Interview: Rachel Jamison Webster

Midwestern Gothic staffer Rachel Hurwitz talked with poet Rachel Jamison Webster about learning by teaching, writing on the El, expressing herself on different wavelengths, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Rachel Hurwitz talked with poet Rachel Jamison Webster about learning by teaching, writing on the El, expressing herself on different wavelengths, and more.

**

Rachel Hurwitz: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Rachel Jamison Webster: Well, I’m definitely a Midwesterner–in personality and history. I grew up in Northeastern Ohio and I have spent most of my adulthood in Chicago. My favorite thing about the Midwest is probably its people.There is a down-to-earth approachability here that I like, a lack of pretense–and a friendliness.

RH: How has living and teaching in Chicago influenced the style or content of your writing?

RJW: I used to write more overtly urban poems when I first moved here. I was so excited to be in Chicago that I would ride the El for hours with nowhere to go, just to look around and write in my notebook. I had come from a very small town, and I was elated by the diversity of people, the unending thrum of urban life. I loved the way I’d get quick glimpses of graffitied brick, geraniums on a sill, someone making dinner in her bra, kids playing basketball–all from the window of the El. And I loved watching people on the train and listening to their conversations.

RH: Encouraging youth to write seems to be an important part of your life, since you have edited two anthologies of writing by young adults, “Alchemy” (2001) and “Paper Atrium” (2004), as well as founded writing workshops for homeless youth in Oregon. What led you to become involved in this type of work?

RJW: I am someone who has always learned best by teaching, and I have always taught best by sharing the experience with my students. As an undergraduate in Portland, I was writing a thesis on Adrienne Rich, which made me want to widen poetry’s subject matter and participants, to reach more diverse, “under–served” audiences. And this led me to examine research on the profoundly activating effects of making art. I realized that people who are making art, including writing, have a way to externalize pain and trauma and transcend it, and then contribute to a more conscious society. Writing and art–making build confidence and agency in the creator, and then allow the artist to give back, to instruct and improve society. I first put these ideas into action by creating writing workshops with homeless youth in Portland. These kids had been in gangs or in other abusive situations, and all had been kicked out of public school. They taught me more than I taught them, I’m sure. And even though their situations were so dire, they did not make me feel that this work was frivolous or irrelevant, but necessary, even urgent, because they really needed to know that their voices and experiences mattered. When I moved to Chicago, I was able to put these ideas into action through the visionary program Gallery 37–conceived of by Lois Weisberg and developed by Maggie Daley–which offered arts “apprenticeships” to thousands of urban youth. First, I was PR Coordinator for the program, then I helped to grow the literary arts division, Words 37, then I taught with Words 37 and and co-edited the anthologies, the content of which was all selected by the teens themselves. I saw kids’ lives change dramatically because they were given the time and space to create, and because their creations and voices were taken seriously.

RH: Similarly, what effect have these experiences had on your own career as an author?

RJW: They helped me to respect and celebrate the range and diversity of talent that we have all around us. And teaching can exist in a kind of symbiotic relationship to writing. My students’ interests and conversations remind me that this work matters.

RH: As a teacher, is there any one piece of advice or guidance that you normally give to your students?

RJW: I encourage them to free–write–that is, write for 8-15 minutes every day with no judgments and no requirements for a product. Once you begin to make that space for yourself–a space of safety, catharsis, observation and imagination–you will be amazed by what you can create in a little margin of time that is customarily wasted checking FB or something. You’ll never be blocked because you’ll have a notebook full of “starts,” and you’ll be practicing one of those essential paradoxes of writing–taking yourself seriously enough to notice and verbalize your inner life, but not so seriously that you’re getting fixed in the story you’re telling about yourself. Everything there can be made into something more artful, more imaginative and vivid. You begin with the raw material of life, and then you create, evolve, expand.

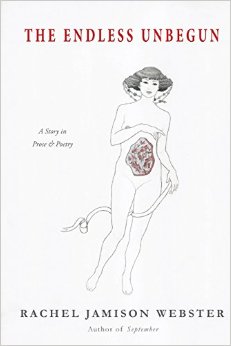

RH: Your latest publication, The Endless Unbegun is a hybrid novel told through poetry and prose that takes place throughout many centuries. Where did the inspiration for this complex work arise?

RH: Your latest publication, The Endless Unbegun is a hybrid novel told through poetry and prose that takes place throughout many centuries. Where did the inspiration for this complex work arise?

RJW: Well, I guess it began with the awareness of wavelengths. I realized that I was living and expressing myself on different wavelengths depending on who I was with. There was a way of relating to others that was essentially prosaic–that is, adhering to a collective consciousness and concerned with the objects and furniture of this visible world. And there was a way of relating that was more poetic–timeless, atmospheric and soulful. I wanted to write a love story that had a prose frame–the way our lives have their frames in ordinary life–that would somehow break though its prosaic–ness into a poetic center. I was writing this at the beginning of online dating and watching as a transactional model overtook the world of relationship. We were creating this consumerist mode for relationships, while longing to touch something more mysterious, numinous and powerful. I had experienced my own release from collectivity, an opening to a new wavelength of higher awareness–and I realized that, for me, the most poetic moments, like the most profound loves, are echoey. They seem accompanied by a kind of recognition, like the moment, or the poem, has happened before or will happen again. So I began to write this story that had happened again and again, through many lifetimes, in a kind of eternal return.

RH: Consequently, how did you balance the multiple forms and storylines present within The Endless Unbegun?

RJW: There is a lot going on! I am glad that they feel balanced to you. I think this book requires a good reader–that is, a reader who trusts the emotional spaces and associative logic at its heart. A reader who trusts herself and has her own inner life to refer to. I usually overwrite a book and then whittle it back as I try to imagine how much a reader could take in. I tried to use the form–with epitaphs beginning each section–to provide kind of frame for the reader, and then give a little space between poems and voices.

RH: Do you have a situation or place that you find most conducive for writing your poetry?

RJW: I need a somewhat quiet, meditative space to write poetry. Prose is a little more above-board for me, but poetry often unfurls rapidly or oddly. I’ll be sitting at my desk chanting the poem and it’s weird to try to do that in public. Usually I write at home. But I find that every project comes with its own demands. I wrote the entire first draft of my next book outside on Lakota land, beside sagebrush and streams. And I wrote the entire first draft of The Endless Unbegun longhand in a big blue hardcover blank book that my friend had sent me–it had the misleading title The Castles of Japan. I had a dream that I was flying through the air holding a blue book in front of me–like a kickboard–and then this blank book arrived the next week in the mail, so I got to work filling it up. The whole time, I sensed that I was trying to loft myself out of the more grounded work I had been doing into something more imaginative, mystical and true. Then I culled and revised it for the next seven years! So my process is not wholly whimsical. But it does begin that way, with some hunch, synchronicity, or wonder.

RH: What’s next for you?

RJW: I just finished a book that is a kind of “Ghost Dance,” a gathering of prose poems written in the voices of Lakota ancestors who participated in the Ghost Dances of 1890 and then were murdered by US soldiers at Wounded Knee. These poems are interspersed with found poems “mined” from John McPhee’s book about geology, Annals of the Former World. The two kinds of poems represent two different sensibilities–the mining, empire-building mind that sees the earth as a means to an end (a place to drill for resources), and the mind that sees the earth as a beloved, sacred relation. I’ve been writing this off and on for several years and have just returned from the Pine Ridge Reservation, where I’ve been doing some final research and meeting with Lakota elders. This is a tragic, maddening story, but there is beauty and wisdom in these voices, and irony in the found poems, and I am really excited to share them. I think that this book will be published in late 2016 or early 2017.

**

Rachel Jamison Webster is author of the book of poetry September (Northwestern University Press 2013) and the cross-genre book of poetry and prose, The Endless Unbegun (Twelve Winters Press 2015) and two chapbooks, The Blue Grotto and Hazel and the Mirror, both from Dancing Girl Press. Rachel has won awards from the Academy of American Poets, the Poetry Foundation and the Poetry Center of Chicago and has published poems and essays in many journals and anthologies, including “Tin House,” “Poetry,” “The Southern Review,” “The Paris Review” and “Labor Day: Birth Stories from Today’s Best Women Writers” (FSG 2014). She directs the Creative Writing Program at Northwestern University. You can read some of her work at www.racheljamisonwebster.com.