Interview: Peter Grandbois

Midwestern Gothic staffer Stephanie Mezzanatto talked with author Peter Grandbois about Ray Bradbury, his Midwest sensibility, the influence his students have on his writing, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Stephanie Mezzanatto talked with author Peter Grandbois about Ray Bradbury, his Midwest sensibility, the influence his students have on his writing, and more.

**

Stephanie Mezzanatto: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Peter Grandbois: I was born in Minnesota but grew up in Colorado. I came back to the Midwest as an adult where I lived and taught in Chicago for many years in the 90’s. Then, moved away again, only to return most recently to Ohio where I’ve lived the last five years. So, the Midwest has been a presence weaving through my life since the beginning.

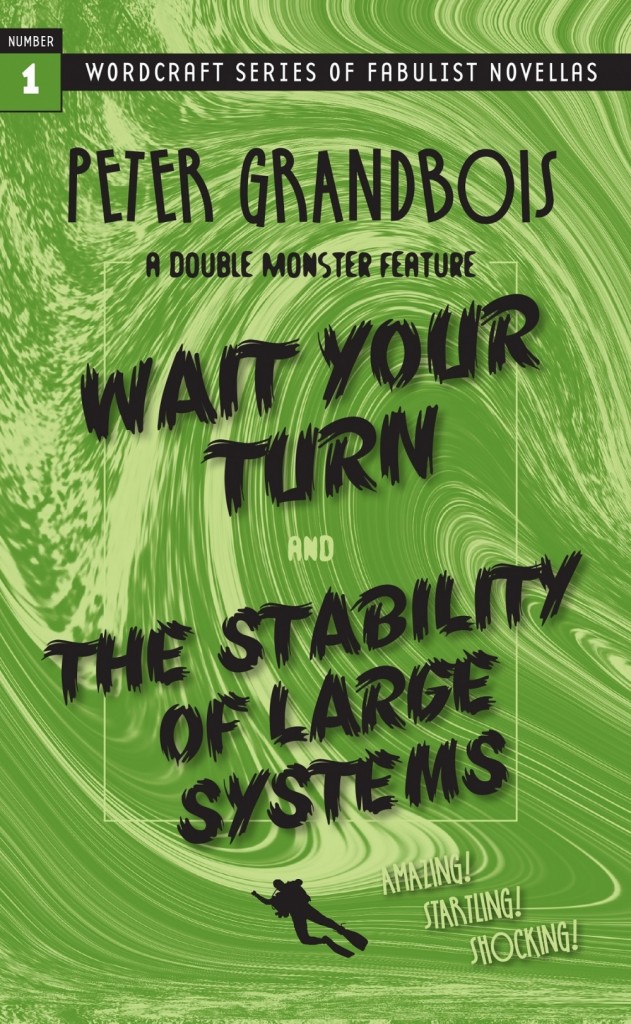

SM: In your novella double feature, Wait Your Turn and The Stability of Large Systems, you play with the intersection of fiction and reality, treating the characters in your novellas as real, yet heavily connected to their fictional cinema selves in in The Creature from the Black Lagoon and The Fly What inspired your idea to bring a more honest, believable side to the unrealistic characters in these films?

PG: I wasn’t necessarily thinking in terms of bringing a more “honest, believable side” to the monsters in the films but actually the reverse, bringing a more honest, believable side to the humans that live in our “real” world. The image that inspired my first thoughts about these monster novellas came years ago when I was walking through a neighborhood and saw a birthday party in progress where various five year old boys were bouncing on a trampoline. One of the father’s suddenly started yelling at his boy to get down and yanked him off the trampoline. It wasn’t overtly violent, but it was violent. And it got me thinking about the times I’d crossed the line myself, either with my children or with others. I thought about the monster that lurks in all of us and how little we like to talk about our more violent impulses. So, the goal in these novellas was to explore the monstrous within the human as much as it was to explore the human in the monster.

SM: Stephen Graham Jones called the monsters (The Creature and The Fly) in Wait Your Turn and The Stability of Large Systems “painfully wonderfully human.” When you were writing your novellas, was it your intention for the development of these characters to speak to the primitive components of human nature?

PG: The short answer, as I hint at in the above question is yes. I was very much looking to explore those primitive components of human nature. But my point was to show that these components aren’t so “primitive” at all. We like to think they are “primitive,” but in fact the 20th century was the most violent century in the history of humanity. We are, if anything, getting more violent as we get more “civilized.” We simply hide it better. I actually see this as a very Midwestern theme because on the one hand Midwesterners are some of the nicest people you’ll ever meet and on the other they often are very proud of their guns. Three of these monster novellas are set in small towns in the Midwest but in all of them the “monster,” whether the Creature from the Black Lagoon, or The Thing, or The Blob, is the guy next door. He is not that different from you and me. His life has gotten a little messy is all, and like the rest of us, he is trying to find his way out of that mess. The fear of that mess, the fear of the fact that life can become messy, is what makes him a monster. What makes us all monsters is when we act as a result of that fear.

PG: The short answer, as I hint at in the above question is yes. I was very much looking to explore those primitive components of human nature. But my point was to show that these components aren’t so “primitive” at all. We like to think they are “primitive,” but in fact the 20th century was the most violent century in the history of humanity. We are, if anything, getting more violent as we get more “civilized.” We simply hide it better. I actually see this as a very Midwestern theme because on the one hand Midwesterners are some of the nicest people you’ll ever meet and on the other they often are very proud of their guns. Three of these monster novellas are set in small towns in the Midwest but in all of them the “monster,” whether the Creature from the Black Lagoon, or The Thing, or The Blob, is the guy next door. He is not that different from you and me. His life has gotten a little messy is all, and like the rest of us, he is trying to find his way out of that mess. The fear of that mess, the fear of the fact that life can become messy, is what makes him a monster. What makes us all monsters is when we act as a result of that fear.

SM: You were born in Minnesota, then made your way to the West, then the East, and finally came back to the Midwest. What aspects of the Midwest did you bring into your writing while writing in the West and the East? How do you think your identity as a Midwesterner has influenced your writing?

PG: That’s a really great question. The old adage is you can take the boy out of the country but you can’t take the country out of the boy. Though most of my life has been spent in the west, I very much believe my sensibility is Midwestern, and it all goes back to those days in my youth sitting around with relatives on the farm in Wisconsin or around my grandparents house in Minneapolis for holidays or family get-togethers. My first novel, The Gravedigger, is set in Spain in the 1920’s, but the truth is it is a Spain filtered through my own Midwestern sensibilities. The earthy humor. The heart. The laughter in the face of great sadness. All that comes from my Midwestern upbringing. The same thing for my second novel, Nahoonkara, which takes place in both Wisconsin and Colorado. The characters are absolutely Midwesterners. They are the manifestation of my childhood memory of my relatives. And as I mentioned above, three of these new monster novellas are set in small towns in the Midwest—Ohio to be exact. That small town, Midwestern setting seemed essential to the “everyman,” or rather “every monster” theme that underlies those books. I have a third novel, as yet unpublished, that follows the Ojibwe in the 1800’s and takes place entirely in Minnesota. I hadn’t realized until now how deeply I am a Midwestern writer.

SM: As a teacher of creative writing and contemporary literature at Denison University, how has the work of your students influenced your own writing?

PG: I dedicated my story collection, Domestic Disturbances, to my students as a way of acknowledging the deep debt I feel toward the influence my students have on my own writing. It is one of the great joys of being a teacher to share this enterprise of attempting to create something from nothing with students. It is daunting. There is nothing more frightening in my mind than facing the blank page, and yet my students sign up for my classes where they have to do exactly that. I draw inspiration from their courage, from their willingness to take risks, from their honesty, and, very often, I am inspired by something they’ve written. I see the role of teacher as being more than simply a lecturer, more than simply even a facilitator—whatever that is—but rather as someone who invites students to be part of the creative conversation. We converse. I share my ideas. They share their ideas. And through that process we help each other to the other side of that blank page.

SM: Which authors have had the greatest influence on your own style? Do you remember the first author or book that inspired you to write?

PG: Yes, My first, deepest influence is Ray Bradbury—a Midwestern writer, and a writer for whom most of his stories are set in the Midwest. I don’t read him much any more, but those writers we read when we are young have a tremendous impact. As an adult, the first huge influence on my writing came when I discovered the Latin American magic realists: Borges, Cortázar, García Márquez, José Donoso, and Juan Rulfo. Rulfo’s Pedro Paramo was a huge influence on me as it was on García Márquez himself. Interesting, Rulfo is a Mexican writer, writing about a small town in Mexico, and yet many of his themes could easily be seen as Midwestern. I’m also very much into European and Asian literature. The Portuguese writer, José Saramago, is a big influence, as is the Spanish writer, Javier Marias. With Japanese writers, I could go on and on, starting with Kobo Abe and ending of course with Murakami. Of the Americans, Steven Millhauser’s work is hugely important to me, and like Bradbury, he’s someone who writes about the fabulous and strange in small town American life, even if his towns are often set in the east.

SM: What advice would you give to new writers that you wish you had known when you first began writing?

PG: That’s a great question because it keeps me from saying the usual answer, which is to “read, read, read” because I knew that already when I first started writing. What I didn’t realize, and what I wish someone would have said—though I probably wouldn’t have listened—is to remember that there is no rush. There’s so much pressure now to get your work out into the world, to publish so you can get into grad school, to publish so you can get a job, etc. I think that’s created a tendency to flood the market with a whole lot of work that isn’t as good as it could be. I work as senior editor for Boulevard, one of the top literary magazine’s in this country, and, I should say, one of the most important Midwestern magazines, as it’s based in St. Louis. In my work as an editor, I see lots and lots of good stories that don’t quite make it because the writer didn’t take enough time to make it a great story, i.e. to make it work on every level: language, character, subtext, etc. Writers settle for finding a cool voice or an interesting idea and think that’s enough to make a great story, and it isn’t. So, I would say, slow down. You’re building a model ship. Take your time. Make sure each piece is in place. I know this is easier said than done, especially coming from someone who is now on the other side with a tenured position, but slow down. It’s about the work. Making it as good as it can be. Listening to it even when you thought you were done listening to it. There are few things in this world that mean a lot. Capitalism has demeaned so much of our humanity. Great writing still means everything. At least to me. It’s not about writing a million copy best seller. It’s about saying something true and saying it well. It’s about reaching just one reader. To do that, you’ve got to slow down.

SM: What’s next for you?

PG: Poetry. For some reason I can’t quite account for I started writing poetry recently. Some people who know me say that it makes a strange sort of sense, that my fiction has been veering toward poetry for a long time now, but all I can say is that I was in the middle of working on a story, a fabulist piece about a woman with a stalagmite growing out of her mouth, when I put the story down and said I’m going to write poetry for awhile. I’ve written thirty poems so far and see no sign of stopping yet. The interesting thing is that the poems are so clearly Midwestern in terms of language and theme. I’m suddenly finding myself using images of the Midwestern landscape over and over, as if there was a nature poet in me all along fighting to get out. I don’t know where it will lead, but I’m willing to follow this poet who has emerged for as long as he’ll let me.

**

Peter Grandbois is the author of seven previous books including, most recently, The Girl on the Swing (Wordcraft of Oregon 2015). His work has previously appeared in such journals as The Kenyon Review, Boulevard, The Denver Quarterly, New Orleans Review, Eleven Eleven, Zone 3, and Failbetter, among many others, and has been shortlisted for both Best American Essays and the Pushcart Prize. His plays have been performed in St. Louis, Columbus, Los Angeles, and New York. He is senior editor atBoulevard magazine and teaches at Denison University in Ohio.