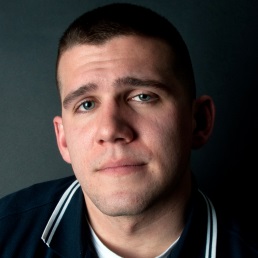

Contributor Spotlight: Anita Koester

June 13th, 2017

Anita Koester’s piece “Preserved Embryos” appears in Midwestern Gothic‘s Winter 2017 issue, out now.

Anita Koester’s piece “Preserved Embryos” appears in Midwestern Gothic‘s Winter 2017 issue, out now.

What’s your connection to the Midwest, and how has the region influenced your writing?

I was born and raised in Chicago so I’m a city girl through and though. The grit and hardness of our sprawling metropolis definitely enters and alters my work, though since I became a writer, I’ve been fortunate to travel to residencies in Nebraska and Michigan and my time there connected me to the countryside. A month nestled in the flat cornfields of Nebraska in the middle of nowhere will tug the city out of you. There I felt my exoskeleton dissolving until I could simply experience the silent beauty of a starlit night or whittle away days writing in a dilapidated barn.

I suppose my view of the countryside is entirely romantic while I turn a more critical and emotional eye on Chicago which for me is forever entangled and woven with my family history. Chicago is where my immigrant grandparents settled in early adulthood and worked hard to build a better life and a better city. My mother continued this tradition, but my father was corrupted by organized crime and perhaps by the way Chicago mythologized its criminals, he lived a secret life as a thief and bank robber until he was imprisoned. Those choices he made affected my life profoundly and I’m still trying to unpack all that hurt and loss through my writing.

What do you think is the most compelling aspect of the Midwest?

For me, it’s the people, Midwesterners don’t care about how the outside world perceives them, our facades, when or if we build them, are half-hearted at best. Designer labels and the moneyed classes are not celebrated here, we’re more like people in a Frank Capra film, and I like that, it keeps me humble. It keeps me real. There is a healthy lack of pretension in the Midwest. There is also a lot of empathy here, I think Midwestern people in general are family oriented; they want to be there for the people they love. I don’t want to say that the dreaming here is smaller, because in America smaller is not always recognized as better, but Midwestern dreaming tends to have a limited radius.

How do your experiences or memories of specific places—such as where you grew up, or a place you’ve visited that you can’t get out of your head—play a role in your writing?

Well, it’s always the places I can no longer visit that I’m drawn to, like my grandparent’s home in Andersonville. I’ve been working on some poems about that house and how since it was torn down to make way for a new condo building it only exists in memories as this ghostly structure that once stood but no longer stands. I suppose in some ways that ends up representing my grandparents, and perhaps even their values, some of which are outdated.

I’ve come to realize many of my favorite poems involve houses, Neruda has this gorgeous poem where he describes a destroyed dining room where nevertheless roses are still delivered, indicating that someone still believes there is love or someone to love there. I tend to feel like my poems about places are like that, like a late delivery of roses. I think what people don’t always see in poems are that even when the poet displays hurt and anger there is a kind of devotion indicated by their act of writing that poem.

Discuss your writing process — inspirations, ideal environments, how you deal with writer’s block.

I have yet to write in my ideal environment, though some have come close. I wrote “Preserved Embryos” in an old Michigan farmhouse that butted up against a nature preserve. I knew I wanted to write about something I saw recently at a museum that had touched me, unsettled me, as well as stirred up my anxieties and there was this petite bedroom teeming with another writer’s books, it was this quiet sanctuary, a place in which you could feel a writer’s spirit, and in that room the poem came gushing out. It became my writing room for the rest of the residency. Now, if that window had overlooked a lake that would have been my ideal environment, the mysteriousness of water and aquatic life is always such a fitting metaphor for writing.

As far as writer’s block, I’ve been lucky so far, I think because I spent 10 years not being a writer even though it was this secret desire of mine, that since I started writing, I haven’t been able to stop. But if it does dry up, if I were to use up even the smallest nuggets of memory, then I’d better get living, or reading, reading usually works for me. I read for an hour and I’m anxious to write.

How can you tell when a piece of writing is finished?

I’m the wrong poet to ask, I’m wrong about this too often. A poem for me is rarely done until it’s published in a book, and I’ll work on them right up until the galleys are done. I submit work I think is finished, but then a month later I see the flaws and I completely rewrite it. Though occasionally, there are these “ah, ha poems” that are usually written in one sitting and when I finish them I feel the urge to celebrate, and those are the rare poems I never rewrite. Those are also usually my personal favorites, not because I didn’t have to spend days, weeks, or months on them but because I knew they felt right, felt unalterable. Otherwise, I tinker and reorder and rewrite endlessly.

Who is your favorite author (fiction writer or poet), and what draws you to their work?

I have a lengthy list of favorite writers, so each year I focus in on the one or two who seem to be influencing my work the most. This year I felt pulled to both Larry Levis and Sharon Olds. Sharon Olds in part because I had the pleasure of workshopping with her, and when you have a chance to spend time with a poet you idolize, their work becomes more accessible. When I went back to visit her work I could actually hear her soft yet commanding voice as I read, I could hear that four beat rhythm and the way she pauses and says “hmm” just before she says something brilliant. I admire her ability to stay close to a single moment in all its exacting detail and yet retain the awareness of how her scene fits into larger thematics. I can only hope to one day be capable of that kind of nuanced recording of life.

And Larry Levis’ work, especially in Elegy, gives me a kind of permission to allow more organized chaos into my work, let lines and images unravel, to be abstract or prosaic and then come back to the narrative or musical thread. There is this expansive quality to his elegies that makes each poem feel epic, symphonic really, and no matter how many times I read them they continue to excite me.

What’s next for you?

Well, I have two chapbooks coming out in the first half of 2017, Arrow Songs will be coming out with Paper Nautilus in the next few months, and Apples or Pomegranates will be out in the spring with Porkbelly Press. In the meantime, I will continue to write and sculpt my full-length manuscript and I hope that when I’m finally satisfied it will find the right publisher. I’ve felt so fortunate to work with such supportive chapbook presses, I can only hope that my full-length will find an equally loving home.

Where can we find more information about you?

I’m fairly good at updating my website – anitaoliviakoester.com! Thanks for asking!

During the summer of 2015 we introduced our Flash Fiction contest series, and we’re thrilled to be continuing it this year! (And you can read all of our winners from

During the summer of 2015 we introduced our Flash Fiction contest series, and we’re thrilled to be continuing it this year! (And you can read all of our winners from  Our 2017 Flash Fiction Contest is sponsored by Audible. Get a free 30-day trial and 2 books, on us when you sign up.

Our 2017 Flash Fiction Contest is sponsored by Audible. Get a free 30-day trial and 2 books, on us when you sign up.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Megan Valley talked with poet Sjohnna McCray about his collection Rapture, dreaming of being a dance DJ, being raised by a Vietnam vet, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Megan Valley talked with poet Sjohnna McCray about his collection Rapture, dreaming of being a dance DJ, being raised by a Vietnam vet, and more.

Once again, Midwestern Gothic will be at this year’s Printer’s Row Lit Fest in Chicago (Saturday-Sunday June 10-11).

Once again, Midwestern Gothic will be at this year’s Printer’s Row Lit Fest in Chicago (Saturday-Sunday June 10-11). Make sure to check out another interview with Keith Lesmeister, now up on Michigan Quarterly Review‘s blog site! Keith discusses

Make sure to check out another interview with Keith Lesmeister, now up on Michigan Quarterly Review‘s blog site! Keith discusses

Jessica Kashiwabara’s nonfiction piece “In the Middle” appears in Midwestern Gothic‘s

Jessica Kashiwabara’s nonfiction piece “In the Middle” appears in Midwestern Gothic‘s

Midwestern Gothic staffer Kristina Perkins talked with author Thomas Mullen about his novel Darktown, crime in history and present time, the choices a writer must make, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Kristina Perkins talked with author Thomas Mullen about his novel Darktown, crime in history and present time, the choices a writer must make, and more.

Jason Arment’s piece “VA Mental Health Waiting Room” appears in Midwestern Gothic‘s

Jason Arment’s piece “VA Mental Health Waiting Room” appears in Midwestern Gothic‘s