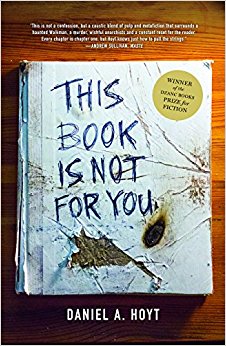

Midwestern Gothic staffer Carrie Dudewicz talked with author Dan Hoyt about his book This Book Is Not For You, experimental and fragmented writing, the literature of Rock and Roll, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Carrie Dudewicz talked with author Dan Hoyt about his book This Book Is Not For You, experimental and fragmented writing, the literature of Rock and Roll, and more.

**

Carrie Dudewicz: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Dan Hoyt: In 1988, I did a reverse Gatsby: I left the East Coast (Massachusetts) to go to the University of Missouri, where I completed a bachelor’s and stayed for a master’s. While at Mizzou and right after, I worked at both of the daily papers in Columbia, Missouri: The Daily Tribune and the J-School-run Missourian. I taught for a semester in Romania, and I lived in Binghamton, New York, for a year and a half or so, but since 1988, those are the exceptions, and I’ve mostly been a Midwesterner for my entire adult life: In the 1990s, I worked at two other Midwest newspapers (The Kansas City Star and The La Crosse Tribune), I got my PhD at the University of Kansas in the early oughts, I taught for six years at Baldwin-Wallace University in Ohio, and now I’m an associate professor at Kansas State University. I’ve got the golden handcuffs, so Manhattan, Kansas, is probably where I’ll spend the rest of my days. I’m the aesthetic and intellectual product of large public Midwestern Land Grant universities, and I’m so grateful for that. The Midwest made me a journalist. The Midwest made me a fiction writer. The Midwest made me a teacher. I don’t even say “cah” for “car” much anymore.

CD: You’ve spent much of your life in the Midwest. How does living in this region influence how and what you write?

DH: I write about the fucking messed-up and wonderful lives we have here, just like on the coasts. I write a lot of Midwest realism and Midwest magical realism, too, like my story where a man gets decapitated at a Burger King (the one right here in Manhattan, Kansas, actually) and then both halves of his body live on. A lot of people on the coasts don’t know that, that we have supernatural powers out here and that we live and bleed and we listen to punk rock in the basements of homes of very cool people and we make art and we wash out as purple politically and we give some of that blood to people in need and we plug into the internet and we drive faster than Springsteen and then we die here and we die a little bit every day, like everybody everywhere, and I don’t know what that really means, except our lives are messy and complex and not at all flat or boring or worth being fucking flown over, so I try to tell stories of those lives: of the 21st-century Midwesterners being caught looking silly on security cameras and trying to be rappers and trying to love without getting too fucking hurt. These are my people because I am these people. Neptune, the first-person narrator of This Book Is Not for You, has spent all but a couple of weeks of his life in Missouri and Kansas. He’s an anti-racist skinhead, and a punk, and a reader, and a writer, and he has a criminal past, and he’s an alcoholic, and he flails at love, and he tries, and he does stupid shit, and he’s haunted by ghosts, and he belongs to Lawrence, Kansas, and all of him belongs to this land. He belongs to Bloody Kansas. I don’t know — did I answer this one? Sort of maybe?

CD: This Book Is Not For You is a fascinating combination of multiple genres, told in a chain of “first” chapters. What inspired you to write such an experimental novel? How did that experience compare with writing more in more traditional forms?

DH: Oh, man, I’m going to answer the second question first, perhaps in a clever attempt to evade the first question. I started this book in 2003, when I lived in Lawrence, Kansas, and I didn’t finish it until 2014, and if it hadn’t been experimental and fragmented, I don’t think I could have finished it. I kept putting it down and picking it up and letting it sit for years, but because I was writing Neptune’s voice in these small bursts — in some ways I think of them like punk songs, short, fast, loud rude — I could summon him up somehow. He’s lived with me a long time. That’s how he thinks. That’s how he works. With more traditional forms, well, with short stories I tend to write in fragments too, but there’s a stronger process of sewing them together, of trying to hide the ragged seams. Neptune’s all ragged seams: they can show. Okay, now, that first question: I’m not sure what inspired me to write an experimental novel, except the book was born in this experimental town, in Lawrence, Kansas, a place that belonged to Native Americans and to abolitionists and to rock and rollers back in the day when it was going to be the next Seattle and to William Burroughs who lived there and to all the folks hanging out at the Replay Lounge. I wrote some of the first snippets on bar napkins, on the back of junk mail. I knew I wanted the voice to be punky, to challenge the reader. Man, that was a long time ago. I suppose something inspired me.

CD: Early reviewers say that the structure of the story, being told in only chapter ones, acts like a reset to the reader. Where did you get the idea to do this? Does this novel require that reader reset? If so, why?

DH: Yeah, I think there’s a really nice blurb that says there’s a reset for the reader on every page or chapter, but although I think that blurber is an incredibly astute judge of literature (Thank you, Andrew F. Sullivan! He was one of the judges of the Dzanc Fiction Prize, and because of his kindness and generosity — along with Kim Church and Carmiel Banasky—Neptune got to live a life in other readers’ heads. I’m so, so grateful to y’all), I don’t think the book resets. Neptune typically — eventually! — picks up where the last chapter left off, but, of course, the bigger point is that Neptune himself wants a reset: he doesn’t want to write the book or can’t write the book or can’t quite open up, but despite all this he still tries, and he tries to stop doing shitty things, and he tries to escape from his past, and each new chapter of course is something new, a fresh start. I think this idea came because, oh, hell, I think because it was fun?

CD: Similarly, was one experimental element more difficult to write than another? Was one more enjoyable?

DH: So many parts of it were enjoyable. It was superfun to bring in the ghost animals, and it was superfun to be snarky with the reader, and it was superfun to get all meta on the reader’s ass, and it was superfun to add the inside jokes and the noir elements and the Ghost Machine, which is a haunted Sony Walkman. Man, it was all fun! Which, I have to tell you, is so much easier to say and actually believe when the book is finished and printed!

CD: Are there specific experimental novels that inspired you? If so, which ones?

DH: Well, there are all those folks who did and are doing metafictional type stuff, and she hasn’t written a novel (at least that I now of), but I admire Kelly Link’s amazing prose and her sheer bad-ass bravado: Fuck yeah! Throw a zombie in! Apparently, too, there’s some sort of moment in House of Leaves that says “This book is not for you,” and the weird thing is, I’ve tried to read that book, and it just doesn’t kick into gear for me (that clutch just grinds), and I didn’t even know about the reference until after This Book Is Not for You was published, so I think the answer here is maybe? But, no, definitely not House of Leaves.

CD: As a professor at Kansas State University, how does your teaching influence your writing career and vice versa?

DH: Well, I love my students, and their work means a great deal to me, and because of that, during the school year, I spend a lot more time on their writing than on mine, but that’s kind of a shitty way to start here, so, well, shit, I get to be engaged in stories all the time, to think about narrative, to meet strange and wondrous characters that I would never create myself. I get to be inspired by my students, and I get to be energized by their hope and their possibilities. I try not to let my own writing influence my teaching beyond that I think people should try to do their damned best to write the richest versions of their own stories, the ones they want to tell, the ones they need to tell.

CD: You do a lot of teaching about literature and rock and roll. What drew you to this subject? How is rock and roll (generally) written about in fiction?

DH: I’ve been a rock and roll fan since my age was in single digits, but I probably got into rock and roll novels in my 20s. It’s a genre that allows for all kinds of cool interactions between form and meaning. My students seem to think that rock and roll literature is mainly about bands that fail, and, okay, they have a point there, but the literature of rock and roll does so many interesting things, like let us observe a really close friendship between a brother and sister (in Stone Arabia), or let us think about what being a “real” punk means (in A Visit from the Goon Squad). I’ve been putting together the Rock and Roll Reading at AWP (the fifth-annual will take place in Tampa), and it’s great, and everyone reads a piece that’s only as long as a song — just a few minutes — and let me tell you, the literature of rock and roll can do any damn thing it pleases. It’s up to the singer. Just sing loud, even if you can’t even sing.

CD: Is there a specific time of day you write best? If so, what is special about that time?

DH: I am a believer in writing pretty soon after you get up, so that the day doesn’t swallow you up along with your chance to write, and so that you can go through that day knowing you’ve written, that you’ve done it, and you, you my goddamn son, you do not have to feel guilty. But I teach and really care about it, and we have a 13-month-old, and the internet announces a fresh new catastrophe every second in 2017, so I’m fucking busy all the time, and accordingly I don’t have a special time to write, not really. I try to grab whatever I can. I’m 47 now, which feels ancient (thanks again, year 2017!), so all time feels special. I’ll take any hours you’ve got, minutes even.

CD: What’s next for you?

DH: Fiction-wise, I’m working on two novels, a realistic one set in Manhattan, Kansas, on Fake Patty’s Day (a day when students often begin drinking at 6 in the morning) and a more magical one set during the first 100 days or so of the Trump administration. I’m also working on a nonfiction book about the 1991 Fifth Down Game, when the officials made a mistake, and Colorado beat Missouri with an extra down on the final play of the game: It’s about the growth of big-time college football and mistakes and psychology and leadership. Life-wise, during the winter break, I’ll be roughhousing with Sey, our son, reading a stack of novels, playing some new vinyl, listening to bands at Manhattan’s Church of Swole, cooking some meals, taking walks, and calling my elected representatives: I’ll be yelping at them. I’ll be making New Year’s resolutions. I’ll be making up people who don’t exist, and, you know, they’ll feel alive.

**

Dan Hoyt’s debut novel, This Book Is Not for You, won the inaugural Dzanc Fiction Prize and was published on November 7, 2017. Dan’s first short story collection, Then We Saw the Flames, won the 2008 Juniper Prize for Fiction. Dan’s stories have appeared in The Sun, The Iowa Review, The Missouri Review, and other literary magazines. Dan teaches creative writing, mainly fiction, and lit classes, such as The Literature of Rock and Roll, at Kansas State University.

We are beyond thrilled to share with y’all that MG Press book A Woman Is A Woman Until She Is A Mother was chosen as one of Entropy magazine’s “Best of 2017 Nonfiction” titles! We’re so proud of Anna Prushinskaya, and so honored that she trusted us with her beautiful collection of essays. Join us in saying congrats to

We are beyond thrilled to share with y’all that MG Press book A Woman Is A Woman Until She Is A Mother was chosen as one of Entropy magazine’s “Best of 2017 Nonfiction” titles! We’re so proud of Anna Prushinskaya, and so honored that she trusted us with her beautiful collection of essays. Join us in saying congrats to

Midwestern Gothic staffer Carrie Dudewicz talked with author Dan Hoyt about his book This Book Is Not For You, experimental and fragmented writing, the literature of Rock and Roll, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Carrie Dudewicz talked with author Dan Hoyt about his book This Book Is Not For You, experimental and fragmented writing, the literature of Rock and Roll, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Kristina Perkins talked with author Holly Amos about her poetry collection Continual Guidance of Air, her obsession with experience, finding her community, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Kristina Perkins talked with author Holly Amos about her poetry collection Continual Guidance of Air, her obsession with experience, finding her community, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Marisa Frey talked with author Tatiana Ryckman about her book I Don’t Think of You (Until I Do), translating longing to written word, shorter-length publications, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Marisa Frey talked with author Tatiana Ryckman about her book I Don’t Think of You (Until I Do), translating longing to written word, shorter-length publications, and more.

We’re thrilled to announce our nominees for the 2017 Pushcart Prize!

We’re thrilled to announce our nominees for the 2017 Pushcart Prize!