Interview: Philip Metres

Midwestern Gothic staffer Megan Valley talked with poet Philip Metres about Sand Opera, creating a space for voices, a list of invaluable advice for writers, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Megan Valley talked with poet Philip Metres about Sand Opera, creating a space for voices, a list of invaluable advice for writers, and more.

**

Megan Valley: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Philip Metres: I grew up in the leafy northern suburbs of Chicago, but I didn’t feel Midwestern until I went off to college on the East Coast and felt distinctly out of place. I remember hearing Uncle Tupelo’s No Depression on our college radio station, and it felt like home. I think of avant-garde poet Dmitry Prigov’s poem:

I’d be Catullus in Japan

And in Rome, Hokusai

And in Russia, I’m the same guy

Who would have been

Catullus in Japan

And in Rome, Hokusai.

I suppose I’ve always felt a little out of place.

A few years later, I spent six years in Bloomington, Indiana, pursuing my Ph.D. and M.F.A. The past fifteen years I’ve been teaching in Cleveland, Ohio. Three different MidWests—some partly gothic; occasionally, when I drive by the abandoned houses in certain neighborhoods of postindustrial Cleveland, I feel in the presence of ghosts. The killers were dressed in suits and wielded redlines, racially-selective loans, and variable interest rate mortgages.

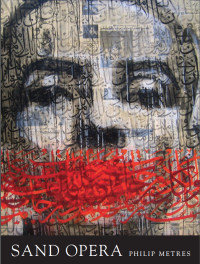

MV: Your most recent poetry collection, Sand Opera, received Honorable Mention for the 2016 Arab American Book Award. What part of the book are you most proud of?

PM: It’s a difficult question to answer, because I’m grateful that the book exists, that the poems came to me and wrestled me into existence. The book wrote me as much as I wrote the book. I’m grateful, too, that a good number people have read and reviewed it, and that my friend John Morris is now in the final stages of editing a Teacher’s Resource Book for Sand Opera, which will enable high school and college teachers to keep teaching the book, even though that war is more or less over (though the wars are never over). I wanted to create a space for the Iraqi (and American) voices that weren’t being heard in the mass media narrative of the war. I hope I honored them, my Iraqi friends, and those whose words I read through testimonies of the war.

MV: What do you wish you had known before you began writing?

PM: I’ve written a half-dozen clichés and erased them in trying to answer this question. The advice I tend to give to my students about writing poetry is this:

1. Mightier than the sword is the pen. Carry it always, and something to write on.

2. Explore the possible. Read and steal greedily from “the mind of the past” (Emerson).

3. Get in the mood: find solitude and quiet the mind. The world inspires us, but also distracts us. It is both source and obstacle. Love it the way you love any dangerous friend.

4. Imagine (or hear) a particular voice in a situation and let the voice speak through you. Steven Wright: “I am the receptionist of my brain.” Listen to contrariness.

5. Handwrite without erasing OR don’t use the delete key: go forward. Flow downstream. (This is for the first draft only!)

6. Move through image, not idea. “Show, don’t tell.”

7. Listen to the sounds of words; let the music move, but don’t be bound by rhyme.

8. Experiment with form: lineation and stanzas should enhance the meaning.

9. Flip the script. Surprise yourself. Discover where you are going and let the ending find itself. Explore “the turn”— where the poem surprises by reversing flow.

10. Put it away at least overnight; let the inspiration cool off. What is durable will remain mysterious.

11. Show it to others without explanation and listen (really listen!) to their feedback.

12. Revision is where you show your courage and you let go your ego. Revise toward where the poem is going, not what you wanted it to be.

MV: Sand Opera is built off of the position of Arab Americans being “named but unheard.” How can poetry confront that problem?

PM: Trump (whom I hope will be a mere blip in our national story) has emboldened those who see Americanness through a lens of imperial whiteness. People of color, undocumented workers, and women have been derided or endangered by the rise of this reactionary fervor. So much of what’s happening is demonizing. Writing poetry can be a site of listening to one’s own voice as it emerges on the page, surprising its writer with its otherness and self-ness all at once—just as reading poetry can be, as we explore the mystery of what it means to be human. Poetry is one of many art-technologies involved in this process, but it’s the one that’s chosen me.

MV: You also translate Russian poetry. What aspects of Russian poetry have been the most influential on your own?

PM: I went to Russia after college on a fellowship to study “Contemporary Russian Poetry and Its Relationship to Historical Change,” partly because I wanted to learn about Russia (the so-called “Evil Empire”) and its legendary poets, but partly because I wanted to learn how to be a poet myself.

Translating and meeting those poets completely transformed my idea of poetry and its relationship to the political sphere—I became less interested in poetry as a political weapon and more interested in its alternate way of being, both part of but also beyond politics, or rather, beneath all politics. The primal ground of being. Translating poets like Sergey Gandlevsky and Lev Rubinstein and Arseny Tarkovsky became an education in poetry’s possibilities. I know the poets I’ve translated better than any other poets because I’ve lived inside those sonic language architectures longer than in any other poem.

MV: You’ve said in a past interview that American culture is “addicted to the war story.” How does Sand Opera approach and treat that “addiction?”

PM: Our culture seems almost starving to hear soldiers’ voices. On the one hand, I understand it; the soldier is one who has faced death directly, and lived to tell about it, in the service of country. On the other hand, I find it ominous and even dangerous how these voices colonize our discourse about what war (and what other countries and people) look like. Nearly always, in the traditional war story, the countries and peoples end up as stage props in the story of a soldier coming of age. War should not be a rite of passage for our youth; it should be a last resort when our very existence is at stake. The Iraq War was not merely a tragedy; it was a criminal imperial decision that led to further criminality, mass death, and, ultimately, ISIS. My approach in Sand Opera was to listen to Iraqi voices, and all those whom that war affected, as well as to explore the operating procedures of the larger War on Terror: extraordinary rendition, torture, Guantanamo Prison, etc.

MV: What would you be doing if you weren’t a writer?

PM: I’m already living many lives at once, as we all do: husband, father, son, teacher, church-goer, musician, basketball coach, etc., etc. Other possible vocations? Diplomat and therapist and journalist all come to mind. I’m interested in peace-building and peacemaking, with ourselves and with others.

MV: You’ve said Sand Opera had been in the works for about a decade before it was published. How did the collection change in that time, especially as much of the poetry addresses political situations that were ongoing during that time?

PM: It moved from being a book attempting to intervene on an ongoing conflict to one that needed to last for the ages. Dealing with that fact only made the book better. Only time will tell if it has been successful. Perhaps it is the humus from which other better poems will emerge. I’m grateful, for example, that Solmaz Sharif found the arias helpful in the process of writing her first book LOOK, which was a finalist for the National Book Award.

MV: What’s next for you?

PM: I’m working on a handful of projects, which alternate depending on my mood: The Flaming Hair of Fate (a memoir about living in Russia), Shrapnel Maps (poems on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict), The Sound of Listening (essays on poetry), a book of translations, and a book of interviews with Russian poets. I love getting lost in words.

**

Philip Metres is the author of Pictures at an Exhibition (2016), Sand Opera (2015), I Burned at the Feast: Selected Poems of Arseny Tarkovsky (2015), To See the Earth (2008), and others. His work has garnered a Lannan fellowship, two NEAs, the Hunt Prize for Excellence in Journalism, Arts & Letters, two Arab American Book Awards, the Cleveland Arts Prize and a PEN/Heim Translation Fund grant. He is professor of English at John Carroll University in Cleveland.