Interview: Andrew Mozina

Midwestern Gothic staffer Rachel Hurwitz talked with author Andrew Mozina about his book Contrary Motion, politeness, the path to becoming an author, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Rachel Hurwitz talked with author Andrew Mozina about his book Contrary Motion, politeness, the path to becoming an author, and more.

**

Rachel Hurwitz: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Andrew Mozina: I grew up in a suburb of Milwaukee, went to college at Northwestern, bounced around Chicago, earned a graduate degree in St. Louis, and have lived in Kalamazoo, MI, for the past sixteen years. Except for about four years in Boston, I’ve lived in a Midwestern city my whole life.

RH: How did growing up outside of Milwaukee influence your writing? Has living in Kalamazoo since then changed your view of the Midwest and how you integrate it in your writing?

AM: Two traits that I associate with Midwesterners—politeness and irreverence—have really influenced my writing. I see politeness and irreverence as two sides of the same coin: the more constrained by politeness you feel, the sharper your irreverence might be. It’s no accident that The Onion started in Madison, WI, and Second City grew up in Chicago. I’ve honored these traits by being an earnest smartass: most of the humor in my writing turns into pathos, and most of my pathos is for situations that also strike me as darkly funny. I love a deadpan tone that can tilt either way. Also, I experienced a lot of blowing and drifting snow in Milwaukee, and that’ll certainly harden your sensibility. In fact, even though my new novel is entirely set in the spring, the whole mood of Contrary Motion is of a man in flip flops and shorts standing in a field during a blizzard.

Kalamazoo has reminded me that there are many “Midwests” out there—from the big city midwesternness of Chicago to the midwesternness of places like Kalamazoo and the rural areas around it. As far as the effects of living in Kalamazoo go, well, sticking with the weather, the snow is generally wetter—we’re right on the edge of the lake effect—and less likely to blow and drift. It’s also much cloudier in Kalamazoo, which makes its atmosphere bleaker and suits a small city where a lot of people are hanging on by their economic fingertips. Despite all of its awesome elements, Kalamazoo is an obscure place and a good setting for people running aground or off the rails. I think my second book of stories, Quality Snacks, has a sort of forlorn, rustbelt mood that has some aspects of Kalamazoo in it.

RH: It seems like you have an interesting path into your writing career as you attended Law School for a year before receiving a Master’s in Creative Writing and Doctorate in English Literature. Can you talk about that experience?

AM: I was an econ major and didn’t think seriously about writing fiction until my senior year of college, when I was already admitted to law school. The transition from law student to writing student was fairly traumatic. I was going from a stable career that I was pretty sure I could do to an unstable pursuit that I was wildly uncertain about whether I could succeed at. I ended up getting a Ph.D. in literature in part to fill in my background—I was woefully under-read (and have never really caught up).

RH: How did this lead you to a career as a professor at Kalamazoo College?

AM: Once I got my writing and lit degrees, I looked for a teaching job. Though it sounds cheesy, I really loved the curriculum at Kalamazoo—the senior project, the study abroad program, the emphasis on internships. I like teaching, though it doesn’t leave as much time for writing as I’d hoped when I went into it.

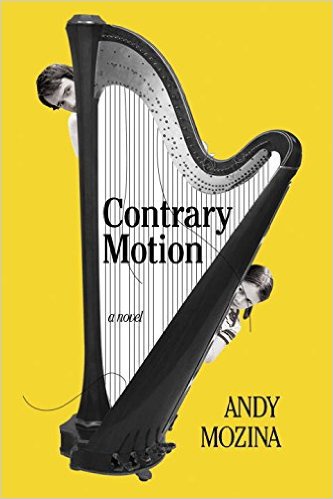

RH: Your newest novel, Contrary Motion, follows a concert harpist who is working towards an impending audition, while everything in his life explodes around him. Why did you decide to have music be such a critical part of the novel and why does Matthew, the protagonist, play the harp of all instruments?

AM: Like most things to do with writing, it was part serendipity and part intentional. My wife plays the harp, so I was familiar with that world. I’m also interested in the problem of performance anxiety, especially the idea that an extreme drive to do well can be self-defeating. A public performance is inherently dramatic, and music is one of the few art forms that usually depends on a live performance with no do-overs or edits. Focusing on an audition really brought that out. Improv comedy is probably the most vulnerable form of performance, and I decided to work that into the novel as well.

I also wanted to explore gender and sex in the book. A very high percentage of harpists working today are either straight women, lesbian women, or gay men. There are not a lot of straight male harpists like Matt out there, especially in the US. I wanted a sense of Matt going against the grain of gender expectations, of being at odds with things in general, which would be an example of contrary motion and would also accent his issues with sex.

RH: Additionally, what drew you to setting the novel in Chicago?

AM: I’ve lived in Chicago and I love the city, so the details of the place were available to me and it was fun to be there imaginatively. It’s also a really good city for harpists. The principal harpists of the Chicago Symphony and the Lyric Opera are great players and draw a lot of students. There are enough freelance opportunities for a harpist like Matt to scrape by. And Chicago also happens to be a global center for harp manufacturing, with two major harp makers, Lyon & Healy and Venus Harps. I wanted Matt to experience mechanical problems with his harp and to make a visit to a harp factory.

RH: Contrary Motion is your first novel, as your previous works have been short story collections. Was it difficult to switch to a different form of writing for this novel? Did you have any tricks for working with an extended plot such as outlining or pre-working chapters?

AM: Stanley Elkin, a fantastic and under-read writer, said that novels are about chronic characters and short stories are about acute characters, and Matt is a chronic character; his issues as a person are those he’s faced his whole life, and I thought it would take a major movement of action to test whether he’d make any progress on them. I wanted to throw a lot at him—the loss of his father, romantic difficulties, his relationship with his daughter, playing harp at a hospice, and preparing for the audition. With all of the changes and challenges he’s facing, he’s really auditioning for a whole new life. I knew braiding all of that together was a novel-length story.

My guiding tricks were to use the present tense and to confine the action of the novel to roughly the two months leading up to and including the audition. Without doing an outline, I came up with some scenes that I knew I needed and started writing them in chronological order. Eventually I used a day planner for the exact months and year in which the novel takes place and filled it in with the basic events from the novel’s timeline. All that helped me manage the logistics of a long story, but the first draft still had a quiet, short-storyish ending; it took a few tries to come up with a novel-worthy ending.

RH: Similarly, are you the type of author who writes linearly (as in the story comes together chronologically from start to finish) or do you instead work in sections and rearrange the pieces afterwards? Do you recommend one or the other to your students, or do you think it strictly comes down to personal preference?

AM: I knew I was writing toward the audition as the last major action of the book, but the first draft was basically linear. I write recursively, “from the top,” over and over, which means I read over and polish what I’ve already written dozens of times, sometimes hundreds of times, before I extend the story with a new scene. I need to feel what’s already there is reasonably OK before I move on. Once I had a complete draft, the major revisions I did were less linear. I did a lot of adding and cutting throughout the book and some shuffling of incidents.

I’m wary of making process suggestions to students unless the student has gotten stuck. Every writer has their own way, I think. Eventually, you have to make decisions about how things are going to be. If a student is putting off major decisions for too long, I intervene.

RH: What’s next for you?

AM: I’m drafting stories that are about various pariah figures—individuals or classes of people the general public judges to be emblematically bad. I’m hoping that one of those stories in particular will turn out to be a novel.

**

Andy Mozina is the author of the debut novel Contrary Motion (Random House/Spiegel & Grau). His first story collection, The Women Were Leaving the Men, won the Great Lakes Colleges Association New Writers Award. His second collection, Quality Snacks, was a finalist for the Flannery O’Connor Prize and other awards. Mozina’s fiction has appeared in Tin House, The Southern Review, The Missouri Review, and elsewhere. He is a professor of English at Kalamazoo College and lives in Kalamazoo with his wife, Lorri, and his daughter, Madeleine.