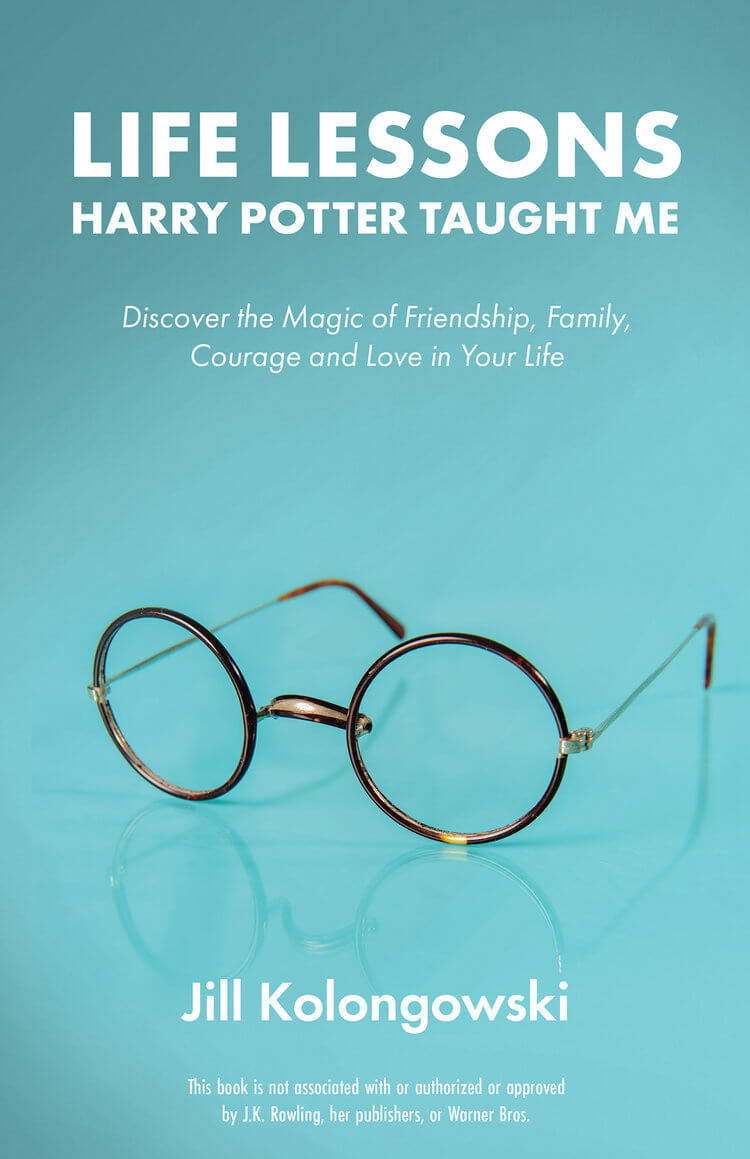

Midwestern Gothic staffer Carrie Dudewicz talked with author Jill Kolongowski about her book Life Lessons Harry Potter Taught Me, how to juggle writing, editing, and teaching, her becoming a nonfiction writer, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Carrie Dudewicz talked with author Jill Kolongowski about her book Life Lessons Harry Potter Taught Me, how to juggle writing, editing, and teaching, her becoming a nonfiction writer, and more.

**

Carrie Dudewicz: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Jill Kolongowski: I was born in a small town in Michigan, and lived there until I graduated from Michigan State University and moved to Boston for my first job. Now that I live in California, my connection to the Midwest feels even stronger—I feel like my whole identity was shaped by the long, gray winters and the summers in the lakes. It took leaving to realize that.

CD: You’re a writer, a professor at the College of San Mateo, and the managing editor at YesYes Books. How do you balance all of these roles? How do these different jobs connect to and influence each other?

JK: I don’t balance them. (Just kidding — kind of.) As far as balance, it’s not always terrific; I find I have to be very deliberate about how I spend my time. When I switch from grading papers to writing, or writing to editing — switching from one part of my identity to another — I attempt to close off the other parts of my brain. When I was writing my book, I sometimes spent 10 minutes meditating in between, or I had to move from my apartment to the library or a coffee shop, just to force my brain to switch gears and focus. It sometimes works, and sometimes doesn’t. It’s a balance I’m continually negotiating.

I grew up knowing I wanted to be a writer and editor, but insisting that I did NOT want to be a teacher. I had major stage fright and imposter syndrome. I still have stage fright and imposter syndrome, but when I received a teaching fellowship for my MFA, I fell in love with teaching. Now, I see teaching, editing, and writing as three prongs of the same impulse — loving writing, and wanting to share that with others. On some of my toughest teaching days, my students knock me over with their insight or their writing, which can shake me out of my own writing challenges and inspire me to do better. When I’m excited about a great writing day, or a breakthrough, or have read a new favorite essay, I share all of those with my students. I hope seeing me as a working, struggling writer can help them through their own struggles. And working with the innovative and boundary-pushing and blazingly insightful poets at YesYes makes me into a student, just reading and learning from them.

CD: YesYes Books is an independent press known for high-quality poetry, fiction, and art. What is the most rewarding aspect of being an editor at this press? How does it differ from other editing jobs you may have had in the past?

JK: The most rewarding aspect has to be the work I get to read (and the writers themselves!). The editors, KMA Sullivan and Stevie Edwards, somehow manage to find and amplify writers who not only make fresh and sharp and important work, but who are also wonderful, smart people to be around. I’m not a poet, but I feel like YesYes is giving me the poetry education I was too scared to seek out as an undergraduate. YesYes feels personal in a way that many other editing jobs have not.

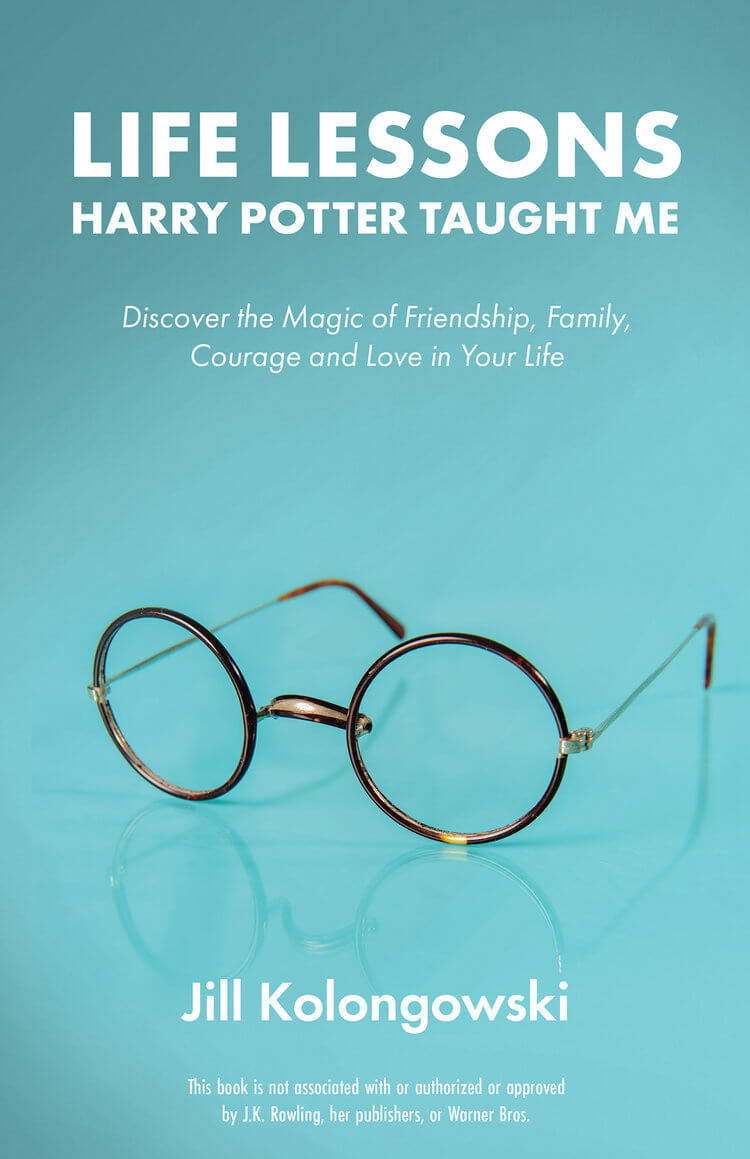

CD: Your debut book is called Life Lessons Harry Potter Taught Me. The Harry Potter series is a cultural phenomenon, one that millions of people are familiar with and devoted to. Tell us more about your experience with Harry Potter. When did you start reading the books? What made you decide to write a book about Harry Potter?

JK: I read Sorcerer’s Stone when I was 12 years old. The first two books in the series were already out by then, and my younger sister read them first and told me I HAD to read them. I was hooked. I’d always loved books about kids being extraordinary on their own (I loved The Boxcar Children and Lloyd Alexander’s The Chronicles of Prydain), and my sister and I loved to play orphan (sorry, Mom and Dad). It wasn’t about the fact that most great children’s stories begin with lost parents, but it was about the idea that children had power and agency, and could really do something with that power. I’ve loved Harry Potter my whole life —reading and rereading, standing in line for each midnight movie showing. I’m kind of unusual in that I didn’t partake much in the online Harry Potter fandom — I didn’t read fan theories, I didn’t go to book release parties. I felt weirdly competitive and private about Harry Potter. I thought that someone couldn’t possibly love it more than I did, and in a way, I wanted to keep Harry Potter all to myself. That’s been one of the really beautiful things about writing this book—I’m engaging with the Harry Potter community in a way I was too afraid to when I was younger. And I’m so glad! I regret not having done it sooner. This book and Ulysses Press are unusual too—rather than authors submitting manuscripts, the press comes up with ideas they see as missing in the market, and find writers to do it. The editor put out a call for writers on a vague “Harry Potter project” and a friend of mine saw the call, knew I loved Harry Potter (I had once sorted all 50 members of our online writing group into Harry Potter houses, with detailed explanations about why), and sent the information to me. As soon as I heard that the project was a book about lessons learned from Harry Potter, I was elated. If you read the book, you’ll see that I don’t really believe in fate or destiny, but oh did I feel like this was the book I’d been waiting my whole life to write, even if I didn’t know it. I was ready to make that private love public. And thank the Goddess Hermione, Ulysses liked my pitch enough to choose me to write it.

CD: In your book, each chapter is named after a Potter-universe spell and subtitled with the subject/”life lesson” of the essay. How did you match each spell with each life lesson? Why did you choose to structure the book in this way?

JK: When I was considering how to organize the book, spells were my very first thought. I considered a few alternate ideas — organizing around people, or around places in the Harry Potter universe (the Divination classroom, Hogsmeade, the Gryffindor common room, etc.), but the spells felt right from the very beginning. Some of the spells came really easily (like “Wingardium Leviosa” for the chapter about Hermione, or “Riddikulus” for the chapter on laughter), but others were harder to match. Should “Legilimens” (the spell used to read minds) be about empathy and kindness, or about self-examination (which is where it ended up, in the good and evil chapter)? I made a list of spells that appeared in the books and when they were used, and tried to use them as a metaphorical bridge. Other than “Wingardium Leviosa,” my favorite is probably “Lumos” as a metaphor for curiosity and wonder. For us Muggles, the real magic in the series is the thing that’s most inaccessible to us, so pairing spells with themes seemed like a way to give readers metaphorical access to that magic.

CD: People of all ages are obsessed with the Harry Potter series and, like you, could or do write about their feelings for Rowling’s creation. What do you think makes these books so widely loved?

JK: The world of Harry Potter is so beautiful — I think as kids, it allowed us to enact many of our deepest-held fantasies — being able to breathe underwater, being able to fly, riding dragons, flying on broomsticks and petting baby unicorns, but also being powerful and being trusted to do great things. But even more than the aesthetic joys of the series, I think the genius of the series is in the complexity of the characters. Harry is the hero, yes, but he’s also kind of terrible — while often being fiercely good, too. Snape is a true hero, but he’s also a coward and can be cruel. And Dumbledore is kind and forgiving and also manipulative. Hermione is a beautiful, loyal friend, but is sometimes inflexible. Ron adopts Harry like he’s family, but his jealousy and insecurity make him occasionally fickle. And which of us hasn’t been all of these things at the same time? For many of the characters, those imperfections are what make them great, when they’re humble enough to trust each other and work together. They are allowed to succeed despite their flaws, and even because of them. The series is so beloved because we get to escape into the world, and at the same time, find ourselves there.

CD: You write primarily creative nonfiction and have had many essays published in various journals. Why do you choose to write creative nonfiction rather than fiction? Where do you find your inspiration to write essays?

JK: I started off as a fiction writer because I started off as a fiction reader. My first love was fiction, and I only discovered creative nonfiction in college. I needed an elective and since I was terrified of poetry, I took creative nonfiction with Marcia Aldrich and realized that that’s what I had been writing all along. All of my short stories had been true stories with my friends’ names changed, or wish fulfillment of some kind. As much as I still love and admire fiction, I feel incapable of writing it. I never had that thing that fiction writers seem to have of walking around with characters in their heads. All I had (and have) are true stories, and the only way I seem to be able to write is to try to render those stories as vividly and truly as I can. In college I read an essay by Lisa VanAuken in Fourth Genre called “Rooster-Fish.” The entire plot of the essay revolves around her finding a cockroach in her apartment (though it becomes about fear and self-doubt instead), and that was a revelation for me — that nonfiction doesn’t have to be big or splashy in order to create meaning. For inspiration, I love finding everyday oddities. I write down strange bits of overheard conversations, or images that strike me. I once heard a man on the bus say to the driver that he felt like his whole body was burning, and I made an essay out of that. My neighbor told me one day that a river runs underneath our street (I’m still not even quite sure what he meant), and I wrung an essay out of that. A few weeks ago, I came home to find the sky on my street full of bubbles. It took me several minutes to find the child using a bubble machine up on a high balcony, but it didn’t matter — the image of a sky full of bubbles stuck. I never really know what to do with these oddnesses, or what meaning or synchronicity I will find, but I enjoy the process of trying to find it. Like VanAuken’s essay, I think our lives are built on these small moments as much as the big ones, so I am always fascinated by that smallness.

CD: Aside from JK Rowling, who are some writers who you love and/or who inspired you to become a writer?

JK: I think I’m strange in that I rarely felt like I had to be a writer or that I wanted to be just like so-and-so. I loved (and love) reading so much that I was always writing, too, from a very early age. They seemed like two processes that went together, and I don’t remember ever making the conscious decision to be a writer. I just wrote — mostly terrible stories about finding baby deer in the woods and keeping them as pets. As a young reader I loved Brian Jacques’s Redwall series (for its lavish food descriptions and intricate plotting—kind of like Game of Thrones for kids), and Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women (for the characters), and as I got older I loved Lolita (for its language) and Middlesex and Margaret Atwood and Toni Morrison, even if I was still learning to understand them. By far the biggest influences on me as an essayist have been Eula Biss (for her braided and fragmented essays), and Ryan Van Meter (who is a sensory detail genius), and most especially, Jo Ann Beard. Her book The Boys of My Youth is the book of nonfiction I return to most often. Her voice, her rendering of young adulthood, and her interrogation of memory is something I aspire to with everything I write.

CD: Which Harry Potter house would you be in and why?

JK: I spent most of my life thinking I was a Ravenclaw (brainy, loves books, etc. etc.), but as I’ve grown up I’ve started to grow into and recognize my true Hufflepuff nature (where Pottermore has also placed me). I tend to associate being a Hufflepuff with the kind of work ethic I associate with being Midwestern, and my introvert tendencies also feel very Hufflepuff. I love books, but more as a reader than as a scholar. If I had to enter a common room with a riddle, I’d be trapped outside forever.

CD: What’s next for you?

JK: I’m taking spring 2018 off from teaching in order to do a bit of book touring for Life Lessons Harry Potter Taught Me and I’m also working on revising my second book. It’s a personal essay collection called (for now) Tiny Disasters, and explores the way disasters (large and small, natural and political and personal) and the ways we try to handle them shape who we are. I also have a very large to-be-read stack I can’t wait to get to, and some Harry Potter movies to rewatch. Thank you again for this opportunity!

**

Jill Kolongowski is a nonfiction writer and professor living in Northern California. She is the author of the essay collection Life Lessons Harry Potter Taught Me (Ulysses Press, 2017). She received her MFA from Saint Mary’s College of California, and is also the managing editor at YesYes Books. Jill has been a fellow at the Artist Artsmith Residency, Lit Camp, and the Squaw Valley Community of Writers. Her essays have won Sundog Lit’s First Annual Contest series and the Diana Woods Memorial Prize in Creative Nonfiction at Lunch Ticket magazine. She is a Hufflepuff who grew up in Michigan.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Sydney Cohen spoke with David S. Rubenstein about his creative process, being a renaissance man, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Sydney Cohen spoke with David S. Rubenstein about his creative process, being a renaissance man, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Sydney Cohen talked with author Mike Harvkey about his book In the Course of Human Events, Midwestern masculinity, the role of the cliché, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Sydney Cohen talked with author Mike Harvkey about his book In the Course of Human Events, Midwestern masculinity, the role of the cliché, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Carrie Dudewicz talked with author Jill Kolongowski about her book Life Lessons Harry Potter Taught Me, how to juggle writing, editing, and teaching, her becoming a nonfiction writer, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Carrie Dudewicz talked with author Jill Kolongowski about her book Life Lessons Harry Potter Taught Me, how to juggle writing, editing, and teaching, her becoming a nonfiction writer, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Carrie Dudewicz talked with author Dan Beachy-Quick about his book Of Silence and Song, the formative experience of reading Moby-Dick, writing in the midst of family, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Carrie Dudewicz talked with author Dan Beachy-Quick about his book Of Silence and Song, the formative experience of reading Moby-Dick, writing in the midst of family, and more.