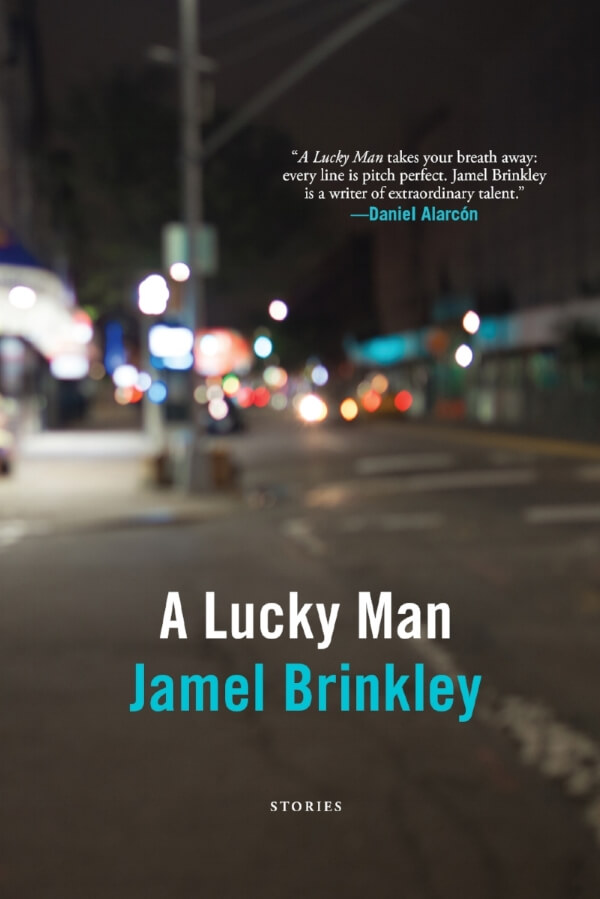

Interview: Jamel Brinkley

Photo Credit: Arash Saedinia

Midwestern Gothic staffer Kathryn Cammell talked with author Jamel Brinkley about his debut collection A Lucky Man, the challenge of writing a short story, how to overcome rejection, and more.

**

Kathryn Cammell: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Jamel Brinkley: I drafted and/or revised every story in my debut story collection while living in the Midwest—in Iowa City and Madison, specifically.

KC: Your forthcoming debut, A Lucky Man, is a collection of fiction short stories about the interwoven lives of men and the nuances of their relationships with other people in their lives. What drew you to this subject matter?

JB: I didn’t set out to write about one specific thing, but I suppose I must have been drawn to my subject matter by my own experiences, memories, and obsessions. In my life as a boy and then a man, I’ve thought a lot about masculinity (especially black masculinity) and human relationships of various kinds. A Lucky Man is a work of the imagination, but really I wrote about the kinds of people I’ve known, whose lives are rich, complicated, nuanced, and full of love and loss.

KC: What is the importance of short stories, especially when many short story authors are pressured to write longer works?

JB: I’m tempted to say that simply resisting the market-driven preference for longer works itself makes writing and reading short stories a virtue. But I won’t stop at that. The compression required in a short story, whether it’s five pages or thirty pages, presents a distinct formal challenge (for the writer) and pleasure (for the reader) that you don’t get from a longer work, which has its own challenges and pleasures. Whereas even good or great longer works typically have the freedom to slack off every once in a while, good short stories usually have to work from sentence to sentence, in a lapidary way. Also, and maybe more importantly, I think they tend to mirror how I, and maybe other people, actually narrate life, not as one long cohesive, plotted narrative, but as a collection of smaller stories, each one told as though at a bar with a friend: “Hey, let me tell you what happened the other day…” I like that stories tilt in some ways toward poetry, and I like the feeling that you can hold an entire story in your mind.

KC: The stories in your collection focus on luck and its absence, in the lives of men living in Brooklyn and the South Bronx: how did your own childhood growing up in those places influence what you chose to explore in your stories?

JB: As I mentioned, I don’t feel like I consciously chose to explore any particular thing in my stories. My childhood growing up in a particular place probably influenced me the way anyone’s childhood growing up in a particular place would. Toni Morrison said that “universal” is a word hopelessly stripped of meaning. She went on to say, “Faulkner wrote what I suppose could be called regional literature and had it published all over the world. It is good—and universal —because it is specifically about a particular world. That’s what I wish to do. If I tried to write a universal novel, it would be water.” I wrote about what I didn’t know about the particular things I know, and what I know is, largely, Brooklyn and the Bronx. If I managed to depict, even in an oblique way, a fraction of what life in those places has been like, then I can be happy with that.

KC: How do the places that you lived in the Midwest compare to Brooklyn and the South Bronx? Is there anything from your time in each place that you can identify as influencing your writing?

JB: The thing that struck me immediately about Iowa City and Madison is the quiet in those places, relative to where I lived in New York. Sure, there was the occasional band of frat boys hooting and hollering, or the sound of a car passing in the rain, but mostly my sense was, “Wow, it’s really quiet here.” I don’t know that this quiet influenced my prose itself, although maybe it did. Some stories, many of the ones I began in the Midwest, do have a quieter prose style than the stories I arrived with. Mostly, I think the quiet and relative lack of distractions just helped me get more writing done.

KC: Since having recently gone through the process, do you have advice for writers who are looking to get their books published?

JB: Try not to get too bent out of shape about rejection. My book was rejected by the vast majority of publishers who looked at it. If possible, try to choose an agent and an editor whom you instinctively trust, who push or nudge you as necessary but always show respect for you and your work and understand what you’re trying to do. Have people in your life who are also going through the same process you are, or who have gone through it. They will understand the very particular challenges and anxieties involved in the process. Regardless of what is happening, good or bad, keeping writing and reading so you stay connected to the fundamental joys that made you want to be a writer in the first place.

KC: What does your writing process look like? Do you have a specific environment where you find you work best?

JB: I always work at home, wherever home is, unless I’m at a residency or something like that. I’m not a writer who can work in, say, a cafe. I think my process is primarily character- and language-focused. I write first drafts slowly, asking lots of questions, nitpicking my way from sentence to sentence, but I try not to think too much about issues of craft or the kinds of things that usually come up in workshops. If I’m not under pressure from a deadline, when I’m done with a draft I let it sit for a while. When I look at it again, I start thinking more deliberately about craft: scene, point of view, dialogue, etc. I find Robert Boswell’s transitional drafts method helpful. Finally, I try to make sure I haven’t “crafted” the life out of the story. If I feel stuck, then I have trusted readers I can turn to.

KC: What’s next for you?

JB: I want to write more stories, and maybe something longer too. We’ll see.

**

Jamel Brinkley was raised in the Bronx and Brooklyn, New York. He is a graduate of Columbia University and the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. His work has received fellowships from Kimbilio Fiction and the Wisconsin Institute for Creative Writing, and beginning this fall he will be a 2018-2020 Wallace Stegner Fellow in Fiction at Stanford University.