Interview: Diane Seuss

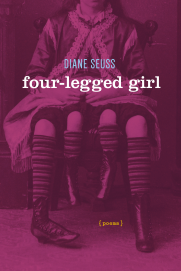

Midwestern Gothic staffer Rachel Hurwitz talked with poet Diane Seuss about her poetry collection Four-Legged Girl, the poems inside of us, lushness, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Rachel Hurwitz talked with poet Diane Seuss about her poetry collection Four-Legged Girl, the poems inside of us, lushness, and more.

**

Rachel Hurwitz: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Diane Seuss: I was raised in small towns along the Michigan-Indiana border: Three Oaks, Edwardsburg, and Niles. I left for years at a time, but when I lived in other regions I always felt like I had vertigo of the imagination. When I lived in New York City, for instance, I could never find the horizon line, and for that reason I felt unreal to myself. As you know, writers tend to have their region, the source of their myths and metaphors. For me, it’s land that many would consider un-beautiful, but many would consider me un-beautiful as well. A writer ought to write from the land where their people’s bones are buried, if they can find them.

RH: You have been on faculty at Kalamazoo College since 1988 and the MacLean Distinguished Visiting Professor in the English department at Colorado College, so educating upcoming poets is clearly a huge part of your life. What inspired you to begin teaching at the collegiate level?

DS: I never really had a life plan. I didn’t live with a focused degree of intention until recently. Both of my parents became teachers in circuitous ways. My father, after serving in the Navy during World War II, got his GED and then a teaching certificate. My mom went to college for the first time after he died young of a rare illness, probably linked to his time on the ship, and she then became an English teacher. It was a profession she knew from watching him and his colleagues, and as she has said, she wasn’t much of a waitress. I grew up listening to my mom typing her college papers about Joyce and Woolf on her old manual typewriter, and then talked with her about her lesson plans and the books her students were reading once she began teaching. I guess teaching is in my blood, given all that. I apprenticed to my parents, my mentors, as my barber grandfather apprenticed at his dad’s side. My graduate degree is in social work, and I worked in domestic assault, community mental health, and private practice for several years before I was asked to teach a course at Kalamazoo College as an adjunct. I’d been writing poems all along, and had started to publish. I’d taught writing workshops for women in the community, alongside my clinical work, for years. My teaching went well at K, and I was asked back again and again. I had ideas about what a creative writing program could look like, how it might be shaped, and after a while there was a program that relied on my presence. I found myself doing social work, teaching creative writing, building a writing career, and raising a young child all at the same time. Something had to give. Ultimately, teaching won (and my marriage lost). I am passionate about the process of students claiming their imaginations and learning how to climb inside a poem. They’ve kept me young and aged me, both at the same time.

RH: What is the most important revelation you have acquired about writing, or life in general, from your students?

DS: I guess I’d say that I’ve witnessed the fact that we all have poems inside of us, and that the work to release them is tough. All of my students have had the capacity to attune their ears to the music of language and to uncage their imaginations. Learning to listen and to self-witness is valuable in and of itself, no matter what the student ends up doing after college. I continue to be surprised by the students’ resilience and by their capacity to create, and also by how “difficult it is to get the news from poems,” as Williams writes, but how much they continue to need that news.

RH: Is there any particular kernel of wisdom or bit of knowledge that you typically give to your students or others who are just starting their literary careers?

DS: Persist. There are so many talented writers out there (thank God) and often the difference between establishing a literary career and not is dogged persistence and self-discipline, which sounds like a drag but is actually the only form of spiritual practice that ever held water for me. In terms of writing itself, never stop revising your position in relation to language. I’ve used the metaphor of a bead on a string, endlessly gliding between the two ends. Narrative and song, image and diction, wholeness and fragmentation, personality and rhetoric—never get comfortable. Never stop second-guessing whatever you do that is habitual.

RH: Many of your poems have a strong sense of place—a time, a space, even a feeling of location—even if the name of that place is never explicitly stated. How did this arise in your poetry?

DS: The place I grew up, in the rural Midwest, and when I grew up, in the 1960s, shaped how I see and experience the where. As you can imagine, without internet, social media, cell phones, Netflix, with perhaps two TV stations on a good day, and one TV show geared toward children, media was not, for me, a location. There was also no pressure to perform, no awareness that there was something beyond the present tense to aspire to. We lived for a time next to the village cemetery, which became my playground, even the platform for the theater of my imagination. A milkweed pod was a puppet. A horse on the other side of the fence was a god. I was very lucky, in that parents didn’t fear children being assaulted or murdered, and I wasn’t assaulted or murdered. I came to know myself within that setting; I only understood myself as real within a non-virtual landscape. Even when I eventually lived in a vast urban space I was sensitized to the external details that hold us up, whether we see them or not. I see them.

RH: Your latest collection of poems, Four-Legged Girl, has been called “lush as in overgrown, as in erotic, as in drunk. Lush as in botanical, both in content and florid execution” by the literary journal ZYZZYVA. Do you think this is an adequate representation of your work?

DS: I love that review, and I think Maggie Millner, its author, is a brilliant writer. She was right on in her description of what I hoped for in Four-Legged Girl. The longest poem in the collection is called “I can’t listen to music, especially ‘Lush Life,’” and that jazz standard, written in the mid 1930s by Billy Strayhorn, really sets the tone for much of the book. Lushness, in the song, is erotic and swoony, yes, and also refers to the use of the word as a noun for someone who is over-the-edge, a drinker, a person lost to nightlife and shadows. I loved that double-usage, and I think it frames the book’s narrative line and emotional landscape. Its speaker contemplates her life as a lush lush. Hopefully, by the end, she comes to a kind of present-tense lushness that is synonymous with poetry.

RH: Similarly, your poems seem to range in tone from light and comical to intense and dark. Where do these stark contrasts come from in your inspiration and tone? Do you prefer writing one to the other?

DS: For me, the two are all tangled up in each other—the comic and the dark—like a squash vine and a patch of deadly nightshade. It’s one distinction, I think, of writing from the Midwest. Yes, dark humor is a literary tradition in many regions inside and outside of the U.S., but the Midwest has a particular brand that I’m not sure how to put into words. It’s linked to the Southern Gothic but it has its own flavor, like my southern friends have different recipes for their funeral salads than we do up here. Many in Michigan are from families that migrated up here from the south. We almost remember that particular brand of jackassery, but we’ve lost even the distinction of being southern jackasses. Meteorologists, even if our weather is dramatic, rarely mention the Midwest. We’re a poltergeist region, trapped between areas with actual identities. Mid-career, midlife, middle of the road. That entrapment, that near-invisibility, is part of our tradition of dark comedy and one of its tropes. Also, if a Midwesterner gets too intense they get razzed. And if they get too funny they’re seen as trying to rise above the ranks. That’s a long answer to a good question, and I’m not sure I’ve answered it. (P.S. My mom makes a funeral salad called “Green Gag.”)

RH: Your poems seem to vary greatly in style and form—some are long and structured with clear stanzas, while others, such as “Song in my Heart,” are much shorter and freeform. Do you plan the form prior to writing your poems or is that a natural part of the process? Do you implement your structure in editing or is it present from the get-go?

DS: The skeletons of my poems usually, though not always, emerge as I’m writing the poem, but revision for me is about fiddling with structure. As you can tell, I’m not as much into the architecture of my poems as many contemporary poets are. I see structure as the bones that deliver the flesh, which could be considered a weakness, in both poetry and embodiment.

RH: Who do you consider to be the greatest influence on yourself and your work—either literary or personally?

DS: May I have two? The first is my mentor, Conrad Hilberry, who found me after reading one of my poems when he judged a little contest that I’d entered without realizing it was only for adults. My entry was typed single-spaced, with no awareness of a left margin, on a piece of paper I tore out of a notebook. He came to Niles to do a poet-in-the-schools gig at the high school in town and sought me out at my high school outside of town, which was basically in the middle of a cow pasture. From there, he sent me books, got me help to go to college, including one by Diane Wakoski, called Inside the Blood Factory. He never told me to simmer down or hold my horses. Second, my mom, her voice, her hilarity, her endurance, her solitude, her lack of vanity, her independence, and her funeral salad.

RH: What’s next for you?

DS: My next book of poems, Still Life with Two Dead Peacocks and a Girl, will be out in 2018 from Graywolf Press. It concerns art with a capital A, specifically, early still life painting, and the connection between still life, which occupied the lowest rung on the art historical ladder, and the rural Midwest, and traditional women’s work, both in the house and on the canvas. It sounds stuffy but it isn’t. Writing that manuscript was the most powerful experience of my life. It pretty much roiled off of me, out of me, like water breaking or gas pouring out of a broken pump. I’m currently in revision mode for that book, and beginning to work on something new that will resemble a memoir, tentatively titled Auto-Body.

**

Diane Seuss’s most recent collection, Four-Legged Girl, was published in 2015 by Graywolf Press. Her second book, Wolf Lake, White Gown Blown Open, won the Juniper Prize and was published by the University of Massachusetts Press in 2010. Her fourth collection, Still Life with Two Dead Peacocks and a Girl, is forthcoming from Graywolf Press in 2018. She has published widely in literary magazines including Poetry, The Iowa Review, New England Review and The New Yorker. Seuss is Writer in Residence at Kalamazoo College.