Interview: Justin Hamm

Midwestern Gothic staffer Kelly Nhan talked with author and poet Justin Hamm about embracing the Midwest, crumbling small towns, the museum of americana, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Kelly Nhan talked with author and poet Justin Hamm about embracing the Midwest, crumbling small towns, the museum of americana, and more.

**

Kelly Nhan: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Justin Hamm: I’ve lived in Illinois and Missouri my entire life. When I was younger I thought a lot about other places I might move when I got older. I decided I’d stay put if I could catch for the Cubs. Otherwise, I figured I would be a writer for Weekly World News. I’d travel around the country looking for bizarre stories, Bigfoot sightings, that sort of thing (this was before it occurred to me that Batboy was probably just made up in somebody’s basement). This was my version of the run-away-and-join-the-circus dream.

But I stayed. Studied, married, moved states from Illinois to Missouri. And at some point, maybe six or seven years ago, I started to become deeply interested in the region, in its particular people and stories. Within a short time I got married, lost my mom, and became an adult, and I guess in the madness of all that change, I wanted to grab onto something that rooted me. The intensity of the seasons felt important, and the way the fields look different here depending on the month—every small thing I’d taken for granted growing up suddenly mattered. I felt like I’d uncovered a connection that had always been there but that I’d maybe been too immature to see. It was an important moment for me as a writer, certainly, but even more so as a person.

KN: How has the region influenced your writing?

JH: Embracing it has been one of the most important steps in my growth. Place always attracted me, as long as it was someplace other than here. Early on it was Frost’s New England. Later, I worshipped Southern writers and, to an extent, Western writers. Larry Brown, Barry Hannah, Rick Bass, and Cormac McCarthy—I wrote mostly fiction, trying to channel them when I wrote, and I cultivated a flashy, ultra-masculine gimmick of a voice.

But whatever was real and authentic at the heart of these writers, I didn’t have anything like that. All my examples at the time were Southern; I didn’t know any writers who could show me how Illinois might sustain literature the way, let’s say, Mississippi could. Finally, without any expectation of publication, or really any plans to even show them to other people, I started writing poems to work through the hard period I mentioned above. There was no workshop deadline, no pressure to impress anyone, and I wound up writing plenty of impressively awful stuff, but also some of the first poems that I think sound like me. Many of those better poems dealt in some way with Illinois, and later, Missouri.

Jason Jordan, who edits decomP, read my first chapbook a couple of years ago, and I don’t remember the exact quote, but he said something to the effect that he equated my poems with being raw and authentic. I’ve never received a compliment that moved me more.

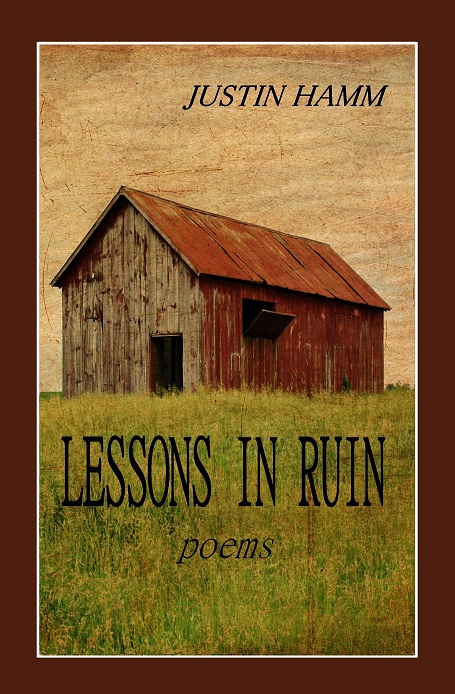

KN: What can you tell us about your upcoming poetry collection, Lessons in Ruin?

KN: What can you tell us about your upcoming poetry collection, Lessons in Ruin?

JH: Naturally, I’m excited about getting it out there, and I’m making sure I enjoy the whole process of publication. I never took for granted I’d get this opportunity, and I don’t take for granted that I’ll get it again. The book will be available at Amazon and from select bookstores September 1st and can be pre-ordered from my website justinhamm.net right now.

The poems are mostly narrative, sometimes gritty and sometimes funny (I hope). They’re about Illinois and Missouri and social class and memory and speaking in tongues and death and rust and vengeful birds and accordionists and baseball. Oh, and most of all, they’re about relationships—to home, to parents, to children, to partners, and to friends.

At one level the title offers a way the poems might fit together. They are nearly all in some way or another about this idea of ruin: the physical ruins of place; the emotional ruins of people; or else ruin as a verb, meaning the ways we participate in damaging others, ourselves, or situations. There’s also a strain of a story running through all of them. I hope it is a book that works as a whole as well as at the poem level because I put a lot of work into assembling it with that in mind.

KN: From having read some pieces from the collection, we noticed that you evoke these images of deterioration, of “ruin”, and even include specific names of the people from these scenes. Where do these images come from? And is there hope amidst that ruin?

JH: I’m in the car and moving through the landscape around here a lot. So the inspiration for these images comes from what I see, what moves me: the collapsing barns and abandoned farmhouses and rusted out old cars I pass on my morning commute through rural Missouri, the crumbling small towns with their empty Main Street storefronts dotting the route back home to Illinois, and the forgotten factories here in the town where I live today. They come out of language, too—often, following the language results in images I didn’t expect.

The people are composites, drawn from my own experiences growing up in a blue-collar family along with what I continue to pick up in the course of daily life. Around here—and really anywhere, I guess—you don’t have to look hard to find people who are up against it. Sometimes the people come partly or even purely from the imagination, too. It can be hard to separate out exactly how much of each influence goes into making them. I worry less about that and more about whether they’re honest depictions.

Despite the ruin, and despite the hard luck, there’s definitely still humor and perseverance and tenderness and hope in the collection. Again, honesty demands that. And so you have the humanity of the accordionist who plays to comfort the widow, for instance. The tenderness of the father who wakes early to make pancakes for his daughter. The curious compassion of the small boy who wants to understand his grandfather’s pain at having to sell off the family farm. The awe the husband feels at the woman his wife has grown into during their time together. Or the independent spirit of the mechanic who understands that sometimes he must blow off work and let his daughter blow off school so they can fix the car together and people-watch all day.

KN: What inspired the goal behind your literary journal, the museum of americana and its stated interest in reviving pieces of American obsolescence?

JH: Really it started with my fascination with history in general and Americana in particular. It’s so rich and strange that I hate to think any of it might be forgotten (or worse, scrubbed away by those who refuse to acknowledge it). But at the same time, I didn’t want to be another Antiques Roadshow or American Pickers either. At least not exclusively. I love what those shows do, but I thought what would keep the literature vital would be to try to do something new or interesting with the artifacts it chooses to uncover.

At one point early on in writing the poems that would eventually become Lessons in Ruin, I thought what I was writing toward would be a sort of grab bag that used Americana as raw material for something new. I quickly found out that I wasn’t ready to make what I saw in my head come out on the page. It was too big of an idea at the time. But I thought a whole group of people contributing their particular interests in Americana could come together to make something like what I envisioned. And it has gone far beyond that.

KN: Does working as an editor for a literary journal and reading other people’s work influence your own writing?

JH: From a craft perspective, it doesn’t have that much influence. We have an incredible editorial team, and I try to stay out of their way until we get closer to production. So my role has more to do with coordinating our general vision and then coming in to talk about final decisions. What this means is I’m lucky enough to read mainly the best of what we’re sent. I’ve heard other editors say they learn a lot about what not to do from reading submissions; because of the nature of what I read, I learn more about what possibilities exist, and also about how others interpret a vision that started with one of my own failed projects. It’s inspiring. Constantly reading good work from writers I don’t know makes me want to join the conversation.

KN: Who are some of your favorite Midwestern writers?

JH: There are so many great ones connected to the region in one way or another. Cornelius Eady is a favorite. I also love Jim Harrison and Norbert Krapf, William Trowbridge, Dan Chaon and George Bilgere. Sandy Longhorn’s Blood Almanac and Michael Walsh’s The Dirt Riddles are two Midwestern poetry collections that have meant a lot to me. And Cindy Hunter Morgan is a name to pay attention to—both of her chapbooks are excellent and she’s working on a full-length collection right now. I’m lucky enough call fiction writer Chad Simpson and poet Michael Meyerhofer my friends, and both are immensely talented. I also love classic literature, probably more than I’m supposed to if I want to be hip and contemporary. So Illinois poets Sandburg and Masters are major figures to me. And I can’t leave out Chuck Berry or Bob Dylan. They’re giants.

What’s next for you?

Good question. Lessons in Ruin has provided basic direction for about six years. Even now, I’m writing new poems that seem to belong to that project. I’m not going to stop writing them if they come.

But at the same time, I’ve been working on other things in small bursts along the way. I have a handful of poems rooted in English folk music and fairy tales and I want to get back to exploring those. And I have a chapbook length collection of flash fiction/short stories that are after the spirit of those Weekly World News articles I loved as a kid. I’ve been publishing them individually for a couple of years and hope to eventually see them published together, if they’re good enough.

Lessons in Ruin came out of a process, and it will be interesting to see if it holds up when the next idea strikes. I kept a very general theme or connection in mind, but under the umbrella of that connection, I let the poems figure themselves out and do whatever they seemed to want to do. I tried to be as open as possible to anything that might suggest itself, trusting my own obsessions as a writer or poet would create the cohesion I needed. Later, when I had a lot of poems, I began to carve the book out. I felt like I was sculpting it rather than building it. That’s why it’s hard for me to imagine what the next larger project might look like. If the process holds, I probably won’t know until I’m most of the way there what it really wants to be.

Lessons in Ruin is available for pre-order at justinhamm.net.

**

Justin Hamm is the author of a full-length collection of poems, Lessons in Ruin, and two poetry chapbooks. He is also the founding editor of the museum of americana. His poems or stories have appeared in Nimrod, Cream City Review, Punchnel’s, Hobart, Quiddity, and the Bob Dylan-themed anthology The Captain’s Tower. Recent work was also awarded the Stanley Hanks Memorial Poetry Prize. His website is justinhamm.net.