Interview: Eliot Treichel

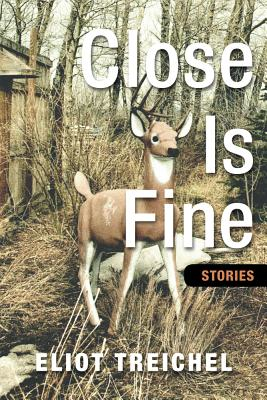

Eliot Treichel is a native of Wisconsin. He now lives in Eugene, Oregon, where he teaches writing at Lane Community College. His short stories have appeared in Narrative, Beloit Fiction Journal, CutBank, Passages North, Southern Indiana Review and other literary journals. He’s also written for Canoe & Kayak, Paddler, and Eugene Magazine. Close Is Fine (Ooligan Press) is his first book.

Eliot Treichel is a native of Wisconsin. He now lives in Eugene, Oregon, where he teaches writing at Lane Community College. His short stories have appeared in Narrative, Beloit Fiction Journal, CutBank, Passages North, Southern Indiana Review and other literary journals. He’s also written for Canoe & Kayak, Paddler, and Eugene Magazine. Close Is Fine (Ooligan Press) is his first book.

Midwester Gothic: First things first, tell us about your Midwestern roots.

Eliot Treichel: I’m a Wisconsin boy: born in Milwaukee, then moved north to the Fox River Valley, where I spent my grade school and high school years. After that I moved out west for college, but came back every summer—this time farther north, near the headwaters of the Wolf River. After college, despite proclaiming that I never would, I returned—the same place along the Wolf—and made it through a few more years. And even now, after more than a decade in the Pacific Northwest, Wisconsin still feels like the definition of home for me.

MG: What do you think defines this place?

ET: Holsteins. Corn Fields. Country roads laid out in a grid. Small towns with multiple bars and churches. Lutheranism. Red barns. Pheasants. Madness-inducing clouds of mosquitoes. Florescent orange clothing and deer hunting season. A certain kind of quietness—one that involves not complaining too much, or not speaking of things directly. Kettle holes and marshes. Lake Superior. Lake Michigan. The Mississippi River. Memories of cold. A coldness that does not come like it used to. Light manufacturing. The only publically owned professional football team. Bratwurst. Cheddarwurst.

Or maybe this: A few years back, I was home visiting my parents. This was early December, just after dark, half a foot of snow on the ground. I was driving on some frontage road, just coming home from a cheese outlet, if you can believe that. A car had slid off the road near an intersection. Another car had already stopped. Then I stopped. And within a few more minutes, several other cars had stopped, and we all worked together to push the car out of the drift and back onto the road. Afterwards, people were joking and laughing, dusting the snow off their pants, stomping it from their shoes. There was a Thank you, followed by a bunch of It was nothings, and then everyone left. As I drove off, I just had this very distinct feeling that that moment somehow epitomized Wisconsin. I can’t really explain it. I’m not sure how it would’ve played out in Oregon exactly, but I have the sense that it would’ve played out much differently—less casually, less joyfully, less cellphone free.

MG: One of the big things we focus on at Midwestern Gothic how overlooked the region is, both from a cultural/literary perspective. Agree? Disagree? If you agree, elaborate.

ET: I mostly agree. I think it’s changing some—that Wisconsin, and the Midwest in general, aren’t as overlooked as they once were. I’m not sure what kind of evidence I have to support that assertion, but that’s how it seems. I hope it’s true. I say overlook the overlookers.

MG: Personally, as a visitor to Wisconsin, I think it is a fantastic place for quirky, found objects tucked away off the beaten path. If you could take someone just one place in your home state, where would it be?

ET: My secret make-out spot.

MG: As a transplant to the Pacific Northwest, what was the process of tearing up roots and planting them back down like? Does it affect your work? How?

ET: There’s something wonderful about being in a place long enough to establish roots—a sense of community and familiarity and support. There’s also something wonderful in being like dandelion seed—aloft on the winds, dispersing. I think many of the characters in Close Is Fine are struggling between those two different ways of being. Maybe my move to the Northwest influenced that. The title story has its narrator fleeing. The last story in the collection, “The Golden Torch,” takes the other approach. That’s just in terms of geography. Emotionally, things go differently.

MG: Tell us something nobody else knows or might guess about you, if we might be so bold.

ET: I don’t really have a secret make-out spot.

MG: The stories in Close Is Fine involve a lot of everyman / everywoman characters, some who strive to escape their current situation (“On By,” “We’re Not That”) and some operate within the boundaries they’ve created for themselves. Is there something in particular that explains why some people tip one way over the other?

MG: The stories in Close Is Fine involve a lot of everyman / everywoman characters, some who strive to escape their current situation (“On By,” “We’re Not That”) and some operate within the boundaries they’ve created for themselves. Is there something in particular that explains why some people tip one way over the other?

ET: In terms of the characters, there’s nothing in particular—it was just how the stories felt they should go. In terms of real life, if I could explain why some people tip one way over the other, I’m pretty sure I’d be the author of several best-selling self-help books—another way of saying: much wealthier.

MG: What’s been your favorite part of the writing process?

ET: First drafts are tough for me. I often think that writing is chiefly a problem-solving exercise, and sometimes in first drafts I spend too much time trying to problem solve—trying to problem solve long before I have any idea of what the actual problems are, or could be. It’s bumpy, and there are backaches. Revision is generally more enjoyable. I like having something on the page, some sort of framework to work within, even though I almost always just rewrite and retype the whole thing. I also enjoy the part of the journey where I’m narrowing in on the voice of a story—the trying on of different syntaxes, different vocabularies, different ways of articulating a view. It is, in some ways, the intimate act of really getting to know a person.

MG: What lead you to choose your current publisher? What’s unique about what happens when an indie publisher / small press pair up with a first time author?

ET: Luck. Happenstance. The alignment of the stars.

Ooligan Press is unique in that they’re a non-profit teaching press—part of the Publishing Program at Portland State University. This affords both opportunities and disadvantages. Ooligan, and other small presses in general, have different risk thresholds—entirely different conceptions of risk, really. Better ones, I think. My book received a lot of care at Ooligan, more care and attention than it probably would’ve received at a large publisher. And by working with students, I also learned a great deal about how the publishing world works, something writers need to understand. Small presses also face real and big challenges—the challenges of small marketing budgets, of getting reviews written, of getting books on the shelves. It’s not easy. Big presses and small presses ultimately need the same thing: for people to buy books.

MG: What’s next for you?

ET: I’m working on a YA novel, or what I think is a YA novel. Or it’s an adventure novel with a teenage protagonist. Or something along those lines. I also want to get back to writing stories—where some fermentation has been taking place. Mainly, I just want to try and get better, to understand writing and life more clearly. My view of writing as problem-solving, at least to some degree, stems from when I was a teenager and read Edward Abbey’s Hayduke Lives!, and this very profound (to me) question (that was really more of a feeling) washed over me—this feeling that I’d never be able to ever comprehend how anyone could actually write a book, or how one could imagine a book. How does one do that? To a large extent, that feeling and that problem still plaques and inspires me. I just want to keep developing my understanding of all the possible answers to those questions.

MG: Where can people find out more about your projects?

ET: eliottreichel.com, or closeisfine.com.

MG: Sum up the Midwest in 100 characters or less.

ET: The ghosts and echoes of glaciers and immigrants.