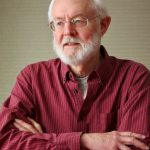

Photo credit: Jamieson Fry

Midwestern Gothic staffer Meghan Chou talked with author T. C. Boyle about his book The Terranauts, climate change, reality TV, and more.

**

Meghan Chou: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

T. C. Boyle: I discovered it on Route 80 after crossing the Hudson for the first time in my life. I was twenty-five at the time, with a girlfriend, a dog and two cats. We settled in Iowa City for five and a half years, where I earned my M.F.A. and Ph.D. degrees.

MC: How did your time in Iowa at the University of Iowa and Iowa Writers’ Workshop influence you as a writer?

TCB: While I haven’t written much about my time there, it was formative. Not only were the bars and music scene lively beyond compare (Duck’s Breath Mystery Theatre was doing its thing at Gabe & Walker’s then), but the intellectual ferment just began to produce a fine ripe old vintage deep inside me. I saw most of my heroes onstage—Lenny Michaels, Kurt Vonnegut, William Styron, Ray Carver, Stanley Elkin, Grace Paley and a hundred others—and plunged deep into the literature of the nineteenth century. See my essay, “This Monkey, My Back,” and, more recently, my short story, “The Night of the Satellite” for the flavor of Iowa.

MC: In The Terranauts, a group of individuals agree to live in a contained biodome in Arizona. E2, the nickname for this isolated dome, is a social and scientific experiment, testing alternative habitats should the climate change problem escalate. What real-world experiments did you draw inspiration from for The Terranauts?

TCB: The Terranauts jumps off from the actual Biosphere II experiment of the early 1990s. It was meant to last one hundred years, but only made it through two and a half. That’s where I stepped in.

MC: What message does The Terranauts convey about how we as a world and country should approach climate change?

TCB: The message is for the reader to interpret. Novelists do not explain; they entertain and provoke. That said, I like what Elizabeth Kolbert had to say about the latest Mars venture—that is, while it is all but impossible to recreate a self-sustaining environment that has had millions of years to evolve, it shouldn’t be quite as hard to pay more attention to the one that sustains us.

MC: The inhabitants of E2, deemed the Terranauts, follow the motto, “Nothing in, nothing out.” How is this theme echoed throughout different aspects of the book and in the real world with regard to climate change?

TCB: Obviously E2 is a microcosmic world. Our water can take years to percolate through the ground and wind up in our glasses; in E2, it takes days. Similarly, no artificial scents or products were allowed inside, because the Terranauts would be absorbing them in their tender cells much more quickly than that process happens out here.

MC: Not only does the omniscient Mission Control observe the inhabitants of E2, but cameras also broadcast their daily activities to the greater public. How does this constant surveillance and high-profile publicity affect the behavior of the characters in E2 and the way you chose to examine human nature?

TCB: In some ways, Biosphere II was the original reality TV show. I exaggerated Mission Control’s oversight for my own purposes. Big Brother, indeed. Hello, God!

MC: This constant surveillance and the public’s obsession with the happenings of E2 sounds similar to the setup of some reality television shows. What truths did you want to bring to light about the business and attraction of reality television?

TCB: Again, we must leave interpretive questions for the audience. I do find it interesting that the scenarios I’ve written about in the past are now codified as reality TV (see “Peep Hall” and the naked-in-nature section of my global-warming novel, A Friend of the Earth).

MC: Three characters narrate The Terranauts: Dawn Chapman, an environmental scientist; Ramsay Roothorp, a flirt; Linda Ryu, a candidate not selected for the mission. What perspective does each narrator bring to the story? How do you, as a writer, decide how many narrators are needed to best tell a story?

TCB: I am always trying to do something different with any given narrative. In this case, I have experimented with three first-person narrators. If the experiment works, I believe it brings great intimacy to the narrative—each character is essentially soliloquizing to the reader and each has a very different perspective from those of his colleagues.

MC: What’s next for you?

TCB: My new collection, The Relive Box and Other Stories, hatches in October. I am two-thirds of the way through the next novel, which I hope to finish by the end of the year. Since it is about the early days of LSD, I am hoping my publisher will include a tab of blotter acid on the title page of each copy.

**

T. Coraghessan Boyle is the author of twenty-six books of fiction, including, most recently, After the Plague (2001), Drop City (2003), The Inner Circle (2004), Tooth and Claw (2005), The Human Fly (2005), Talk Talk (2006), The Women (2009), Wild Child (2010), When the Killing’s Done (2011), San Miguel (2012), T.C. Boyle Stories II (2013), The Harder They Come (2015) and The Terranauts (2016). He received a Ph.D. degree in Nineteenth Century British Literature from the University of Iowa in 1977, his M.F.A. from the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop in 1974, and his B.A. in English and History from SUNY Potsdam in 1968. He has been a member of the English Department at the University of Southern California since 1978, where he is Distinguished Professor of English. His work has been translated into more than two dozen foreign languages, including German, French, Italian, Dutch, Portuguese, Spanish, Russian, Hebrew, Korean, Japanese, Danish, Swedish, Norwegian, Lithuanian, Latvian, Polish, Hungarian, Bulgarian, Finnish, Farsi, Croatian, Turkish, Albanian, Vietnamese, Serbian and Slovene. His stories have appeared in most of the major American magazines, including The New Yorker, Harper’s, Esquire, The Atlantic Monthly, Playboy, The Paris Review, GQ, Antaeus, Granta and McSweeney’s, and he has been the recipient of a number of literary awards, including the PEN/Faulkner Prize for best novel of the year (World’s End, 1988); the PEN/Malamud Prize in the short story (T.C. Boyle Stories, 1999); and the Prix Médicis Étranger for best foreign novel in France (The Tortilla Curtain, 1997). He currently lives near Santa Barbara with his wife and three children.

We’re so excited to announce that A Woman Is a Woman Until She Is a Mother is available now! Please join us in saying happy pub day to the incredible Anna Prushinskaya and her nonfiction collection about motherhood and its complexities!

We’re so excited to announce that A Woman Is a Woman Until She Is a Mother is available now! Please join us in saying happy pub day to the incredible Anna Prushinskaya and her nonfiction collection about motherhood and its complexities!

Milton Bates’ piece “Tragedy at Presque Isle” appears in

Milton Bates’ piece “Tragedy at Presque Isle” appears in

Midwestern Gothic staffer Marisa Frey talked with author Kathleen Rooney about her book Lillian Boxfish Takes a Walk, changing the world through writing, balancing fact and fiction, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Marisa Frey talked with author Kathleen Rooney about her book Lillian Boxfish Takes a Walk, changing the world through writing, balancing fact and fiction, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Meghan Chou talked with author Nick White about his book How to Survive a Summer, exploring nontraditional queer spaces, outsmarting the hurdles to keep writing, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Meghan Chou talked with author Nick White about his book How to Survive a Summer, exploring nontraditional queer spaces, outsmarting the hurdles to keep writing, and more.

John Yohe’s piece “The hunter down the road” appears in

John Yohe’s piece “The hunter down the road” appears in  Midwestern Gothic staffer Meghan Chou talked with author Kristen Radtke about her book Imagine Wanting Only This, visiting ruins around the globe, the unique genre of graphic memoir, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Meghan Chou talked with author Kristen Radtke about her book Imagine Wanting Only This, visiting ruins around the globe, the unique genre of graphic memoir, and more.