alive and uniquely your own? What value do you find in technically incorrect or bizarre usages of language?

ER: Deliberate misuse of language in the service of flair is usually bad writing. I say usually but I can’t really think of an exception. I’m sure there is one. Maybe Gertrude Stein? Even she is not misusing language or using it technically incorrectly—she’s using it perhaps in a bizarre way. Consciousness is paper-thin. Language is that plant-based fiber from which self-consciousness is woven. According to Strunk and White, every word should tell. I don’t know if I possess my language, but I can add to a collective language when I communicate.

AE: How did you approach the order in which events of William’s life come out in this not-quite linear narrative? How did you integrate these events into entries so smoothly, without making it feel forced?

ER: When I knew what was happening to William—rather than what he was trying to define at that moment—I let him describe what had happened. Sometimes he describes it in a glancing way, or as a side note in whatever it was he was interested in thinking about or explaining at that time. This changes about halfway through the book.

AE: In A Key to Treehouse Living, William draws inspiration from many books, including the glossary of one called FLYNN’S GUIDE TO WOODY TREES AND SHRUBS, EIGHTH EDITION. WITH ADDITIONAL FLOWCHARTS AND EXPANDED GLOSSARY. What are a few of the terms might you include if you wrote a guide to writing in such a glossary format—a REED’S GUIDE TO WRITING FICTION—and what lessons might you impart?

ER:

WILD-DOG ATTACK: A lie you once told to a friend, about a friend you had in common being attacked by wild dogs on his way home from a party. He was never actually attacked. Fiction is not supposed to be lies. Fiction is not supposed to hurt anybody, but it’s supposed to hurt.

EDITOR: A person who seems to understand what you’re trying to do 85% of the time. You only understand what you’re trying to do 10% of the time. Nobody understands what you are trying to do 100% of the time. Nobody should ever understand.

THE HOLY GHOST: A celestial entity made from a black hole and some puppies that got dumped off in the woods by a family who didn’t want them. This celestial entity understands that you do not understand, and can never understand, the extent to which your editor or readers understand your work: the chasm is impossible to bridge. Only the Holy Ghost can cross it.

READER, GOOD: A person who understands what you’re trying to do some of the time, but by no means all, and who will tell you something helpful some of the time. Mostly, this reader will not tell you things that are unhelpful.

MOUNTAIN CARIBOU: There are very few of these majestic animals remaining in the inland rainforests of the Pacific Northwest. Scientists describe these caribou as “wilderness dependent.” Find them and observe them from a distance. They do surprising things like migrate to higher elevations when winter comes on. Find your mountain caribou and observe it from a distance. It is on the verge of extinction. Do something to save it, and have fun while you’re at work.

COLE-SLAW STORY: Narrative that has the look and texture of cole-slaw. Sometimes it is too sweet. This story can be the perfect kind of salad.

**

Elliot Reed received his MFA from the University of Florida in Gainesville and is currently living in Spokane, Washington.