Interview: Margo Jefferson

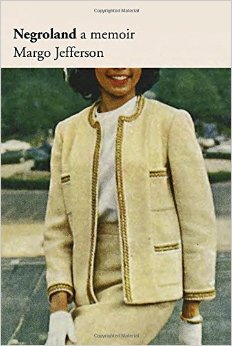

Midwestern Gothic staffer Giuliana Eggleston talked with author Margo Jefferson about her novel Negroland: A Memoir, changing perspective, the most difficult writing she has ever done, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Giuliana Eggleston talked with author Margo Jefferson about her novel Negroland: A Memoir, changing perspective, the most difficult writing she has ever done, and more.

**

Giuliana Eggleston: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Margo Jefferson: I grew up in Chicago, as did my mother.

GE: Do you feel that being from a large city like Chicago has influenced your writing? If so, how?

MJ: I was always grateful to be from a city that mattered historically. A place of consequence. If you look at Chicago squarely you’re looking at certain truths about America: the systemic vices & cruelties; the art (innovative, insistent); the self-consciousness about one’s importance, one’s ranking, one’s “place” in the world. And like many Midwesterners I yearned to go East, live in New York! Once I settled there though, I was glad not to have grown up there. New Yorkers can have the provinciality that comes from feeling they were always at the center of what counted culturally. I felt (I told myself) that being from the Midwest had left me open to influences that weren’t always so culturally sanctified.

GE: In your new novel Negroland: A Memoir, you often address the reader, telling them to “keep a close watch” or announcing a change in perspective. What made you decide on this style of narration? How has it facilitated you in writing a memoir?

MJ: I needed to find a form (forms) that would document and dramatize the perspective shifts that were essential to my Negroland upbringing. I was taught how to perform class, race, gender in a variety of settings, to meet certain demands, to thwart certain demands, to mediate conflicting demands. And I needed to show how the internal self, my particular psyche responded; what its strategies were. So the audience, the readers needed to be made constantly aware of all these performance requirements, external and internal. I don’t think I could have written a memoir otherwise. I had to be faithful to the truth of fragments, contradictions, constant pressure and constant shifts of consciousness.

GE: What was the most challenging part about writing a memoir? Was it more or less challenging than other writing you’ve done? How so?

MJ: This was WITHOUT A DOUBT the most difficult writing I’ve ever done. For one thing, as I confess right off, I’d been brought up NOT to reveal vulnerabilities and mistakes to the larger world, lest they reflect badly on black people as a whole. So I had to make that perspective part of my revelation. And that revelation, that story, was personal, historical and cultural. I always thought of the book as a cultural memoir. Finding the relations, the symmetries and asymmetries between self, history and culture was my struggle.

GE: What inspired you to write a memoir? Was it something you thought about for a while?

MJ: Yes, I’d thought about it, and taken scattered notes, and asked friends and relatives questions for quite a while. I started to focus after I’d finished the Michael Jackson book and left The New York Times. What’s next, I asked myself? How do I do what I haven’t yet done? I was excited about trying things technically – scenes, dialogue, confession, collage – that hadn’t been part of my writing as a critic.

GE: You were a theatre critic for The New York Times. Has that affected how you receive critiques of your own writing?

MJ: Actually, I was a book reviewer much longer than I was a theater critic. I can’t pretend that I’m not as persnickety and self-protective as any other writer, but there is a part of me that can detach and analyze the formal elements of any review. Whether it’s books or theater, we critics tend to play the omniscient narrator. I’m more interested than I used to be in how critical authority can come from ambivalence and vulnerability. Exposing yourself more fully to the work you write about. Maybe being on the other side has brought that out in me.

GE: How has being a Professor of Writing at Columbia University influenced your writing?

MJ: It keeps me on the lookout for new work and sends me back to work I’d overlooked. Work to teach, work to learn from. It keeps me in touch with the everyday mechanics of being a writer, the process of figuring it out, time and time again.

GE: As a Professor of Writing, what advice do you most often give to your students?

MJ: Write much more than you’ll necessarily use. Even if you cut, the doing it will give you work a texture, a subconscious that it won’t have otherwise. There’s also a quote from Oscar Wilde that I love: “What is first in feeling comes last in form.”

GE: What’s next for you?

MJ: I don’t know yet. I’m on leave this spring, so I’m going into the dream space one needs to find that out!

**

Margo Jefferson is a Pulitzer Prize winning cultural critic and the author of On Michael Jackson, and Negroland, the latter chosen as one of 2015’s best books by The Washington Post, the daily New York Times and Time Magazine. Her essays have appeared in many journals and anthologies, including: The New York Times Book Review, New York Magazine, The Washington Post, O, The Oprah Magazine, Grand Street, The Believer and Guernica; The Best American Essays of 2015; The Inevitable: Contemporary Writers Confront Death; Best African-American Essays, 2010, The Mrs. Dalloway Reader and The Jazz Cadence of American Culture. She has also written and performed in two theater pieces. She lives in New York and teaches in the Writing Program at Columbia University.