Interview: Abby Geni

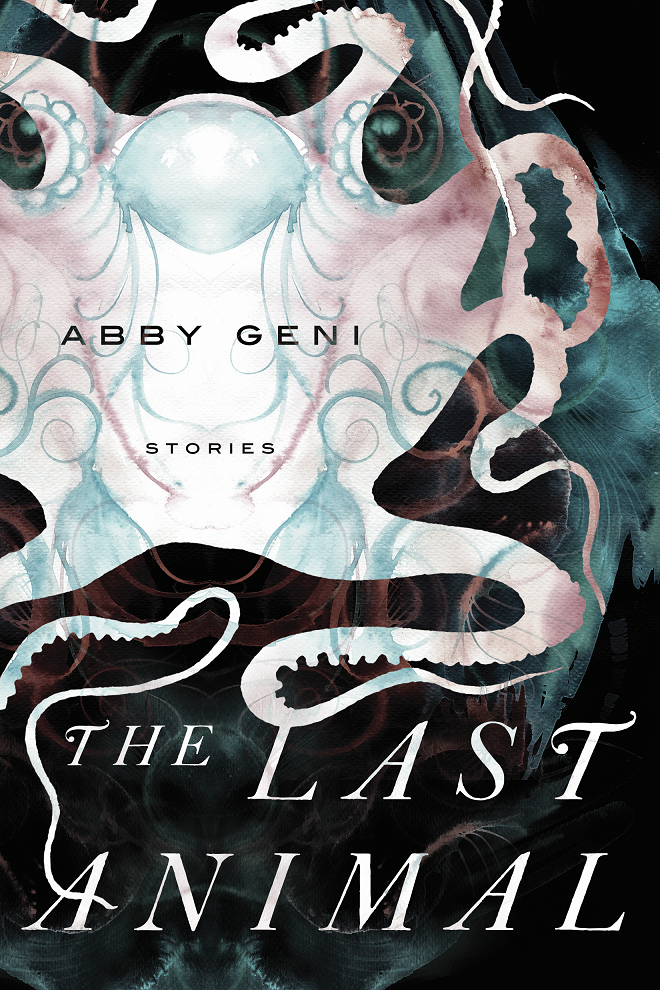

Midwestern Gothic staffer Katie Marenghi talked with author Abby Geni about her debut short story collection, The Last Animal, the relationship between people and nature, the extreme seasons of the Midwest, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Katie Marenghi talked with author Abby Geni about her debut short story collection, The Last Animal, the relationship between people and nature, the extreme seasons of the Midwest, and more.

**

Midwestern Gothic: First things first, tell us about your Midwestern connection. How has the region influenced your writing?

Abby Geni: In writing The Last Animal, I wanted to talk about the myriad ways in which human beings connect to nature. To fully explore that idea, I did my best to scatter the stories across different characters: an aquarist, an ostrich farmer, a gardener, a dog owner. And of course, place was a consideration too. I wanted as many different locations as possible. Most of the stories in the collection are set outside the Midwest—in Maine, Arizona, California, Mexico, as far away as the Nigerian delta.

However, it’s no coincidence that those stories that are closest to me—to my own experience—are set in Iowa, Michigan, and Chicago. I’m a Chicagoan, born and bred. That’s woven into me. The Midwest is where my family is, my home, my heart.

MG: You say in your self-interview that you’ve been writing since a very young age. How has your writing changed over time?

AG: I recently stumbled on a very old story of mine. I was leafing through a photo album when I found a letter from my grandmother. She passed away last year, though she had been disappearing into Alzheimer’s long before that. She must have tucked the letter into the album and forgotten about it. In her note, she told me that when I was twelve years old, I sat at the ancient, creaky typewriter in her apartment and wrote a story while she was cooking dinner for me. She loved the story so much that she saved it. I found it tucked into the back of that same envelope, folded and yellow and soft with age. It was an astonishing thing to come across: a message from my lost grandmother, a message from a lost version of myself.

In reading the story, however, what surprised me most was how my voice was already there. The structure was chaotic, and I used far too many adjectives and adverbs (still an unfortunate tendency of mine), but it was recognizably my writing, even then.

MG: Your writing style is self-described as solitary. How was that challenged when you were at the Iowa Writer’s Workshop?

AG: Workshop has never been the easiest thing for me. I like to work alone until a new story is as strong as I can make it—a process that can take me months or years. In an ideal world, I will have the luxury of sitting with a piece, walking away from it, having sudden realizations about it in the middle of the night, revisiting it, burnishing it, polishing it. Once I’m convinced that there’s nothing more that I can do on my own, then I feel comfortable sharing it. At that stage, I do love to get feedback, and I’m happy to revise and make changes. Working with an editor for The Last Animal has been a wonderful and collaborative process.

But in a workshop, of course, you don’t have the luxury of operating at your own timetable. You have to turn in pieces when they’re due, regardless of whether you feel ready. Getting feedback on a raw and unfinished story, for me, was a bit like fencing without armor. I walked away bruised and shaken. I wouldn’t give back my time at Iowa for anything—I learned more than I can say, made wonderful friends, worked with tremendous teachers—but after I graduated, I took three years off, in which I didn’t write a word. It took me that long to clear all the other voices out of my head and go back to writing on my own schedule, in my own way, alone.

MG: Animals feature heavily in your work, particularly your most recent book, The Last Animal. What draws you to them as subject matter?

AG: Hmmm…. I think some people never get over the loss of magic. For children, the world is magical. Santa Claus and the Tooth Fairy and the thousand invisible, imaginary worlds that exist just inside every toy, every storybook, every game of Let’s Pretend. Some children grow out of that state quite naturally, but for others, the loss can be gut-wrenching. It was gut-wrenching for me. I remember the uncertain period on the cusp of puberty, when I could no longer disappear completely inside the books I was reading, when I picked up my toys and they seemed small, lifeless, unimportant. I remember thinking, essentially, that adulthood seemed like a pretty big rip-off.

But animals are magical. Animals consoled me for the loss of those thousand imaginary worlds. After all, albatrosses can sleep on the wing. Whales can perceive the magnetic currents in a wide, blue, undifferentiated ocean. Elephants can communicate by stomping their feet. There are animals that live in the rainforest canopy that never see the ground, and animals that live at the bottom of the ocean that never see sunlight. Cockroaches can survive for weeks after their heads are removed, breathing through other body parts. Salamanders can regenerate amputated limbs. And don’t even get me started on octopuses. I write about animals the same way children tell stories about ghosts or witches or fairies—because these creatures are strange, terrible, and wonderful beyond measure.

MG: The Last Animal focuses on the relationship between people and nature. What makes this relationship important to you?

MG: The Last Animal focuses on the relationship between people and nature. What makes this relationship important to you?

It’s the most important thing in the world. This morning I read news stories about the economy, the political stalemate in Washington, the red state/blue state cold war, gay rights, racism, abortion, the ever-increasing drift into some kind of technological dystopia. But none of these issues seems as vital to me as our relationship to nature. Nothing else affects—or challenges—our survival as a species. Climate change, super storms, the free fall of mass extinction, the death of the oceans. We’re pretty much at the end of days. The whole world should be pulling together to stop this. I don’t understand why it isn’t front-page news every single day.

MG: Historically, what do you think the Midwesterner relationship to nature is? Do you find that the humans-nature relationship changes region to region—that in some cases people are more receptive to nature, and in others, more indifferent to it? If so, why do you think that is?

AG: I love that question. I do think there’s something about the extremity of the seasons in the Midwest that awakens the mind. At the peak of both winter and summer, the radio announcers start to count the death toll—people who have been claimed by the weather. Winter is a ferocious thing in the Midwest; spring is a long, slow unfurling of the spirit; summer is vibrant, vicious heat; autumn is languid and mournful. You can’t help but be aware of nature when it’s always in flux around you.

Also, the Midwest is landlocked. That has an impact too—a feeling of being dug in, of putting down roots. Coastal places offer the illusion of movement, of an ephemeral life, the possibility for change. I do enjoy the ocean, but I prefer the sense of permanence of my home, where behind every hill there’s more earth, and more earth behind that, too. Earth stretching all the way to the horizon.

MG: Now you teach as well as write. How has being a teacher changed your own writing?

AG: More than anything, it’s taught me that there are a thousand ways in. Everyone comes to their writing differently. For instance, I prefer to write in the morning. I get better work done when I meditate before I sit down at my desk. And if I don’t take at least a couple days off each week from writing, I short-circuit completely. But that’s just me. My students all have different paths to the work. It irks me when I hear someone—particularly a writing teacher—say that all writers should write every day, or that all writers should vary where they work, or that all writers should work at a certain hour for maximum productivity. There are no rules that apply to all writers.

MG: What are you reading right now?

AG: I’m re-reading right now, actually. I do that a lot. If I love a book, I’ll read it at least a dozen times, trying to see how the author accomplished it, how each turn of phrase and scene and chapter was made. It’s a bit like excavating an architectural dig; each time I read, I remove another layer, first shaking off the surface soil, then tracking down through the loam, and finally revealing the bones.

But to answer your question, right now it’s The Animal Dialogues by Craig Childs—a strange, meditative gem of a book.

MG: What’s next for you?

AG: I’m hard at work on a novel. I was interested in writing literary fiction that plays with the typical mystery structure: a suspicious death, an enclosed environment, a limited number of suspects. As usual, I’m also exploring the relationship between nature and humankind, this time on an island chain in the Pacific Ocean, where a group of biologists is studying the wild and fascinating marine life. The novel touches on the vital issues of violence, healing, and great white sharks.

**

Abby Geni’s debut collection of stories, The Last Animal, was selected for the November 2013 Indie Next List and is one of the Debut Dozen, 12 titles chosen by a jury of booksellers as part of “Celebrate (With) Indies.” Abby is a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and a recipient of the Iowa Fellowship. Her stories have won first place in the Glimmer Train Fiction Open and the Chautauqua Contest. Additionally, her pieces have appeared or are forthcoming in Glimmer Train, Flaunt Magazine, Chautauqua, The Indiana Review, Confrontation, New Stories from the Midwest, The Fourth River, Iron Horse, and Crab Orchard Review, among others. She teaches at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and StoryStudio Chicago. She is hard at work on a novel.