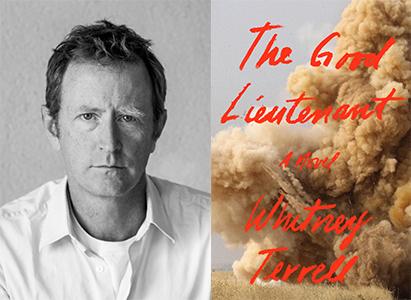

Midwestern Gothic staffer Lauren Stachew talked with author Whitney Terrell about his novel The Good Lieutenant, re-structuring his novel into reverse chronological order, writing from a military-woman’s perspective, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Lauren Stachew talked with author Whitney Terrell about his novel The Good Lieutenant, re-structuring his novel into reverse chronological order, writing from a military-woman’s perspective, and more.

**

Lauren Stachew: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Whitney Terrell: I was born and raised in Kansas City. My family has been living here since the 1890s, on my mom’s side. And that side of the family moved here from Nebraska so . . . I think it’s safe to say that we are not a coastal family. On my dad’s side, his father grew up in Holton, Kansas, fought in WWI, went to law school at Kansas University and then moved to KC.

LS: Apart from living in the East Coast while attending Princeton University, you grew up and have lived most of your life in Kansas City. How did briefly living in a different region of the U.S. affect your conception of the Midwest?

WT: Like many young writers, I had an excessively romantic view of the East Coast, and New York City in particular. I thought of the Midwest as a place I needed to escape. Going to Princeton as an undergraduate did nothing to dispel this. What did change my conception of the Midwest was moving to New York after graduate school in 1996. I was pretty broke. I had a small shotgun apartment on E. 13th Street—an area that wasn’t yet as gentrified as it is today. I was fact-checking for The New York Observer. I liked living in the city. Loved it, really. I could feel myself being absorbed into its routines.

At the same time, in the mornings before I went to work, I began writing for the first time in my life about Kansas City. These were the opening pages of The Huntsman. On 13th Street, the world I’d left sounded exotic. Nobody there knew what it was like to build a raft and float down the Missouri River, as I’d done when I was sixteen. Nobody there had smelled the inside of a gas-lit hunt club. After fact-checking other people’s writing during the day, I began to look forward to imagining Kansas City in my own words. The feelings, smells, faces, voices, accents, streets, trees, and people of that city—and my awareness of the city over time—that was my material. That was what made me unique. I didn’t realize this until I lived on lucky 13th Street.

LS: Both of your previous novels, The Huntsman and The King of Kings County, address issues of race: the former centers on a young African American who finds his way into Kansas City’s white, upper-class society while searching for answers about his family’s past, and the latter focuses on the relationship between real estate and race in Kansas City. What made you interested in exploring this topic in your novels?

WT: The person I have to thank for that is James Alan McPherson. He was one of my professors at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and he was an incredibly powerful influence, a deeply caring, thoughtful, and generous mentor—at a time when I really needed a mentor like that. At Iowa, I was writing about Alaska, where I’d spend summers working on seine boats, fishing for salmon. McPherson was encouraging about that book. But in the end, his seminars and his lectures were more important. He was intensely interested in race. We read and discussed all the greats: Ralph Ellison—particularly the essays—Richard Wright, Toni Morrison, Dubois, Walker, Hughes and many, many more. (I’d include McPherson’s own work on this list, though he never did.)

McPherson also insisted that white writers had a responsibility to engage with the subject of race in their own work. He called it the “great American subject.” I can remember a terrific lecture he gave on Melville’s “Benito Cereno,” for example. This had a profound influence on me. Also, his way of talking about race was helpful. He was funny. He teased. He questioned. He was an iconoclast. He led his classes through a never-ending seminar on America’s historical and ongoing attempt to grapple with race and diversity. I took to heart his assertion that, as a white writer, these issues were part of my heritage too. Something I had a responsibility to engage with. Kansas City only became an interesting place for me to write about when I began to view it through this lens. In the 1990s and early 2000s, as I was writing The Huntsman and The King of Kings County, Kansas City and other northern and Midwestern cities like it were basically operating like apartheid states, long after the civil rights era had passed. People in the African-American communities of those cities were well aware of this. So were other writers. But it wasn’t part of our national conversation. It was a buried story—one of many.

For instance, The King of Kings County focuses on how real estate companies used racial covenants to segregate Kansas City. I discovered as I did my research that many people knew about this, but it had been kept out of the official histories of the companies involved—and omitted from the city’s history generally. I wanted to force this history into view, make it visible in narratives that people couldn’t ignore. For a long time, I felt like I’d failed. The books were well reviewed, but outside of Kansas City, maybe, I didn’t feel like they had much effect. Now, after Ferguson, and Baltimore, and Chicago—the painfully long list of cities where we’ve seen protests—these kinds of stories are in focus. People are paying attention. Excellent new books are being published. My students talk about these issues. It’s insane that it has required more than two years of protests, in cities across the country, and the deaths of numerous unarmed black citizens at the hands of the police to get mainstream America, and especially white America, to make this a part of our national conversation. But I’m not surprised. Resistance movements like Black Lives Matter are responding to a deeply seated structural racism that the residents of all these cities had known about for decades. I knew about it. Thanks to McPherson, I was able to write about it in those early novels. The subject has only become more and more urgent. I hope people will revisit those books now.

[Note: James Alan McPherson died this past summer, after this interview was completed. A number of his former students wrote about their memories of him on literary sites and on social media. I wrote my own piece for Literary Hub, which you can find here: http://lithub.com/obama-america-and-the-legacy-of-james-alan-mcpherson/]

LS: Your most recent novel, The Good Lieutenant, opens with a failed Army operation in Iraq led by the main character, Lt. Emma Fowler, and from this point the narrative moves in reverse chronological order. How did you arrive at this structure? Did you always intend for the novel to operate this way?

WT: I wrote the novel in chronological order originally. Never considered going backward. My current editor, Sean McDonald, read the book in that original form. He told me, “Look, the last hundred or hundred and fifty pages of this are good. You just need to get to them more quickly.” The book was over three hundred pages long at the time. Even so, I was fine with his suggestion. I was just glad that an editor thought that there was some part of the book that was worthwhile because by then, I’d been working on it for about six years and still wasn’t happy with it.

So I cut the beginning. I tried to write something new that could be grafted on to those 150 good pages. But it seemed like no matter what I tried, I couldn’t gain any momentum. These scenes were boring, slow, and clunky. I worked at this for six or eight months until finally I realized I just couldn’t do it. Here was this terrific editor—I’d known about Sean for years and really respected the writers he published—who was interested in this book, and had given me this completely reasonable suggestion to fix it, and I was still going to fail. I was sitting right here at my desk on the day that I gave up. It was a beautiful spring day. I was miserable. I had selected the last forty pages of the novel and was trying to imagine how I might be able to turn them into a short story, so I could at least get something out of this project. But no luck. Even in that shortened form, I realized that the ending of the novel was too narrow, too deterministic, too negative. The message was, in essence, “Hey, look, the war turned this woman’s life into a mess.” Not a very original idea. The various chapters of the book were spread around me in a mess. I kept paging through that last scene, hoping to find a way to save it. Somehow, a scene from earlier in the book got mixed in underneath those final pages. When I arrived at it, I actually had an idea. A very rare moment of inspiration. I realized that if I told the story in reverse, the ending wouldn’t be so narrow. Instead, the characters would grow and complicate themselves as they moved away from combat. The novel would have that crucial feeling of expanding outward—without giving up my belief that war is not, in fact, an avenue for character growth.

LS: In 2006 and 2010, you embedded with the U.S. Army in Iraq and covered the war for The Washington Post Magazine, Slate, and NPR. How much of this experience inspired or informed the story and characters in The Good Lieutenant?

WT: Those experiences were crucial. Especially the embed in 2006. In my mind, that’s roughly when the book takes place—though I don’t specify a year in the text. I’ve always been a really place-oriented writer. So just on a basic level, it was extremely important for me to be present in that physical space. Sensory inputs are irreplaceable. What does an Iraqi shopping center look like? What do the road signs say? What’s on TV? I remember attending this one, extremely long meeting at a schoolhouse out in the countryside, outside the wire. The lieutenant colonel from the battalion I’d embedded with wanted to meet with a group of local sheikhs to try to convince them to stop letting insurgents travel through their neighborhood. The text of the conversation is one thing—I have that in my notes. It tells you that neither the sheikhs nor the colonel were fully in control of their territory. They needed each other’s help but didn’t trust each other. They were still trying to figure out what was causing the uptick in violence they were seeing in that area. (The answer was that we were witnessing the beginning of a civil war between the Sh’ia and the Sunnis in that area. But this was only clear in retrospect.)

So that would be the “story” in a journalistic sense. But as a novelist, there are so many other things to see. How the sheikhs dress, the kinds of cigarettes they smoke, the soda they drink, the cell phones they use. There’s a donkey tied up in back of the schoolhouse, braying the whole time. There’s the colonel’s interpreter, wearing an Iraqi Army flag on his shoulder, looking smug and disdainful as he translates what he believes to be yet another digression from one of these sheikhs. Or giving one word translations when the guy has just shouted for several paragraphs. There are the empty cubbies used by the children who have class in that school room. Chalk boards. Kids’ drawings on the walls. A map of the world with the Middle East in the center of the page, just as our world maps at home put America in the center. A bunch of open paint tins stashed in the corner, with the brushes still stuck inside them, as if somebody had just painted the walls of the school room in preparation for the U.S. colonel’s visit. Or maybe they had painted over something they didn’t want the colonel to see.

So yes. It was important.

LS: Was it a conscious choice to have a female frontline officer in this novel? Writing from a male perspective, did you receive any criticism for this decision?

WT: Emma Fowler was the protagonist of this novel from the beginning—even before I ever went to Iraq. I never once imagined the novel as being about anybody else. I knew only a few basic things about her. I knew that she’d been in ROTC and that her mother had left the family when Emma was a young girl, and that Emma had grown up having to care for her brother as a kind of replacement mother. I knew that, as an officer, at least in the beginning of her career, she was a very rule-oriented person. Very much about toeing the line, following procedure, and that she took comfort in that—and that this specific aspect of her character would be challenged as her time in the Army and her time in Iraq progressed. That was it, in terms of facts. I did, however, have this internal, instinctive feeling about what kind of person Emma was. For a long time, this was just a feeling. I could say to myself, “Well, she would react this way in this kind of situation.” Or, “That doesn’t sound like something she’d say.”

The long process of writing the book was in part a process of developing a fully coherent, explicit understanding of this instinctive feeling. Why did Emma care so much about following procedure? How did her past inform her present? What was her ethic?

As for why I chose a female character, it’s honestly difficult to remember with any clarity. It feels like I wanted to write about Emma Fowler specifically. Not just a generic “female officer.” The best I can say is that I knew women were serving in Iraq and Afghanistan in unprecedented numbers. This seemed interesting on its face. And I think it’s always useful, when you are writing about an institution like, say, the Army, to have a character who is part of that institution but at the same time separated from it. And outsider. Draftees played this role in a lot of previous war novels—but of course there were no draftees in Iraq.

So those considerations may have played a role. What I can say, with absolute certainty, is that once I started interviewing and meeting with female soldiers, in Iraq and in the States, I became immediately aware that their stories were fascinating. Their stories were also different than any war story I’d ever read or seen. And beyond that, they felt that their stories weren’t being told. Fortunately, that is changing. Authors like Helen Thorpe, Kristen Holmstedt, Helen Benedict, Kayla Williams, Odie Lindsay, and Cara Hoffman have also published books that address the experiences of female soldiers. I know several female veterans like Teresa Fazio and my former student, Anne Kniggendorf, who are working on books about their military experience. They should be published too. If I can, I hope to help with that. As for the last part of the question, the most gratifying part of this process has been showing the novel to the women who consulted with me on it. Asking them to read it. Talking to them about it afterward. Having them say, “Yes, the book gets this right.”

To me, The Good Lieutenant is a collaborative work, more than anything I’ve ever written. I couldn’t have done it on my own. Women like Major Stacy Moore, former Sergeant Angela Fitle, and Lieutenant Colonel Jen McDonough, all of whom consulted on the book, are its authors too. So are the male soldiers I embedded with like former Captain Nate Rawlings, and Sergeant Travis Parker. I’ve been lucky enough to do events with them on tour, let them talk about their own experiences in person. You can find recordings of these events and interviews on the FSG blog Work in Progress, at New Letters on the Air, and at the Politics & Prose website.

LS: You’ve taught at the University of Missouri-Kansas City since 2004. Is there a piece of advice you always give your students?

WT: Write every day, if possible. Repetitive effort is the best way to solve problems. Try to keep your schedule as clear as possible. Okay, you’ve got to teach, or do whatever’s necessary to pay the rent. Do that. But otherwise, keep your overhead low. Don’t sign up for extra classes in an effort to hurry up and get your degree. Try not to fill your schedule with extracurricular activities. Leave your days open. Dealing with the pressure that open, unscheduled writing time presents is crucial to becoming a writer. An MFA program should be a protected place that is designed to provide you with that kind of time. You should think of this unscheduled time as the most important class you’ll take. You, alone in a room, with nothing to do but write. It takes a long time to get used to living that way. School is where that process begins.

LS: What does a typical day of writing look like for you? Do you have a certain routine or schedule that you stick with?

WT: I drive one of my sons to school and am back at my desk by 8:30. I generally work until 3:00 or 4:00. I go for a run. I eat dinner with my family. I grade papers at night. Rinse, repeat.

LS: What’s next for you?

WT: I’m on a flight to Pittsburg, where I’m excited to do an event with an Iraqi poet, Sabreen Kadhim, at City of Asylum. More generally, another Kansas City novel will be next. I’ve started on it.

**

Whitney Terrell is the author of The Huntsman, a New York Times notable book, and The King of Kings County. He is the recipient of a James A. Michener-Copernicus Society Award and a Hodder Fellowship from Princeton University’s Lewis Center for the Arts. He was an embedded reporter in Iraq during 2006 and 2010 and covered the war for the Washington Post Magazine, Slate, and NPR. His nonfiction has additionally appeared in The New York Times, Harper’s, The New York Observer, The Kansas City Star, and other publications. He teaches creative writing at the University of Missouri-Kansas City and lives nearby with his family.

October 20th, 2016 |

Midwestern Gothic staffer Sydney Cohen talked with author Sarah Bruni about her debut novel The Night Gwen Stacy Died, mixing comic books and novels, living inside a borrowed story, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Sydney Cohen talked with author Sarah Bruni about her debut novel The Night Gwen Stacy Died, mixing comic books and novels, living inside a borrowed story, and more.

**

Sydney Cohen: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Sarah Bruni: It’s where I grew up and where most of my family still lives, in and around Chicago. I also spent four years in Iowa City during college, and three in St. Louis during and after an MFA program, so although I haven’t lived in the Midwest for nearly a decade, it’s the part of the country where I started reading and writing, where I’ll always have deep personal roots.

SC: Your novel, The Night Gwen Stacy Died, heavily incorporates aspects of the classic Spider-Man comic books through the characters’ names as well as their adventurous spirits. Spider-Man lore is an interesting component of pop culture to incorporate in a novel. What inspired you to weave comic book fiction with your own narrative? What were the challenges of this process?

SB: A character appeared in a short story I was working on and surprised me by introducing himself as Peter Parker. At the time I knew virtually nothing about Spider-Man; I was never a comic book reader. But I was curious about the kind of life history and reading habits that would lead to that particular kind of delusion. When I realized that Peter would become a central character in a larger project, I read a decade or so of Spider-Man comic books, which allowed me access to the fictional world inside of which my character had grown up.

The challenging, and compelling, part of working with the narrative spaces of comic books was navigating how the borrowed parts of that fictional world would be grafted onto the working lives of my characters, and how different the result would look through the eyes of Peter and those of my female protagonist, Sheila, as they each interpret and borrow from the parts of the comic books narratives that suit their own needs.

SC: The Night Gwen Stacy Died further plays with and intertwines the genres of fantasy, thriller, and coming of age through character Sheila Gower’s somewhat surreal and mischievous relationship with Peter Parker. What draws you to these genres, and how did you navigate between them to create a cohesive novel?

SB: I can’t say that I was consciously aware of moving between these genres while writing. I think that often as writers we construct the narrative blind, as dictated by the necessity of characters’ motivations, and only later we learn how the work might be classified. In my case, it was news to me that my novel negotiated the borders between thriller, fantasy, and coming of age fiction. I like this intersection, but I can’t say it was ever a clear ambition of mine.

SC: The novel takes place in a journey across the Midwest, from small town Iowa to Chicago. How does the geographic setting of the Midwest influence other aspects of the novel? Besides geography, what elements of the Midwest play a role in the characters’ motivations, personalities, or otherwise?

SB: I feel that in some way each of the protagonists suffers from a kind of Midwestern variety of loneliness in which nothing is necessarily or clearly wrong, or if it is, problems are not discussed. Mostly, I was interested in the tension that existed between a mundane Midwestern working world and a hyperbolic imagined one. After Peter and Sheila flee Iowa for Chicago, not much about their actual day-to-day lives change: they quickly begin working regular hours at mimimim wage jobs similar to those they left behind. There’s a stubborn practicality inherent even in their sense of adventure and change, which strikes me as particularly Midwestern.

SC: Your novel deals largely with the influences that stories have on one’s identity creation, specifically dealing with Peter Parker’s assumption of the classic comic book hero’s name. What interests you about the dynamic of identity and literature? How has your own identity been influenced by the stories you’ve read?

SB: Like a lot of writers, I probably spent too much time reading and observing as a kid, which I’m sure had a direct effect on my gravitation toward writing. I have always been fascinated by the way that literature provides access to other worlds that we can imagine existing inside of and how they influence who we become and the choices we understand as available to us.

In this novel, I wanted to experiment with making literal the idea of living inside a borrowed story, to the extent that the characters’ identities become confused by their relationship to it. I wondered what might happen if a character truly occupied his version of such a story, how the relationship between a personal history and an appropriated one might generate discord as versions of self complement and contradict one another.

SC: The Night Gwen Stacy Died is your debut novel. What surprised or challenged you about your writing process? If you could start over from the beginning, would you do anything differently?

SB: I drafted so many different versions of this book over the course of years. It grew out of a short story collection in which only one story featured the protagonists of the novel. So it surprised me that it grew into a novel at all. Early on, I resisted allowing the book to change significantly throughout those drafts, which made the process toward publication quite a long one. As a writer it can be difficult to learn how to relinquish control of the project and let it grow into something else other than the thing originally envisioned. As much as I might wish to have been more efficient in embracing the project’s shifts, I also understand that my process tends to be very slow and deliberate.

SC: What is your ideal writing environment – the sights, scents, and sounds?

SB: I prefer to write at home in the early morning hours. I have a difficult time working in public places because I’m very easily distracted by any kind of conversation or external stimuli that can drag me pretty quickly away from writing. The most ideal conditions: on a porch or near an open window, with fresh air, endless coffee, and complete silence. I tend to move around a lot and share a variety of living spaces, so I can’t say that those conditions are always, or even often, met.

SC: What’s next for you?

SB: I’m finishing up an MA in Latin American studies and literature at Tulane in New Orleans this fall. The chance to spend a few years studying literature in a tradition outside of the one I grew up with has influenced the way I’m thinking about narrative lately. I’ve been writing a piece that might be growing into a new novel manuscript. That’s my hope for it anyway.

**

Sarah Bruni is a graduate of the University of Iowa and the MFA program at Washington University. She has roots in Chicago, taught creative writing in St. Louis and New York, and volunteered as a writer-in-schools in San Francisco and Montevideo, Uruguay. The Night Gwen Stacy Died is her first novel. She currently lives in New Orleans, where she is pursuing an MA in Latin American studies and literature at Tulane.

October 13th, 2016 |

Midwestern Gothic staffer Sydney Cohen talked with author Margot Livesey about her novel Mercury, different concepts of sight, a different type of infidelity, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Sydney Cohen talked with author Margot Livesey about her novel Mercury, different concepts of sight, a different type of infidelity, and more.

**

Sydney Cohen: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Margot Livesey: The first summer I visited the States I took a greyhound bus from New York to Chicago and immediately liked the city and the people I met there. All these friends of friends were immediately so kind and welcoming. Many years later I returned to teach at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. On my first morning in Iowa City, I think this was 1991, I stopped to buy petrol. Only after I had filled my car did I discover that I had no money. I offered to leave my watch and the petrol attendant said no, just come back when you can. That readiness to believe the best of people exemplified my first visit to Iowa City, and those that have happily followed in 2005 and now when I have a permanent position.

SC: Your new novel, Mercury, deals heavily with the thematic concept of sight, both with literal eyesight and figurative blindness. What interests you about the dynamics of sight, and how does sight work to enable or hinder the characters in the novel?

ML: I’ve long been interested in vision, both in a physiological and a metaphorical sense. We call eyes the windows of the soul and we attribute great significance to them. My interest initially stemmed from my many visits to optometrists as I struggled with contact lenses. Better or worse, the optometrists kept asking. Often I couldn’t say. I have also had the good fortune to know several very competent blind people; watching them navigate the world has been a privilege. When I had the idea for Mercury, it occurred to me almost at once that making my protagonist, Donald, an optometrist would give me a wonderful opportunity to explore how there’s more to seeing than seeing. No one’s vision is 20:20.

SC: As a native of Scotland who has lived, worked and taught around Europe and the United States, how did your geographic and personal background play a role in the inspiration for Mercury? How has the Midwest influenced your writing?

ML: It’s no accident that Donald, like me, grew up partly in Scotland and longs to spend more time there even while he appreciates many aspects of his American life. Meanwhile Viv, his wife, a wonderful equestrian, grew up in Ann Arbor, works in mutual funds in first New York and then Boston and now runs a stables outside Boston. Even Mercury, the horse that changes everything when he arrives at the stables, has also had a peripatetic life.

I find the land around Iowa City, with its gentle hills and small towns, particularly appealing but I would have to say that the Midwest has influenced me more through its people than its landscapes, but then the people are shaped by the landscape. I do think that a MFA program, like the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, could only exist in the Midwest. In the heart of the heart of the country we are all somewhat protected from the forces of commerce. I like both the ease and the complications of living in a small town where writing is cherished. My association with the program has enabled me to grow as a writer, and to be both stubborn and patient.

SC: What were your inspirations for the dynamic and complex characters of Donald and Viv in Mercury – characters who operate through grief and ambition? Why did you make the characterization decisions you did when portraying the tumultuous intricacies of marriage?

ML: A great deal has been written about sexual infidelity in marriage but I am interested in another kind of infidelity: namely what happens in a long relationship when one partner changes and the other doesn’t. When they meet, Donald and Viv share certain beliefs and values. After Mercury arrives, Viv gradually abandons several of these beliefs in a way that is deeply complicated for Donald. They both find themselves in a situation for which life has in no way prepared them.

SC: You published your first book in 1986 and have written extensively since then. In what ways has your writing evolved since the publication of your first book to your newest? Have these changes largely been in one area, such as writing process or style, or a combination of many aspects?

ML: I have the good fortune to teach wonderful graduate students so I spend a lot of time thinking and talking about their fiction, trying to figure out what makes a story or a novel work. In my own work I keep trying new things in terms of plot, character, structure and language. As Virginia Woolf remarks, the world keeps changing and it’s the job of the novelist to reflect these changes. Mercury is my first novel set entirely in the States and that enabled me to explore themes that I couldn’t in a British setting. And of course I got to write American sentences.

SC: Mercury, as a novel that explores the selfish and corruptive aspects of marriage and human nature, can be described as dark, thrilling, and terrifying – much like gothic literature. What draws you to the genre of gothic fiction?

ML: I don’t think of myself as writing gothic fiction but I am interested in dark coincidences and characters who are just a little larger than life. I love, for instance, Daphne Du Maurier’s Rebecca and Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre, novels in which the heroine finds herself completely misunderstanding a person, or a situation. And I do love a good story. The best gothic novels are like well made machines, everything working together to bring about the moment of revelation.

SC: Of the many books in your repertoire, which was your favorite to write, and for what reason?

ML: Eva Moves The Furniture. The novel is very loosely based on my mother’s life and was written with many false turns and much despair over twelve years. I lost my mother when I was very young and for a long time it seemed that the book I was trying to write about her was also lost. But when I finally wrote the ending, I knew I had reached the place I’d been trying to get to all along. I wrote the last chapter in a single sitting, blinking back tears.

SC: What’s next for you?

ML: I am working on a book of essays about the craft of fiction. It’s called The Hidden Machinery and will come out next summer from Tin House. And, of course, I’m trying to start another novel.

**

Margot Livesey was born and grew up on the edge of the Scottish Highlands. She has taught in numerous writing programs including Emerson College, Boston University, Bowdoin College and the Warren Wilson MFA program, and is the author of a collection of stories and seven novels, including Eva Moves the Furniture and The Flight Of Gemma Hardy. She lives in Cambridge, MA and is on the faculty of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Her eighth novel, Mercury, will be published in September, 2016. In July, 2017, Tin House will publish her book about the craft of fiction: The Hidden Machinery.

October 6th, 2016 |

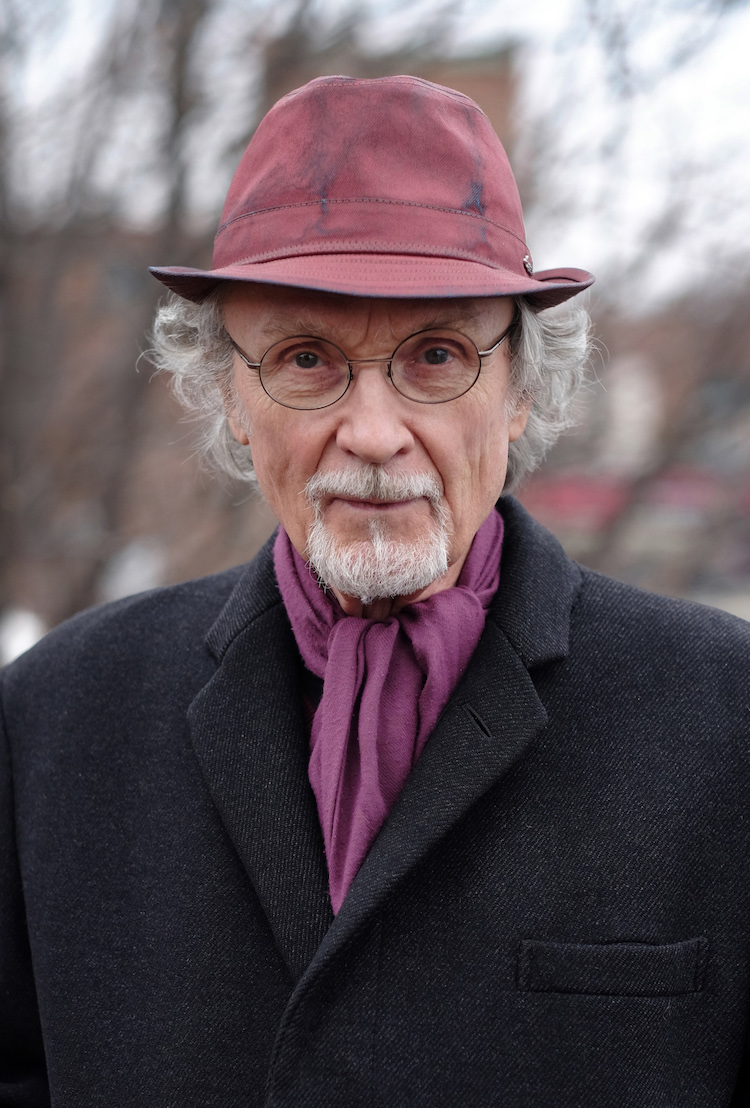

Midwestern Gothic staffer Giuliana Eggleston talked with author Robert Hellenga about his collection The Truth About Death and Other Stories, the connection between death and love, neutralizing the ‘eye-roll response’ in emotional scenes, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Giuliana Eggleston talked with author Robert Hellenga about his collection The Truth About Death and Other Stories, the connection between death and love, neutralizing the ‘eye-roll response’ in emotional scenes, and more.

**

Giuliana Eggleston: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Robert Hellenga: I was born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where my father was a commission merchant selling produce that came by boat from the Benton Harbor, MI, produce market, the largest farmer’s market in the US at the time. We spent our summers in Milwaukee, and the rest of the year in Three Oaks, Michigan — a town of 1800 people which, when I was growing up, had two drug stores, a large department store, several grocery stories, a good public library, a museum, a railroad station, a movie theater, and no Wal-Mart.

I attended the University of Michigan, got married, spent a year at The Queen’s University of Belfast, in Northern Ireland, then another year at the University of North Carolina, then Princeton, where I got my PhD. None of these places resonates for me as much as my two childhood home towns — Three Oaks and Milwaukee — and my present home town, Galesburg, Illinois. (And Florence, Italy, where my wife and our three daughters and I spent thirteen months in 1982-1983.)

GE: Your new collection of stories, The Truth About Death and Other Stories, takes place in Galesburg, Illinois and Rome, Italy, both places you have lived at some point in your life. How does where you’ve lived influence how you write about place, as well as other aspects of your writing?

RH: I see, in retrospect, that the Italians who worked for my father on the market in Milwaukee gave me a glimpse (and a taste) of a world very different from small town life in the Midwest (Three Oaks), a life that was more colorful, more pleasure-oriented. Sexual intercourse was regarded as the highest good. They also gave me a taste of la dolce far niente – the sweetness of doing nothing – something very different from the ceaseless striving to get ahead I’ve come to experience as normal.

This polarity has shaped my writing, but it wasn’t till our family spent a year in Florence that I began to think of myself as a Midwesterner. Margot, in The Sixteen Pleasures, and Woody, in The Fall of a Sparrow, are my first self-conscious Midwesterners. And both of them are able to hold their own and flourish in Italy, in a culture older and more cynical and (presumably) more sophisticated than their own.

Push comes to shove in a later novel, The Italian Lover, that brings these two characters together. Margot and Woody, now in their fifties, are in love. Margot wants Woody to stay in Italy, but Woody wants to go ‘home,’ to a small town in Illinois, and he wants Margot to go back to Illinois with him. She could, he suggests, work as a book conservator at the University of Iowa (an hour-and-a-half away). Margot chooses to stay in Florence, but she never gets over “the fear that her true home was elsewhere, that her real life – her true spiritual life – was not here in Italy, here at her work bench in her very own studio on Lungarno Guicciardini, or in her very own apartment in Piazza Santa Croce, but waiting for her back home, back in Chicago, back in the big house on Chambers St., waiting for her to take up where she’d left off.”

And speaking of houses: The houses we’ve lived in have become icons in my imagination — three in the Midwest and one in Italy: the big Victorian house we lived in in Galesburg, which we sold to our daughter and her husband (The Sixteen Pleasures, Philosophy Made Simple); the fantastic apartment in Borgo Pinti where we lived as a family for a year (The Sixteen Pleasures); the house in the woods near Monmouth that we owned for eleven years (Snakewoman of Little Egypt); and our present apartment (The Confessions of Frances Godwin) in Galesburg.

GE: The Truth About Death is true to its title, and follows two funeral directors meeting in Rome to prepare the body of a close relative. Did writing from the perspective of people who deal with death often change how you yourself view death? What was most difficult about dealing with this subject?

RH: Hildi, one of the POV characters in The Truth About Death, wants to go into the funeral business with her father because she thinks of the family funeral home as a place where the big questions get asked, if not answered. I like to write about death for the same reason, to address the big questions: On the one hand, death is perfectly natural; on the other hand, as Simon, Hildi’s father, reminds his daughter after they finish prepping the body of Simon’s father: Remember what Father Cochrane says at the beginning of every funeral: “Behold, I show unto you a mystery.” And then he puts his hand on his father’s forehead and says it again: “Behold, I show unto you a mystery.”

Did my own views change? I’ve come to believe, as Hildi does, that there was real value in the way that families used to prepare their dead. Hands-on experience. What would this value be? Hildi doesn’t think it’s something you can “tell.” Her father is skeptical, but in the end, when Hildi is killed in Rome, he holds her hand as the Italian undertaker washes her body. I have not done anything like this myself, but times are changing, and funeral customs are changing. Home funerals in which family members help prepare their dead are becoming easier to arrange.

The most difficult thing? Writing about the death of Olive, the dog. Olive’s death was based on the death of our own dog, Maya, who was diagnosed with liver cancer on a Monday and dead on Thursday. I’d like to read the Oliva passages aloud at a reading, but I can’t even read it to myself without tearing up. I think the special difficulty is that you can’t explain death to a dog. Of course you can’t really explain death to anyone, but with a person you can at least talk things over.

GE: The Truth About Death deals with love alongside of death. How do you see the two aspects of life as needing to be related?

RH: Death, or the prospect of death, is a lens that clarifies our relationships. It puts a lot of pressure on us to do what needs to be done, now. If you love someone, let them know now, before it’s too late. This is the sort of advice, as Margot points out in The Sixteen Pleasures, that you read in Ann Landers. It’s still good advice, however. The irony in The Sixteen Pleasures is that Margot’s mother was trying to tell her family, though we never find out exactly what she wanted to tell them because the tapes she made were blank. The tape recorder had malfunctioned.

It’s hard to do better than the following inscription, which appears (in Latin) in the death notice of Alexander Lenard, the man who translated Willie the Pooh into Latin: “Against the strength of love, you will find no herb. Against the strength of death, no herb grows in the garden.” This is what Woody finally puts on the tombstone of his daughter, who was killed in a terrorist bombing in Italy in 1982.

GE: Your writing seems to very naturally mimic life, drawing the reader into the stories and making them feel deeply, especially with the theme of death. What is your process like when crafting emotional scenes?

RH: On the one hand, I try not to hold anything back. On the other hand, I try to guard against the eye-rolling response. For example: in The Fall of a Sparrow Woody says to the terrorist (a young woman) who placed a bomb in the station in Bologna, the bomb that killed his daughter: “I have to love you because hating you is too hard.” I knew this line could be trouble. I tried to neutralize the eye-rolling response by including a lot of hard things in the scene, by having Woody almost strangle the woman, for example; by having the terrorist woman resemble Woody’s daughter; by trying to show that I was aware of all the complexities of this encounter. I took the line out several times and then put it back in. Several reviewers singled out this scene as one of the best in the book. But the New York Times reviewer, who in fact liked the book, looked up at this point and rolled his eyes: as the novel “winds down doctrine and philosophy prevail, and Woody, supposedly on the brink of self-knowledge, finds himself making pronouncements like, ‘I have to love you, because hating you is too hard.’” Oh well.

Ditto for all big emotional scenes, especially sex scenes. As a writer you put your erotic imagination out on the line for everyone to see. You don’t want your readers to roll their eyes. You need something that goes beyond a blow-by-blow description. Blow-by-blow descriptions are a dime a dozen. You have to give your readers a reason to want to imagine the scene that you’re inviting them to imagine, something beyond prurient interest. Someone has to be learning something, discovering something. And that means that you, as a writer, have to be learning and discovering something too. There’s no formula.

I didn’t hold back in the following passage from Snakewoman, for example, but I tried to provide a context that would ward off the eye-rolling response: After a mutually satisfying experience in bed Jackson, an anthropologist, asks Sunny, a biology student, “What just happened?” She gives him a biological account of her orgasm—pelvic area engorged with blood, muscle contractions, etc. “Why?” she asks. “What do you think happened?”

“You took me inside you,’ he said, ‘and devoured my seed when I was most vulnerable, and you were most triumphant. I explored your dark continent at my own risk. You lured me on. But because I survived the encounter, you will now share your great riches and power with me, because you love me.”

“It wasn’t really funny, but I started to laugh. ‘Is that what really happened?”

“‘That’s what really happened,” he said.

“I thought maybe he was right.”

Sun Times reviewer: “Talk about purple prose. But also talk about how skillfully Hellenga injects humor to reduce the swelling.”

GE: While it may be tempting – and even expected – to write about death with a sense of irony, The Truth About Death deals with it head on, avoiding the classic jokes and fully confronting the reality, emotional impact, and inevitability of death. Why did you choose to write about death this way, and was it difficult to resist the usual cop outs?

RH: Maybe because I’m a Midwesterner. Just kidding. Actually, I’m not just kidding. I’m thinking of a time I was doing research in Bologna. I joined the British Institute so I could use their library. The British Institute doesn’t stock any American novels, only British, so that’s what I read. Everything was ironic. Absolutely everything was undercut by irony: every generous impulse, every act of kindness, every moment of tenderness… After a while I couldn’t take it any more. I complained to the Italian friends I was living with, and Franco said: “That’s because England doesn’t count for much anymore.”

Irony isn’t always a cop-out of course. At its best it’s a way of showing that you’re aware of other ways of looking at whatever you’re looking at.

GE: In this collection of stories you revisit characters from a previous story, “Pockets of Silence” that appeared in The Chicago Tribune in 1989 as well as your debut novel Sixteen Pleasures in 1994. What made you decide to revisit this story in this most recent collection? What was it like continuing a story that started almost 30 years ago? Has time changed how you view the story?

RH: I’ve had more responses (letters and now emails) to this story than to anything else I’ve written. Maybe it’s because the ending took me completely by surprise. I couldn’t figure out what was going to be on the tape that Margot’s mother makes for her family as she’s dying. So I just stopped, left the tape blank.

And maybe the story stays with me because I’m like Margot: I still have unfinished business with my mother, who was a student at Knox College, where I taught English for almost forty years. Too late now.

GE: What’s next for you?

RH: I’m working on a novel about a rare book dealer. I’ve been thinking that I’m in over my head, though today I’m feeling better because I’ve figured out a way to tell part of the story from a woman’s POV. I feel more energized writing from a woman’s POV for a couple of reasons. One, we have three daughters and I’m used to looking at the world through their eyes. And two, women’s stories still have a kind of built-in urgency to them, a sense of breaking new ground, that appeals to me.

I don’t want to say much about it because everything is still in flux. I will say, however, that this summer I’ll be attending the Colorado Antiquarian Book Seminar in Colorado Springs — a week of intensive classes on the rare book business. We’ll see what happens.

**

Robert Hellenga grew up in Three Oaks, Michigan, a typical Midwestern small town, but spent summers in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where his father, a commission merchant with a seasonal business, handled produce that was shipped there from what was then the world’s largest farmers market, in Benton Harbor, Michigan. The men who worked for his father were almost all Italians, and in retrospect he sees that this is how he got his first sense of Italy as something opposed to small-town Midwestern Protestant culture — a theme that has shaped a lot of his writing.

He met his wife (Virginia) at the University of Michigan, spent the first year of their marriage in Belfast, Northern Ireland, spent a year in North Carolina, and started having children when he was in graduate school at Princeton.

Robert taught English literature at Knox College, in Galesburg, IL, from 1968 to about 2000. During his tenure at Knox he directed two programs for the Associated Colleges of the Midwest, one at the Newberry Library in Chicago and one in Florence, Italy, and spent a year at the University of Chicago on a National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship. He has spent quite a bit of time in Florence and Bologna, and in 2009 he and his wife spent six weeks in Verona, where Robert was a visiting writer at the University of Verona, and in 2012 they went to Rome for eight weeks.

Robert started writing fiction at Knox, which has a strong creative writing program, published his first story in 1973 and his first novel (after 39 rejections) in 1994. His most recent book is a collection of stories — The Truth About Death and Other Stories — and he is currently working on a novel about a rare book dealer who sets up shop in a small town on Lake Michigan.

September 29th, 2016 |

Midwestern Gothic staffer Lauren Stachew talked with author Lawrence Coates about his book The Goodbye House, how his time at sea prepared him to become an author, unsettling characters through specific settings, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Lauren Stachew talked with author Lawrence Coates about his book The Goodbye House, how his time at sea prepared him to become an author, unsettling characters through specific settings, and more.

**

Lauren Stachew: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Lawrence Coates: I’ve lived in Northwest Ohio since 2001, in the center of what was once the Great Black Swamp, and I’ve grown to understand Midwestern seasons and landscapes. I’ve also grown to understand something of the culture of this part of the world, in part through my creative writing students. The graduate program recruits nationally, and even attracts international students at times, but there is still a regional flavor to it. And the undergraduate program is made up almost entirely of Ohioans, so the stories I see and the discussions we have about them have given me insight into what it’s like to have roots here.

LS: You grew up in California, and all of your novels are set in Northern California. Now that you live in Bowling Green, Ohio, how did your perception of the Midwest change when you left the West Coast?

LC: It’s true that my novels are set in California, but I have written some short stories set in the Midwest, including “Bats,” which won the Barthelme Prize in Short Prose. I didn’t know much about the Midwest before moving here; I hadn’t spent much time in the region, outside of several trips to Chicago.

I’ve noticed one real contrast with the West since moving here. People who live in the Midwest seem to have settled near where they grew up, whereas people in California have come from around the world. And in the West, there seems to be a restlessness, more inclination to move. Perhaps it’s because of the landscape, the undeniable expanses of open and empty spaces in the West, and the dramatic mountain ranges that beckon people to move on, whereas the landscape here seems more cozy or confining.

And yet, the cultural understanding that one ought to belong and be content in a place can conceal a repressed feeling of estrangement. I think that’s one of the themes running through the work in Midwestern Gothic, and one of the reasons I enjoy the journal. In the short fiction I’ve set here, I’ve usually placed something strange or incongruous into a setting of utmost normality and tried to use that to explore what’s below the surface.

LS: Recently, you received an Ohio Arts Council Individual Excellence Award, as well as an Olscamp Research Award from BGSU. Congratulations! Could you tell us a bit more about these awards? How does this impact your current or future writing?

LC: Thank you. The Olscamp Research Award is really quite an honor. It’s the top research award at the university, and it’s given for scholarship or creative work over the previous three-year period. I applied for it because my work had received a lot of recognition during that span – to a certain extent, that’s just because the stars aligned, and I had a book out in 2012 and two books out in 2015. And the Ohio Arts Council recognition was also very gratifying. Ohio supports the arts in many ways, and I was very pleased to be named along with some other writers whose work I admire, such as BGSU alum Amy Gustine.

Some of my work is historical, and so the funds received from both awards will help finance travel to a couple of archives that are important to me. But what I really hope is that any awards and recognition I receive helps the work find readers. It’s more important to me that somebody reads and enjoys my work than to have a plaque on the wall.

LS: You spent four years as a Quartermaster in the Coast Guard and four more in the Merchant Marine. What led you to become a writer and professor?

LC: I did spend some eight years aboard a series of ships, from the North Atlantic to the South Pacific to the Indian Ocean. But I think I always wanted to be a writer, including during those years when I was at sea.

I was a sailor in the days before the Internet, before smartphones, before DVD’s, and the men I sailed with – and it was 95% men – were great readers and storytellers. I used to stand the midwatch, which means I was on the bridge of the ship between midnight and four a.m., and I remember those long hours under the stars out at sea hearing tales of every sort. And I met all kinds of people aboard ship, people I probably never would have encountered otherwise. On one ship, I bunked with a man who had sailed on ammo ships across the Atlantic during World War II and had been sunk by a U-boat. On another ship, I shared a forecastle with an ex-con who had been in prison for attempted murder, and yet when I knew him he wanted mainly to talk about his grandchildren. I sailed with many veterans of the Vietnam War who had never quite found their footing afterwards, and with a man who lost his job selling Winnebagos during the 1973 Oil Crisis, and then lost his marriage. We swapped books we liked. Lots of thrillers and detective stories, but also the stray Vonnegut novel. I remember one shipmate who loved Ray Bradbury and insisted I read Dandelion Wine. In many ways, my time at sea was great training for a writer.

Yet I wouldn’t have become a writer, I don’t think, unless I had decided at last to go to college and study literature. And once I began my studies, I found such a deep pleasure in it that, in some ways, I never left. For a time, I focused on contemporary Latin American Literature. In graduate school, I originally intended to write a dissertation on Don Quixote before deciding to change to a program at the University of Utah that would allow me to write a novel for my dissertation. In the course of my studies at Utah, I read and studied American Literature, and I found those themes in the novels of Melville and Faulkner that still form the core of my work.

I always enjoyed the teaching that was a part of graduate studies, and I’ve been fortunate to find a good position. I think it’s something of a privilege to teach in an MFA program, and I enjoy working with the talented young writers who come to Bowling Green for two years and then go on to write and publish fine works of fiction.

LS: Your most recent novel, The Goodbye House, is set in the aftermath of the early-2000s dot-com bust in San Jose, California, and follows the narratives of three characters whose lives are all affected by this changing landscape. What led you to write about this specific time in recent history?

LC: To some extent, writing about this time period grew naturally from my previous work. My first novel was entitled The Blossom Festival, and it took place in the region around San José in the twenties and thirties, just as the region was beginning to change from an agrarian, orchard-based economy to a more urban economy. The Santa Clara Valley, at one point, was known as The Valley of Heart’s Delight; now it’s known as Silicon Valley. And my first book tried to capture that time when things are beginning to change, even though the characters in the novel might be unaware of what is happening around them.

Setting a novel in the same region in the early 2000s let me explore again a time of great change. I was able to depict the suburban developments that had replaced the orchards, and also link up the last of the World War II generation with the new generation that was coming of age after computers had become commonplace – though a little before the rise of Facebook, Snapchat, and smartphones.

2003, specifically, meant that the novel was set not only in the aftermath of the dot-com bust, but also in the aftermath of 9/11. It was a time when many established verities were being called into question, and that allowed me to unsettle my characters in ways that forced them to act and reveal themselves.

I know that many works of fiction are set in a somewhat undefined present, but I prefer to place novels in specific years because I want to show that the characters are part of a larger world, and that the larger world influences their lives, even though they might not realize it.

LS: You’ve spent nearly twenty years teaching creative writing, both as a professor and a director of the MFA Program at Bowling Green State University. How has the experience of teaching taught you about your own writing?

LC: Teaching creative writing, particularly at the graduate level, has taught me to be very conscious of craft. Because I am frequently reading and responding to works that are in process, I’ve had to develop a vocabulary to describe what is being workshopped. And that vocabulary of point of view, dramatic irony, narrative arcs, the sense of an ending, has inevitably come into my own composition process.

Let me say something briefly about teaching that comes from John Gardner’s On Becoming a Novelist. One of the marks of a bad workshop, he says, is that the teacher tries to “coerce his students into writing as he himself writes.” So when I say I’ve developed a vocabulary to describe work, I don’t intend for that description to be a judgment that something is good or bad. I look at it as a way to help young writers see what the work is doing and allow them to understand for themselves whether it is fulfilling their intent. I think, in the past, I was more judgmental in workshops, and I hope I’ve left that behind.

But to your question – being aware of craft has allowed me to consciously choose an aesthetic stance for a particular work. One of my literary heroes is Virginia Woolf, in part because she was a writer who seemed willing to reinvent herself for each work. So the writer who created To the Lighthouse or The Waves, those shimmering works that depict the individual consciousness of characters, could also create Orlando, a crazy novel that takes place over several hundred years and has a narrative voice not too dissimilar from that used by Henry Fielding in Tom Jones.

In my own work, I chose a more distant omniscient voice for The Blossom Festival, suitable to the epic sweep of the book. In The Master of Monterey, the narrative voice is clearly also a character, sometimes addressing the reader directly. In Camp Olvido, the point of view is more objective, painterly, without judgment, suitable to the deep moral ambiguity at the heart of the book. The Goodbye House, on the other hand, is a more comic novel, and the narrative voice feels free to comment on the characters’ flaws and foibles. It’s a point of view I’ve sometimes called “smart ass omniscience,” very good for comic writing.

So teaching has made me very conscious of craft, and I hope that has served me well in the works I’ve published.

LS: You mentioned in a previous interview that you write on a manual typewriter. What made you choose this method, and why do you feel it’s a better option than the modern computer?

LC: Using a manual typewriter is partly just a personal preference. I like the feel of the keys, and I like the sound of the type hitting the platen. And there’s something nice about a pile of pages that grows a little taller, day by day. It’s much more satisfying than seeing the size of your file go from 48 KB to 52 KB.

However, I also like the fact that I never lose a word or a phrase. There is no delete key. When I type something that I want to revise, I cross it out in pen and continue typing. Then, during revision, my initial impulse is there and present. I tend to complete a draft of a chapter and then enter it into the computer from the typescript. So re-typing the entire manuscript also becomes a part of my revision process.

It’s not something that’s right for everyone, though I sometimes mention that Cormac McCarthy wrote Blood Meridian and all his other works on a portable Olivetti that he bought for fifty dollars at a thrift store. That seems to get people’s attention.

LS: Which author or authors have had the most influence on your writing?

LC: At the top of any list of authors important to me would be William Faulkner. His deep engagement with a particular region and the way the burden of history weighs upon the lives of characters remains a north star for me. Gabriel García Márquez, a writer himself influenced by Faulkner’s work, has been important for me. I decided to learn Spanish in part because of wanting to read One Hundred Years of Solitude in the original. Toni Morrison is another author who consciously places her stories within a historical context that haunts her characters – sometimes literally, as in Beloved.

Ernest Hemingway famously said that all American literature comes from one book by Mark Twain called Huckleberry Finn. I couldn’t disagree more. There has always been a counter-current to Twain in American literature, exemplified by the strangeness of writers like Hawthorne and Melville who found it impossible to represent America through the narrow canons of European realism. And I hope to write work that shares some quality of strangeness with the writers I most admire.

LS: What’s next for you?

LC: I’m working on a novel that takes place over fifty years in an invented city that hovers on the border between Silicon Valley and the Great Central Valley of California. There will be ghosts. That’s about all I can say for now.

**

Lawrence Coates has published five books, most recently The Goodbye House, a novel set amid the housing tracts of San Jose in the aftermath of the first dot com bust and the attacks of 9/11, and Camp Olvido, a novella set in a labor camp in California’s Great Central Valley. His work has been recognized with the Western States Book Award in Fiction, the Donald Barthelme Prize in Short Prose, the Miami University Press Novella Prize, an Ohio Arts Council Individual Excellence Award, and a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship in Fiction. He is currently a professor of creative writing at Bowling Green State University.

September 22nd, 2016 |

Midwestern Gothic staffer Lauren Stachew talked with author Martin Seay about his book The Mirror Thief, coordinating three separate stories into one novel, encouraging empathetic openness through fiction, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Lauren Stachew talked with author Martin Seay about his book The Mirror Thief, coordinating three separate stories into one novel, encouraging empathetic openness through fiction, and more.

**

Lauren Stachew: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Martin Seay: I’m a relative newcomer to the Midwest, having grown up in the western suburbs of Houston. (Specifically in the town of Katy; “the western suburbs of Houston” could plausibly describe an area the size of Connecticut.) My spouse Kathleen Rooney and I bounced around the country for a while — Washington DC, Boston, Provincetown, Tacoma, WA — but we’ve lived in the Edgewater neighborhood on the far north side of Chicago since 2007. Kathleen grew up in the Woodridge–Downers Grove area, and her family hails from Nebraska, so she’s credentialed as a native Midwesterner.

Regional identity — and Midwestern identity specifically — is something that I think about a lot. This is totally unscientific on my part, but I can’t help but think that there’s something in the tension between the natural and built environments in every region that affects the assumptions and the expectations of the people who grow up there, in ways that are so fundamental as to be nearly invisible. I’ve often been struck by how completely domesticated the Midwestern landscape is: just about every square inch of dry land has been shaped and reshaped by human habitation for so long that every space feels like a social space, and therefore one always feels as though one is within the bounds of some society or another here. (In the Pacific Northwest, by contrast, it never felt like we were really part of a society — or at least it felt as though society was something that everyone could exit at will and without much of a fuss.)

LS: In what ways do you feel that living in the Midwest – specifically Chicago – have influenced your writing?

MS: I should confess that the vast majority of my recently-published novel was written before I arrived in Chicago. Since I’ve been living here, most of the writing I’ve done has been essays and criticism of various sorts. (I don’t think this has been a direct consequence of living in Chicago, but rather just of having a full-time office job and an hour-long commute.) I’m about to return to fiction after quite a bit of time away, and I’m interested to see the effect that Chicago has on whatever I end up doing.

One quality of Chicago that has had a significant impact on Kathleen’s and my lives is the vibrancy and openness of the literary scene here, which overlaps in unforced, organic, mutually-beneficial ways with the theater scene, the music scene, the dance scene, the comedy scene, the art scene, etc., and produces a ton of interesting and hard-to-categorize work that lands in the spaces between those more recognizable forms. Beyond the fact that living here has made us aware of a bunch of cool stuff, we have also met a bunch of great people who are very receptive to each other’s pursuits and supportive of each other in creative, professional, and personal terms.

In some ways the fact that many of the city’s most prominent institutions seem to be in danger of collapsing — or of not collapsing, depending on the institution — seems to empower and inspire activities at the small, nimble, independent, subcultural level, which is cool. I think most of us would happily swap some of this great art for a city that’s more just and more functional, though.

LS: Your debut novel, The Mirror Thief, weaves together three separate stories into one novel, all set in three different versions of Venice. Some reviewers have called this skill “almost miraculous.” How did you manage these various threads as you were writing? Did you draw out maps or charts?

MS: It helped a lot that I had the structure first. Before I had any characters, or much in the way of a plot, I knew I would be writing a narrative split evenly between Renaissance Venice, Beat-era Venice Beach, and more-or-less present-day Las Vegas. I also knew that certain locations or people would appear: the Venetian casino, the Guggenheim Hermitage Museum, and a flooded Mormon town in the 2003 chapters; Alexander Trocchi, Lawrence Lipton, and the Venice West Café in 1958; and Giambattista della Porta, Giordano Bruno, a glass factory, and a bookstore in 1592. I came up with plots that would connect all these elements, and then I came up with characters who could follow the paths I had laid out. Consequently I always knew where I was going (although I was a little foggy on how long it would take me to get there).

I outlined backstory more rigorously than I did the three main storylines that run through the book. I definitely used outlines to keep myself straight on the action taking place in the narrative present, but I tried to be sparing with them; I didn’t want the plot to become too functional, or too much of a glide path for the characters. All my best discoveries came as a result of slowing myself down, not speeding myself up.

LS: What made you choose Venice as the unifying “setting” for this novel?

MS: Venice came first: I knew I wanted to write about Venice before I knew anything else about the novel, or even that it was a novel. I had been to Venice for a couple of days in the late ’90s while doing the post-collegiate-tour-of-Europe thing, and it stayed in my head as a place I that wanted to use as a subject and a setting. (I also knew, of course, that a bunch of people had beaten me to the punch—including heavy hitters like Henry James, Thomas Mann, Daphne du Maurier, and my esteemed former teacher Jane Alison — but I decided to think of this as more of an advantage than a problem.)

A lot of things about the city fascinated me (and still do) — aspects that make it different from any other place, and contrast with other European cities in interesting ways: the primacy of canals over streets, the near-total absence of fortifications, and the distinctively light, permeable, curvilinear nature of the built environment, to name a few. The one fact I learned about Venice during my first visit that struck me the most is that it is not, strictly speaking, built on islands: most of its present-day land was constructed by driving masses of wooden pilings through the lagoon’s sandy bottom into the clay beneath, and almost all of its churches, palaces, squares, and streets are (somewhat tenuously) supported by these pilings. The city is literally built on the water. The blankness of the canvas that the Venetian engineers were working with and the necessary deliberateness of their methods — along with Venice’s complex and ambiguous thousand-year history as a functioning republic — led me to think of it as the city that’s most purely expressive of the will and values of the community that created it: a city grown in a Petri dish, basically. Therefore it seemed like a good lens through which to view other cities, and other human undertakings.

LS: Many reviewers have drawn similarities in your novel to the writings of authors such as David Mitchell, Umberto Eco, and Italo Calvino. Were any of these authors inspirations to you?

MS: Invisible Cities definitely was; I borrowed a passage from it — a fairly cryptic and mind-blowing exchange between Kublai Khan and Marco Polo — as the epigraph of my book. But that’s the only thing of Calvino’s that I’ve read in its entirety: I picked it up shortly after I started The Mirror Thief because I thought it would help me get my head straight about Venice from a conceptual and metaphorical standpoint, which it did. I was drawn to it both because of its unusual engagement with Venice as a subject and because I had recently been interested in the Oulipo, the mostly-European group of avant-garde writers who used various restrictions and quasi-mathematical structures as strategies for generating literature; Invisible Cities comes from the period of Calvino’s participation in the group. (The Mirror Thief didn’t end up being very Oulipian; the only real restriction is the fact that I never used the word “Venice” — or any form of it: no venetian blinds, no Venezuela — in the book. Oulipian novels like Invisible Cities and Harry Mathews’ under-appreciated Cigarettes also inspired me to deploy certain recurring images or concepts as generative and organizing devices — mirrors, mosaics, excrement, pirates, pelicans, mercury, Mercury, the various stages of the alchemists’ Great Work, etc. — but my use of them was not remotely rigorous enough to meet Oulipian standards.)

So far as Mitchell and Eco go, I really enjoyed Cloud Atlas, but it wasn’t an influence: I didn’t read it until after I had finished the manuscript of The Mirror Thief, and it’s still the only thing of Mitchell’s that I’ve read. This is maybe going to sound lame, but although I have definitely been strongly influenced by my idea of what an Umberto Eco novel is like, I’ve never read one: I have copies of Foucault’s Pendulum and The Name of the Rose that I’ve been moving from apartment to apartment with me for years, but I’ve never read either, despite several attempts.

The novels that were probably the biggest influences on The Mirror Thief — to my way of thinking, anyway — are All the Pretty Horses by Cormac McCarthy, My Name Is Red by Orhan Pamuk, The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle by Haruki Murakami, Cat’s Eye by Margaret Atwood, and The Big Sleep by Raymond Chandler. From Hell by Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell ended up being something I thought about a lot while I was writing; so did House of Leaves by Mark Z. Danielewski. Books by Elmore Leonard, Dennis Lehane, and Alan Furst helped me figure out the genre mechanics of the 2003 and 1592 sections. To nail down some of the cadences and the lexicon of the 1592 sections, I also reread a fair amount of Shakespeare. A few nonfiction books were very inspirational, particularly Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of the Twentieth Century by Greil Marcus, The Optical Unconscious by Rosalind E. Krauss, and Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters by the painter David Hockney, which sounds like an instructional book but isn’t.

LS: You spent nearly six years writing The Mirror Thief – what was the most difficult part of the writing process for you?

MS: The most difficult and rewarding part of the process was figuring out the three main characters: working out their backstories, but also and especially developing an understanding of how they would uniquely perceive the world.

This is not something that comes easily for me: I’m a concept-driven writer, and plot and character tend to show up late in the game. I reached a point early on where I needed to pretty much stop writing and just spend a couple of years trying to imaginatively inhabit the fictional world of the book, thinking really hard about my characters’ embodied experience of that world: to consider, for instance, not only what walking down the Las Vegas Strip in March of 2003 would have been like, but specifically what it would have been like for a 39-year-old partially-disabled retired U.S. Marine who spent the previous night sleeping in a chair at Philadelphia International Airport.

Of the many great things about fiction, I think one of the best is its capacity to encourage empathetic openness to others, and to do so by modelling that openness. I wanted to honor that capacity by taking the responsibility of depicting my imaginary people seriously.

LS: What advice would you give to authors who are trying to have their first novel published?

MS: If you can keep your manuscript under 700 manuscript pages, I recommend doing so. Trust me on this one.

But seriously…I should probably mention that The Mirror Thief took me a little under six years to write, and a little over seven years to find a publisher for. This was due in large part to the fact that I was circulating the manuscript in the midst of a recession that clobbered the publishing industry, but there’s really never going to be a time when the major trade houses are going to be tripping over each other to hand out seven-figure advances to unknowns with really long first novels, even if those novels do include swordfights (which, for the record, mine does).

I’m hardly an expert on the publishing industry based on my limited and rather atypical experience, so I can’t provide much in the way of practical advice beyond one very general recommendation: it’s a good idea to develop strategies for keeping your head straight when you move from a process in which you have total, godlike control (i.e. the process of writing) to one in which you have approximately zero control (the process of seeking publication). More specifically, I’d suggest that your strength in navigating the latter process will come from your rigor during the former process: you should be damn sure that you’ve written the book you wanted to write, because confidence in your manuscript will sustain you through long stretches of radio silence and help you make productive use of the feedback you receive from agents and editors.

LS: What’s next for you?

MS: Great question! I have a few ideas for new novels that I’m playing around with; if past experience is any guide, I’ll need to live with them awhile before I know which I’ll pursue. In the meantime, I have several criticism projects — writing on music and film — that I’m excited to work on. I’m very fortunate that The Mirror Thief has gotten quite a bit of positive attention, and it seems to be bringing some interesting opportunities my way. So far it’s been rewarding to just remain open to whatever comes along, and enjoy it while it lasts.

**

Martin Seay’s first novel, The Mirror Thief, was released by Melville House in May. Other writing has appeared recently in Electric Literature, Lit Hub, Publishers Weekly, MAKE, and The Believer. Originally from Texas, he lives in Chicago with his spouse, the writer Kathleen Rooney.

September 15th, 2016 |

Midwestern Gothic staffer Lauren Stachew talked with author Julie Lawson Timmer about her novel Untethered, complicated familial bonds, juxtaposed sentiments toward one’s Midwestern hometown, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Lauren Stachew talked with author Julie Lawson Timmer about her novel Untethered, complicated familial bonds, juxtaposed sentiments toward one’s Midwestern hometown, and more.

**

Lauren Stachew: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Julie Lawson Timmer: I live here! Since 1998, I’ve lived in Michigan – in Dearborn for the first 2 years and in Ann Arbor for the rest.

LS: Your most recent novel, Untethered, grapples with questions about family bonds, loss, and the rights and limitations of laws. How did you find yourself drawn to these questions, and what made you feel the need to explore them in the form of a novel?

JLT: In Untethered, the main character, Char, is a stepmom. Char’s husband dies before the book begins, and we’re left with the question of who Char’s stepdaughter, Allie, should live with: Char, who has raised Allie full-time for the past 5 years, or Allie’s bio mom, Lindy, who lives across the country and has never been all that interested in parenting. The trick is that Char has no legal rights to Allie – most stepmoms don’t have legal rights to their stepchildren – while Lindy now has sole rights. I was drawn to this question because I’m a stepmom myself, and it has often occurred to me that if something were to happen to my husband, I might never see my stepchildren again.

The other legal/family question in Untethered deals with adoption and “rehoming,” a practice where adoptive parents give their adopted child away to strangers – often over the Internet, with no legal oversight and no background checks. I read a Reuters article about rehoming a few years ago and was shocked to hear this is happening in the United States, and with some regularity. I wanted to explore that in a novel in part to open people’s eyes to this practice, which many are unaware of.

LS: Do you feel that the novel’s Midwestern setting is intrinsic to the story? What made you choose to set the story in Michigan?

JLT: Yes, I do feel that in Untethered, the setting is intrinsic to the story. One of the characters is an automotive engineer, so Michigan was a natural choice. Another character chose to move away and has a certain amount of derision for Michigan, the automotive industry, the weather, while those characters who stayed are proud to live here. I think there’s an element of that in many people’s lives – those who love a place and choose to stay, and those who can’t wait to get as far away as possible. I think that element is pervasive in a place like Michigan, which is auto industry heavy and experiences some extreme weather in the winter; those are the kinds of things some people want to escape from, while others are proud of Michigan for the fact that it has the auto industry and a northern feel.

LS: Your first novel, Five Days Left, features a character who is a lawyer, and you yourself are a lawyer as well. How much of your own life and personal experiences inform your writing? Do you find this is something you gravitate towards intentionally, or does it tend to appear naturally in your writing process?