Interview: Travis Mulhauser

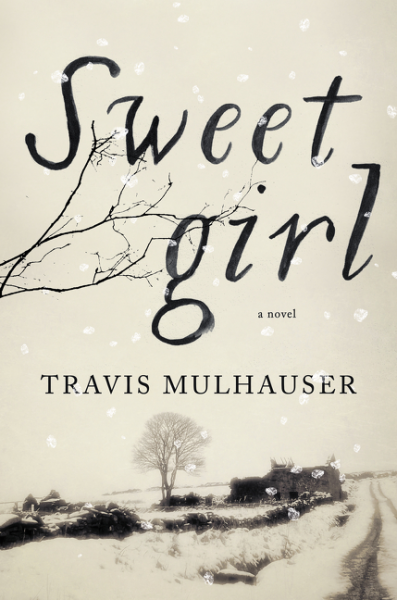

Midwestern Gothic staffer Giuliana Eggleston talked with writer Travis Mulhauser about his novel Sweetgirl, humanity in easily-villainized characters, the redemption to be found in humor and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Giuliana Eggleston talked with writer Travis Mulhauser about his novel Sweetgirl, humanity in easily-villainized characters, the redemption to be found in humor and more.

**

Giuliana Eggleston: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Travis Multiuser: I’m from Petoskey, Michigan and lived in northern Michigan through my early twenties. My grandparents from both sides lived in the Detroit area, and much of my family is still found in the Mitten. I will always claim Michigan as my home, so far have stuck to northern Michigan in my fiction writing, and maintain relationships with friends from Michigan I’ve had my entire life. And if we’re being completely honest, my fandom for the Detroit Lions and Michigan State Spartans very much keeps me connected to the state and identifying as a Michigander. My kids, to this point, have maintained those rooting allegiances and it still strikes me as odd that they are actually from North Carolina and not Michigan.

GE: How does the setting of a small northern Michigan town, specifically in the winter, play a role in your new novel Sweetgirl? Why did you choose to set the story in that place?

TM: I write about northern Michigan because it’s the place I know the best, even though I’ve been in the south for some fifteen years. I think the landscape will always be interesting to me, in part because it’s beautiful and severe, and in part because its where I spent my formative years. They were also pre-Internet years and when I think of my childhood I feel like I spent an inordinate amount of time staring out of windows — in the backseat of my parent’s car, in school, at home — I just have that landscape stamped in my consciousness in a way that I don’t for other places I’ve lived and visited.

My mom used to go for drives. She’d take me, my brother and sister on these aimless cruises around town and all the “country roads.” We’d listen to her 8 tracks, I particularly remember Kenny Rogers’ “The Gambler” and a whole shitload of Neil Diamond and I’d just listen to the music and stare out and let my mind wander. It might not sound like it — I know people have strong feelings on both sides of the Neil Diamond debate — but it was actually pretty wonderful.

GE: Going along with the small town setting is an atmosphere of drug use. Do you see the drug culture, specifically meth, as being an unavoidable part of the landscape?

TM: Yes, for these characters. But like anywhere I feel like drugs can be found if you want to find them, and in most places, for most people, avoided if you’d prefer to stay away. I think Shelton is the type of guy that would always be able to locate a buzz — if he was stranded on a desert island it would probably take him less than a week to figure out how to extract some sort of syrup from an indigenous mineral, mix it into a powder and smoke it through a bamboo shoot to get blasted. Shelton will be a handful wherever he is and I think the small-town stuff — he rides snowmobiles instead of the subway — is secondary to that core element of his character.

GE: How did you go about creating the relationship between Percy, the main character, and her mother Carletta, a meth addict? Was it difficult to write about a meth addict mother and a child that cares nonetheless?

TM: It wasn’t difficult at all. In fact, of everything in the novel, I might have been most comfortable writing about Percy and her complicated feelings about her mother and her mother’s addiction. I have never thought of addiction or drug use as a moral failure. Ok, maybe I did when I was seven years old and the War on Drugs was being launched — a catastrophically stupid war, even by war’s standards — but the thing about “the enemy” in that war is that at every level it is our friends and family members, our actual selves, that we are fighting. I’m not saying anything new here, but it’s what makes addiction so God-awful and such fertile ground for stories — it’s complex and rife with peril and it happens in our living rooms and in our hearts.

GE: Some of the characters in Sweetgirl could have been easily villainized for their dependency on drugs and violent actions, yet you seem to be able to bring a sense of humanity to each that the reader can relate to. What was your process like in creating these characters with such a wide – and human – range of characteristics?

TM: My wife is a death penalty attorney — she represents people on death row and tries to keep them from being executed — and watching her do that work has taught me a ton about the incredibly wide spectrum of actions people are capable of. People who commit violent crimes should go to jail for those crimes, but there is, in almost all cases, a lot more to those people than the worst things they’ve done. I think that’s where I’m coming from with Shelton and Carletta.

GE: Sweetgirl is at times so incredibly heartbreaking that it seems impossible anything in the story could be funny, yet humor is also a large part of the novel. How do you go about finding humor in the situations that seem most bleak?

TM: The funniest book I’ve ever read is Wolf Whistle by Lewis Nordan, which is a fictionalized account of the murder of Emmett Till. The tragedy is profound and deeply felt in that book, and while there is not a single note of false hope, there is redemption in the humor — which is explosive and seems directly correspondent to the depth of despair. I don’t know why that is, or exactly how it works, but I think the funniest stuff often comes from the most painful. I think laughter, real laughter, is a healing agent and probably the most powerful one for me, personally.

GE: When and why did you decide to write this novel? Did it form all at once or did the idea take a while to grow?

TM: It started with the image of a young girl discovering an abandoned baby. The girl was wearing a hooded sweatshirt and I had the sense that she was in as much danger as the baby. I don’t know where the image came from or why I sort of became possessed by it, but that was what I followed — that image and the sense I had that the baby and the young girl would be able, somehow, to help each other.

GE: How do you know when a piece is finished?

TM: Great question. There are two answers: 1) I don’t. 2) Gut feeling.

Both of these things are simultaneously true, I think. Deep down I think I usually know if something is done, and by done I mean it’s ready to be handed off to a reader. Maybe my wife, or a writer friend, maybe my agent or editor. Done in the sense that I’m done with it for now. I think on some level I know when I have reached that place, but it can be obscured pretty easily by fear, or by impatience.

The fear says: You’re not done! (I actually am done, but am afraid it sucks)

The impatience says: You’re done! (I actually am not done, but really wish I was)

Impatience has caused me to rush manuscripts and fear has made me sit on them for too long. I wish there was an easier litmus test. An actual litmus test would be ideal — dip the manuscript in the solution and if it turns blue it’s done, red if it’s not. A digital litmus test would obviously be preferable, but I’d be happy to start with something in a lab. Old school.

GE: What’s next for you?

TM: Working on my next novel, also set in Cutler County. And I’m almost to the point where I can start talking about it in specifics! (Fear and impatience aside…)

**

Travis Mulhauser is from Petoskey, Michigan. He is the author of two works of fiction, most recently the novel Sweetgirl from Ecco/Harper Collins. He lives in Durham, North Carolina with his wife and two children.