Interview: Douglas Trevor

Midwestern Gothic staffer Kelly Nhan talked with author Douglas Trevor about being a scholar of British literature, literary communities, his interest in the Industrial Midwest, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Kelly Nhan talked with author Douglas Trevor about being a scholar of British literature, literary communities, his interest in the Industrial Midwest, and more.

**

Midwestern Gothic: What is your connection to the Midwest?

Douglas Trevor: I moved from Boston to Iowa City in 1999 and I have lived in the Midwest ever since, moving to Ann Arbor from Iowa City in 2007. So my connection was initially through work. But now I have two kids who were both born in the Midwest, and an English Bulldog from outside Pontiac, so I feel pretty tethered to this part of the country.

MG: You previously worked as an editor for The Iowa Review. Does your experience reading other’s work influence the process of writing and submitting, or publishing your own?

DT: Editing a journal is very hard work. I was the fiction editor at The Iowa Review for four years. I stepped back from the job because I thought it made writing harder. Not simply because there were several hours a day that I had to spend reading submissions, but also because I felt my own narrative voice clouded over at times by what I was reading. It’s one thing to have Alice Munro in your head; that’s instructive, But when I was combing through hundreds of stories, many of which hadn’t been fretted over enough before being sent off, it made it harder for me to nestle into my own fictive world. I still miss many things—discussing submissions with the staff, reaching out to writers and publishing their work, seeing them win awards, and so on. And I definitely learned the importance of submitting my own work when I was sure it was done, as opposed to when I wanted to publish something. But I think being an editor and a writer is a tall order, at least for me.

MG: As a scholar of early modern British literature and a writer of contemporary literary fiction, do you find that the two connect or influence each other?

DT: I think the definitely do in my case. I’ve been writing more in recent years about academics and academic culture, largely from a comic point of view, so that’s afforded me an opportunity to write about—for example—a scholar who finds a long-lost Shakespearean couplet in my story “Sonnet 126” (this was in the fall 2013 issue of the Michigan Quarterly Review) or an academic who ends up running a fake lecture series and having a mid-life crisis (this story, “The Program in Profound Thought,” came out in the Notre Dame Review in July of this year). I think about Renaissance writers all of the time when I’m working—particularly Shakespeare and the way he develops characters and crafts scenes in which we learn about these characters in dramatic ways. And I think a lot about John Donne, probably my favorite writer, because like me he was torn between writing creatively and also trying to produce “serious” academic prose.

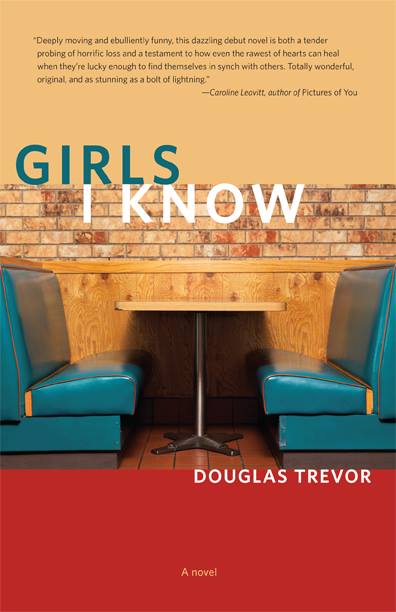

MG: Your novel, Girls I Know, deals with how three characters from separate racial/ethnic/class/experiential spheres deal with trauma and grief. Similarly, your first published work, The Thin Tear in the Fabric of Space, takes up loss as a center point across its constituent short stories. What do you think the role of writing is in dealing with or confronting pain?

MG: Your novel, Girls I Know, deals with how three characters from separate racial/ethnic/class/experiential spheres deal with trauma and grief. Similarly, your first published work, The Thin Tear in the Fabric of Space, takes up loss as a center point across its constituent short stories. What do you think the role of writing is in dealing with or confronting pain?

DT: I think Randall Jarrell put it well in his poem “90 North”: “Pain comes from the darkness / And we call it wisdom. It is pain.” That is, I don’t take as a given that my characters will learn necessarily from their experiences of loss; up to now, at least in print, I have been largely interested in what it means to try to grapple from loss. The origins of this interest are pretty straightforward in my case. My sister Jolee died unexpectedly of an aneurysm when I was 29 (she was 32). Jolee had a seventh-month-old baby at the time. That year, and the years that followed immediately, were—to say the least—very hard on me and my parents. I was consciously writing about Jolee’s death in Thin Tear, and perhaps less consciously so in Girls I Know. So I guess pain and loss is a natural site from which creative expression springs, but it isn’t the only site. The stories I’m working on now are not fixated on loss and grief. Some of them are more overtly humorous; others are thinking more directly about what is happening in our country at this time, although I wouldn’t call them political per se.

MG: You recently did a reading at Nicola’s Books in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Do you find that there is a still a kind of literary community, or pockets of literary communities, despite certain changes in how books are published, distributed, and read (namely, the internet)?

DT: Oh, without question. Nicola and Lynn (the event planner at Nicola’s Books) have been unbelievably generous toward me and my work. Getting to know them, and other booksellers in the US, is absolutely one of the greatest joys of being a writer. I grew up in Denver, home of the Tattered Cover Bookstore, and one of the booksellers there, Laura, has been working at the store since I was a kid. She introduced me when I read from Girls I Know last summer. So there is a literary community, quite tightly knit, in the US, but it is under attack and I worry about this—particularly how we don’t know what we have lost until we have lost it. I worry about this with regards to gentrification in cities like San Francisco, where artists and writers and low- and middle-income families are being pushed out of the city. And I worry about this with regards to Detroit, and how the rebirth of that city could leave certain neighborhoods behind. These are all connected issues and have to do with the kind of country we want to have and/or are willing to accept. I am thrilled when readers encounter my work online, but not everyone has a laptop, so I care—as a writer—as much about libraries as I do brick-and-mortar bookstores, although I care a lot about the latter, obviously.

MG: Girls I Know is set in Boston, and has been described by critics as a “love song” to the city. What was your research process prior to or while writing?

DT: The research was kind of endless. First, I lived in Boston for six years and by about year three I was determined to write about the place. Then I learned of a restaurant shooting that had occurred in Chinatown and decided to base a novel on the aftermath of a similar, now fictive shooting I set in Jamaica Plain. I wanted my different characters to come from different parts of the city, so I started to research different neighborhoods. As much as possible, I walked around the city. But at a certain point in the writing process, I found, I had to leave this kind of work behind and just trust the experiences my characters were having. So that’s what I tried to do.

MG: How was the Midwest influenced your writing?

DT: I have been writing increasingly about the Midwest in recent years. The story I mentioned above, “The Program in Profound Thought,” is set in Iowa City, and I have a couple of stories in my next collection that are set in Ann Arbor and Detroit respectively. I’m particularly interested in the Industrial Midwest—what it means for this region of the country to try to reinvent itself and how this reinvention affects its inhabitants. Coming from Iowa, Michigan is a very interesting Midwestern state; some of the urban spaces here remind me of the Northeast, and I think the juxtaposition/tension between rural/suburban and urban in Michigan is something I’ve recently found myself really interested in exploring as a writer.

MG: What’s next for you?

DT: I’m putting the finishing touches on my next collection of stories this summer, then tackling my next novel (about growing up in Denver) this fall. And I have to get my Shakespeare course ready to roll for September.

**

Douglas Trevor is the author of the short story collection The Thin Tear in the Fabric of Space, which won the 2005 Iowa Short Fiction Award and was a finalist for the 2006 Hemingway Foundation/PEN Award for first fiction. His first novel, Girls I Know, was the recipient of the 2013 Balcones Fiction Prize. Trevor’s work has appeared in The Minnesota Review, New Letters, The Paris Review, Glimmer Train, Epoch, Black Warrior Review, The New England Review, Michigan Quarterly Review, and more than a dozen other publications. He also has work forthcoming in The Iowa Review. Two of Trevor’s stories have been nominated for Pushcarts; others have been anthologized in The O. Henry Prize Stories and The Best American Nonrequired Reading. Currently he teaches in the University of Michigan’s MFA Program as an associate professor.

July 29th, 2014 at 9:01 am

[…] just did an interview with Kelly Nhan at Midwestern Gothic. You can read it here. Kelly is one of our more remarkable University of Michigan undergraduates. Midwestern Gothic is […]