Interview: Dan Raeburn

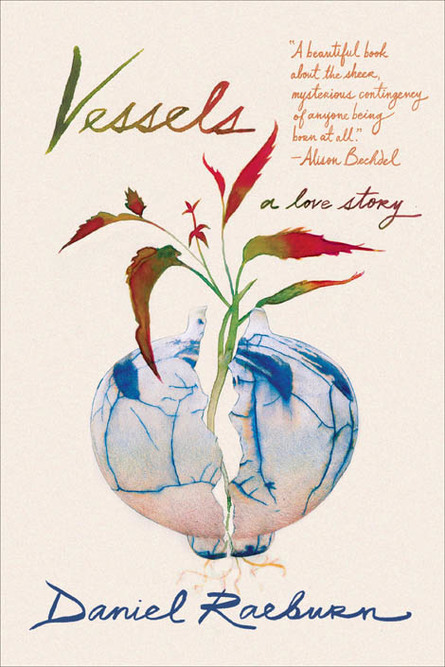

Midwestern Gothic staffer Sydney Cohen talked with author Daniel Raeburn about his book Vessels, looking for a home, birth and death and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Sydney Cohen talked with author Daniel Raeburn about his book Vessels, looking for a home, birth and death and more.

**

Sydney Cohen: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Daniel Raeburn: I lived in Iowa City for most of elementary school and college. After college I moved to Chicago, where I’ve been for the past 23 years. I think my deepest connection has to be the sound of insects at night. Crickets, cicadas, who knows what whirring and whining so loudly that the summer nights sound electronic. It’s a jungle out there, and every time I hear it I feel like I’m ten years old again, sweating in bed in the dark with the windows open.

SC: Your new book, Vessels, deals with the universal themes of love, loss, and sacrifice in regards to your personal history with building a family. Though these themes can be found in stories all over the globe, how did the Midwest, and its influence, play a role in your experience with them?

DR: The book’s about looking for a home, in part because I felt like I’d never really had one. I start the story when I’m 33 years old; by that point I’ve already moved 24 times in my life. So I’m ready to settle down, to make a home in Chicago. Having kids becomes a part of that, but not in the way I’d imagined. When Bekah’s and my firstborn died it was like an atom bomb exploded, and our apartment in Chicago became ground zero. Instead of trying to move on, to get away to somewhere new, we stayed in that place. We toughed it out. We had more kids there, and at least one more miscarriage. Those births and deaths were a big part of what made our apartment and the city itself our home. To me they’re haunted, but not necessarily in a bad way.

SC: Through your writing of Vessels as a memoir, what was your process of translating your own real life events to literature and prose? Did you write as you experienced things in the moment, or write in reflection of those events?

DR: Both. I wrote most of Chapter Two, which is about the stillbirth, in the nine months that followed it. I published that as a stand-alone story and thought I’d moved beyond it. But I found myself keeping a more or less daily journal for years afterward, just to write down my many thoughts about fatherhood: about Irene, our child who died, and about Willa and Hazel, who were alive and well. I thought that this was a distraction or relief from the book I was really working on, a book about comic books. But eventually I realized that those journals were the book I really cared about. So I went back and distilled them from the original 600 pages or so down to the novella-length memoir. The hardest part, other than cutting, was weaving in the preexisting published piece, making it fit into this much larger and longer story.

SC: Your book deals heavily with literal birth and death, telling the story of your and your wife’s struggle with multiple miscarriages as well as two healthy births. Beyond the literal, how does your book approach and discuss figurative birth and death? How did you weave together the literal and the figurative?

DR: This goes back to what I said about Irene’s birthday being ground zero. If my life’s a number line, she’s the zero on it; her death erased everything that had happened to us before. In that sense it was a kind of death for me too; but also a kind of rebirth in that I had to basically start my life over again. I didn’t really realize this until the day, many years later, when I was writing about her and abbreviated her name for the first time: Instead of “the day Irene died,” I wrote “the day I. died.” That’s when it clicked.

SC: Vessels also explores the progression of your relationship with your wife, from your first meeting throughout your building of a family. How did your perspective on your marriage and its dynamic change through the process of writing about it?

DR: When a child dies, it’s almost like something else has to die too. Usually it’s the marriage that produced the child. That was definitely the question in our marriage. Ultimately I realized that I had to end the book on an ambiguous note; to end by making the point that the same thing that broke our marriage had also cemented it.

SC: The Imp, a series of essays spotlighting various underground cartoonists, is your most previous work, published in the late 90s/ early 2000s. In terms of your writing, where were you mentally in the interim between The Imp and Vessels, published in March 2016? Why so long a break between your published works?

DR: Part of the reason is kids. I’ve been extremely busy for the past ten years raising two small children, who give you no rest whatsoever. Another reason is the process I described in the book. I was under contract to write a big book about comics, and after Irene died, my desire to write that book died too. But I didn’t realize it for several years. Once I did I paid back the advance to my publisher and wrote this book instead. Which took forever, in part because the book itself could’ve gone on forever. Every day was a new piece of material, a new development, a new wrinkle. I like to say that it took me a long time to make the book short.

SC: How did the experience of writing about other people, as in The Imp, differ from writing about yourself? Which do you prefer?

DR: No preference. They’re equally difficult, and the truth is that all my writing about cartoonists said as much about me as about the subjects themselves. The true subject of an essay is usually the essayist himself, and my essays about cartoonists were no exception. And the memoir’s not only about me; even though my consciousness is the main character, so to speak, so is my wife, and she’s the hero of the story. Memoirists worry more about their portrait of other people than their portrait of themselves.

SC: What’s important to keep in mind when writing a memoir?

DR: That it’s not about you. It’s about your reader, about her experience as a reader, not necessarily yours as a writer, or even as a character. You have to keep the reader in mind constantly. Most novelists and poets have this problem too. We all do; that’s one of the things that makes writing so difficult.

SC: What’s next for you?

DR: I’m not sure. Teaching full time and reading as many books as I can, that’s for sure. I’d like to go back to writing something that’s journalistic or essayistic, and I’m playing with a few ideas, including a true crime piece. But it’s way too early in the process to say.

**

Daniel Raeburn is the author of Chris Ware, a book of art criticism, and Vessels, a memoir. His essays have also appeared in The New Yorker, The Baffler, Tin House, and in The Imp, his series of booklets about underground cartoonists. He’s been awarded fellowships from the McDowell Colony, the Vermont Studio Center, the Howard Foundation, and the National Endowment for the Arts. He and his wife and daughters live in Chicago, where he teaches nonfiction writing at the University of Chicago.