Interview: Michael Perry

Midwestern Gothic staffer Katie Marenghi talked with New York Times bestselling author author Michael Perry about his autobiographical work, pig farming, being a father, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Katie Marenghi talked with New York Times bestselling author author Michael Perry about his autobiographical work, pig farming, being a father, and more.

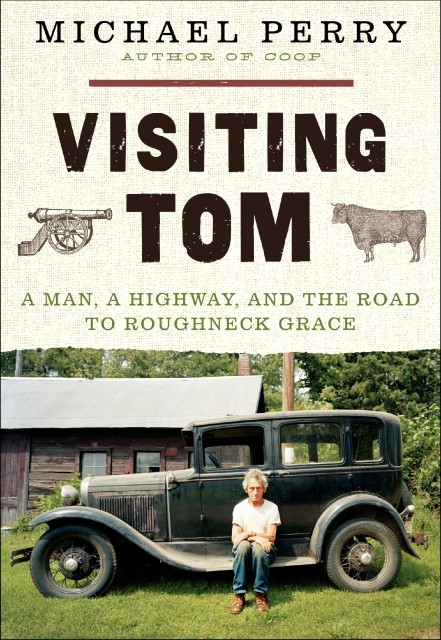

(Photo credit: Andi Stempniak, Leader-Telegram, Eau Claire, Wisconsin.)

**

Midwestern Gothic: First things first, tell us about your Midwestern roots.

Michael Perry: I was born in Wisconsin Rapids. My dad worked in the paper mills in Port Edwards. When I was two he bought a farm a few miles north of New Auburn, and thus I grew up a cheddar-head farm boy. Milking cows, cleaning calf pens, baling hay, logging in the winters.

MG: How do you feel the Midwest has shaped your writing?

MP: There is a residual stoicism coupled with a wry observational humor. For instance, nothing was funnier to the folks who raised me than nonfatal injury. If your buddy gets hit in the head with a monkey wrench and can still talk, well, that’s just hilarious. Also there is a certain tendency to hunch your back and get the work done without fancy clothes or drama. That said, any Midwestern memoir writer who invokes stoicism must then explain how he came to write page after page about his feelings.

MG: Some people would consider your childhood on a dairy farm in Wisconsin a somewhat quintessential Midwestern experience. What do you think characterizes the Midwest? What do you believe is the “Midwestern identity”?

MP: I believe that answer to that question is never constant. Depends on geography (the inner city Milwaukee experience is every bit as Midwestern as me standing in front of red barn beside a milk cow) and time (the Sioux and Ojibwe were Midwesterners before we were). And of course we are all being ineluctably drawn to a digital center…we may still eat lutefisk in the basement of the Lutheran church, but we are also mostly totally wired.

MG: Much of your work is autobiographical—how do you find inspiration in the everyday?

MP: I once spoke with the late Anthony Shadid—a man who put his life on the line in order to tell the stories of others—and he said one of the most destructive things about bombs and war and mortal strife was the loss of the simplest civilities. In particular he was referencing conversations he used to have over coffee in an Iraqi bookshop. We get so busy bashing each other over the head with the minutiae of the day that we forget: sometimes the most beautiful thing that can happen on any given day is for pretty much nothing to happen. Ultimately, if I have any hope for my writing, it is that it might somehow lead to some contemplation of the priceless quiddity of small moments. Then there is the fact that my everyday is filled with bonehead moves apparently relatable to a small but loyal—and apparently similarly afflicted—readership.

MG: So many of your close friends, relatives and neighbors play a part in your writing—has anyone ever complained about the way that you portrayed them?

MP:Yep. After Population 485 came out, the lady down at the gas station said the reason she didn’t tell her ex-husband about writing a few extra checks on his bank account was because he didn’t tell her about his girlfriend. So in an updated version of the book I told her side of the story. A guy’s gotta be able to go to the gas station.

MG: The subject of your latest book, Visiting Tom, is your neighbor, a man your website describes as “famous for leading a team of oxen in local parades.” Why do you think it’s important to tell the stories of people like Tom?

MG: The subject of your latest book, Visiting Tom, is your neighbor, a man your website describes as “famous for leading a team of oxen in local parades.” Why do you think it’s important to tell the stories of people like Tom?

MP: Because he and his wife represent the wit, intelligence and humanity of so-called “common folk.” Nothing common about them, even though their spirit abounds. The thing is, it abounds in quiet places. Not in the headlines or in the pageant of popular culture. They would never claim to have anything to teach the rest of us, but of course they do. I’m just blessed with the time to sit at their kitchen table and take notes.

MG: You have a varied background, including everything from pig farming to volunteer firefighting to nursing to performing alternately as a musician and humorist. How do you think your other pursuits have influenced your written work?

MP: I’m a writer neither by trade nor training—and often that shows. Grammar and punctuation, for instance, are not my forte. I’m also not expert or proficient at anything important like brain surgery or putting a crown on a gravel road. But I have done a lot of things and seen a lot of things and hung out with people of all persuasions and possess some combination of word masonry and echolalia that allows me to portray them with some baseline accuracy. I wish many times that I was more educated as a writer, that I had more of the academic underpinnings and understanding and technical proficiencies of some of the folks who have helped me become a writer (through both their work and informal conversations), but in the end I’ve been well-served by what is essentially a short attention span that precludes long-term employment.

MG: Your writing process is a very physical and hands on—you actually cut and paste the printed pages by hand. Why do you think this style of writing and revision works best for you?

MP: Because I can’t keep anything straight in my head. It’s like psychedelic Gnip-Gnop on amphetamines in there. Gotta pin it down in a physical sense.

MG: You mention your daughters in some of your work—what influence has being a father had on your writing?

MP: Superficially speaking, it has given me loads of new material. But more to the point, my children help me focus less on being the man I think I am and more on the man I oughta be.

MG: What’s the worst interview question anyone’s ever asked you?

MP: All interview questions are perfectly lovely because like a politician I can turn them right around and try to sell you a book.

MG: Where is the best place to write in Wisconsin?

MP: Anyplace with coffee and insulation.

MG: What’s next for you?

MP: Right this second? Gotta go to my fire department meeting and learn about this new CPR.

**

Michael Perry is a New York Times bestselling author, humorist and radio show host. Perry’s memoirs include Population 485, Truck: A Love Story, Coop, and Visiting Tom. Raised on a small Midwestern dairy farm, Perry put himself through nursing school while working on a ranch in Wyoming, then wound up writing by happy accident. He lives with his wife and two daughters in rural Wisconsin, where he serves on the local volunteer fire and rescue service and is an amateur pig farmer. He host the nationally-syndicated “Tent Show Radio,” performs widely as a humorist, and tours with his band the Long Beds (currently recording their third album for Amble Down Records). He has recorded three live humor albums including Never Stand Behind A Sneezing Cow and The Clodhopper Monologues, is currently finishing his first young adult novel, and can be found online at www.sneezingcow.com.