Interview: Eric Shonkwiler

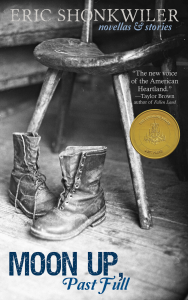

MG staffer Hannah Bates talked with author Eric Shonkwiler about his new collection Moon Up, Past Full, his Ohioan roots, what draws him to Dystopian fiction, and more.

MG staffer Hannah Bates talked with author Eric Shonkwiler about his new collection Moon Up, Past Full, his Ohioan roots, what draws him to Dystopian fiction, and more.

**

Hannah Bates: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Eric Shonkwiler: Born and raised. I lived in Ohio until I went off to grad school in California. I’ve since returned to and fled Ohio several times, so the Midwest is pretty clearly an inextricable part of me.

HB: Your new collection of novellas and short stories, Moon Up, Past Full, is dedicated to your mother. How has she inspired you in writing this collection?

ES: My mother is, rather luckily, not directly related to anything in the collection, but she did relate to me some family lore that inspired a story and a novella in it. When pulling the collection together, I realized that most of these stories have families at their heart—which I was a bit surprised by—so of course she’s been an influence in some fashion there, as well.

HB: Many of your stories take place in quintessential rural settings: dirt roads, farmhouses and cornfields. Is this a nod to your Ohioan roots? Why else is rural America attractive as a setting?

ES: Nearly every story in this book is set in Ohio, whether that’s clear or not. I think the importance of these locations is impossible to overstate—the places are the stories. It’s what I know best, and it’s what most of my ideas lead to. I think to say these settings are attractive is to subvert my process; the setting comes first. It would be impossible to lift a story and place it elsewhere, for me. It would be an entirely different story.

HB: Your debut novel Above All Men is futuristic in its depiction of dystopian America. What draws you to write dystopian fiction? Does the genre allow for commentary that contemporary settings do not?

ES: Above All Men began with the desire to blow up contemporary issues and present them in a realistic, fatalistic fashion. I wanted to say, “This is what could be coming down the pike.” Roiling in that message was a fascination with apocalypses of all forms, and wanting to show a unique, slow-burn ending of the world as we know it. The genre was freeing, for me, because it gives you a big sandbox to play with. You get to, and have to, decide what’s happened, what’s come between the world we know and this one. That lets you tuck a lot into a story that you otherwise couldn’t. Moon Up has a slightly dystopian bent, here and there, with stories like “GO21” and “Last Snow.” The former depicts the fallout of an asteroid breaking apart over America, and the latter is a near-future family story, dealing with the effects of global warming.

HB: Where does your fascination with the military come from? Does writing about veterans speak to larger themes about what it means to be an American?

ES: It originates from a chip on my shoulder for not having served, myself, and having peers and a close relative who had. I thought that if I didn’t serve, I could at least dedicate work to the people who did. It’s important to me to acknowledge the people who have served—no matter your personal politics—because they quickly become, on return, a second-class. That’s baffling to me. All the flags and yellow ribbons in the country don’t add up to true care. In that way, yes, it does speak to larger themes of America, and being American.

HB: Your writing withholds no details as to what everyday Midwestern life can look like: even very common activities (like hunting, pizza parties, driving down the road) have a place in Moon Up, Past Full. Why was it important to you to create a work of literature that celebrates the everyday?

HB: Your writing withholds no details as to what everyday Midwestern life can look like: even very common activities (like hunting, pizza parties, driving down the road) have a place in Moon Up, Past Full. Why was it important to you to create a work of literature that celebrates the everyday?

ES: I don’t know that this was a terribly conscious decision. Every day starts as “the everyday,” and then becomes or doesn’t become one you remember. These events are the meat of life. To ignore that and to ignore the stories of these same “everyday people” is to ask that reader and writer create a deeper fiction, one that eschews the vitality and potential of reality. There’s a place for that kind of fiction, but it’s not in my writing.

HB: In your writing you don’t use quotation marks for dialogue. What is the effect of this, and how does it enhance your writing?

ES: For Moon Up, Past Full in particular, a decision had to be made regarding the consistency of the text. Some stories originally included quotation marks, and some did not. The publisher and I agreed that to go back and forth was irritating, so the decision was made to cut all marks, which is in keeping with the larger portion of my writing, and style. I’ve found that, in general, omitting quotation marks allows for a particular look to the page, which, while minor, changes the interpretation of the text itself—it takes on a leaner feel. It also makes the reader pay closer attention, which I think is useful for writers of subtlety.

HB: What’s next for you?

ES: I’ve got a new novel coming out next year called 8th Street Power & Light, edits of which will soon take up most of my time. Once that’s squared away, I’ll start editing a novel that I just finished this summer, about a Great Depression-era family. I’d like to have that in good shape by the time the new novel drops, so I can begin the process all over again.

**

Eric Shonkwiler is the author of the Luminaire Award for Best Prose-winning story collection Moon Up, Past Full (Alternating Current, 2015), and the novel Above All Men (MG Press, 2014), which won the Coil Book Award for Best Book and was chosen as a Midwest Connections Pick by the Midwest Independent Booksellers Association. He has had writing appear in Los Angeles Review of Books, The Millions, The Lit Pub, and elsewhere. He was born and raised in Ohio, received his MFA from University of California-Riverside, and has lived and worked in every contiguous U.S. time zone.