Interview: Theodore Wheeler

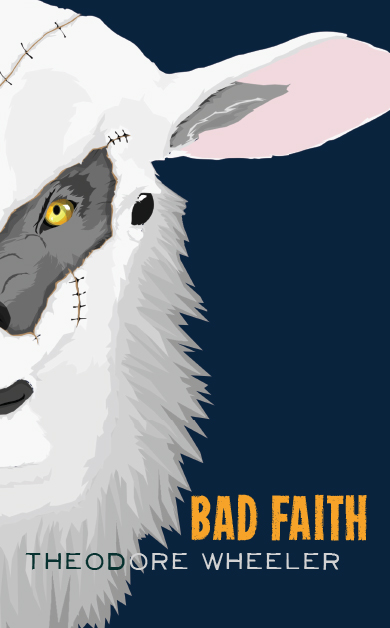

Midwestern Gothic staffer Allison Reck talked with author Theodore Wheeler about his collection Bad Faith, writing from different points of view, the vulnerability featured in his stories, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Allison Reck talked with author Theodore Wheeler about his collection Bad Faith, writing from different points of view, the vulnerability featured in his stories, and more.

**

Allison Reck: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Theodore Wheeler: I was born in Council Bluffs, Iowa, and have lived in the Midwest my entire life. I also enjoy eating dinner early on the weekends and experiencing all four meteorological seasons. So, solidly Midwestern.

AR: You were a fellow at the Akademie Schloss Solitude in Germany in 2014, but you live in Omaha, Nebraska. Do you think that living in such different environments influenced your writing in some way?

TW: The two places seem pretty similar to me, besides some terrain and weather differences. I imagine that this is mostly due to the fact that the whole time I was in Stuttgart I was working on a novel that’s set in Omaha (mostly), Chicago, and Wisconsin. So even while I was there, Omaha never really left me.

Probably the biggest difference was the language barrier, as I don’t speak German. Even though a lot of Germans do speak English and it’s pretty easy to get by without much German, the experience of living at least partially outside my language was great, and is something I really miss. I think the pace of my sentences are different as a result — that I simplified things a lot, with shorter and halting sentences that build into something more complex and exciting, because of the way I was communicating there.

AR: Your new collection of stories, Bad Faith, includes a diverse group of subjects – from a boy with a disabled father to a biracial man at his white mother’s funeral. How did you manage to write from such different points of view in your stories? Did you notice your writing style changed with each different perspective?

TW: There is some change in style, of course, depending on how close the POV is to the main character and what I’m trying to do with the story. I write around a story a lot during early drafts — doing side histories, biographies, exploring setting — mostly with the idea of finding the voice of the story. Sometimes that voice is very close to a character’s, sometimes not. Part of the appeal of writing fiction is speculating what it’s like to be someone who’s very different. I’m not biracial, I don’t have a disabled father, both my parents are alive. If the story is successful, a great amount of empathy and imagination is necessary, and I hope my writing rises to that occasion. Finding common ground, discovering things about different people–that’s exciting stuff!

AR: In addition to writing, you work as a legal reporter for the civil courts of Nebraska – a dramatic departure from fiction writing. How do you cope with the change between writing styles and subject matter? Are there any specific tricks you use in your craft process to redirect your writing to an opposing genre?

TW: I’m not sure that there’s any trick to it. Switching between fiction and reporting hasn’t really been a problem for me. If you look at writing as performance, it’s about engaging the character, the voice that’s required for the task at hand. That sounds utilitarian, and I guess it is. Probably one thing is that I don’t really think about it that much. Also, I almost always take a 15-20 minute nap or go for a walk after writing fiction and before starting my day job. That probably helps switching gears more than anything.

AR: Bad Faith is described as a collection in which “the herd can’t always outpace the predator.” What exactly does this mean to you, in relation to the theme of fleeing or rejecting a contemporary domestic life?

TW: That life is overwhelming a lot of times, particularly in small moments of crisis that short fiction examines. Most of the characters in the book really do try to do right by the people in their lives, but that also makes them vulnerable. Like a straggler too far away from the herd is vulnerable, more or less.

AR: In addition to your newest collection, Bad Faith, you have previously published a chapbook and multiple stories in other literary journals. Now, you also have a novel, Kings of Broken Things, forthcoming in 2017. What do you feel are the advantages (or disadvantages) of having made your debut in short form fiction rather than publishing a novel at the start?

TW: It isn’t this way for everyone, obviously, but I feel like this is the more traditional path for writers, proving their mettle through progressively bigger publications, learning more about the art and business sides and being able to pull off bigger projects. Having the chapbook come out last year allowed me to learn the basics of how to promote a book — things like how to contact booksellers, how to put together a launch party, what kinds of things resonate in a PR pitch — while not really having to worry about sales so much. Nobody’s livelihood was depending on my chapbook sales. That being said, we went through two printings of On the River, Down Where They Found Willy Brown, which felt like a nice victory.

As to having the collection or novel come out first, I feel like it’s pretty similar along these lines. Certainly publishing a book is a big investment for any publisher and I’m grateful for all the time, effort, sweat, and tears Queen’s Ferry Press has put into getting Bad Faith out there. There was a publicist who booked readings, experienced book pros who put it together. But, still, a small operation. Having my novel published with a New York house seems like a different kind of experience, and one I’m enjoying so far.

AR: In the advanced praise for Bad Faith, fellow authors hailed you for your “nuanced understanding of human nature” and said that your stories revealed the “malice, confusion, and ultimate frailty of us all.” Do you agree with this commentary, that your collection exposes humanity as confused, malicious and frail? What did you hope to convey about humanity in writing these stories?

TW: I didn’t really intend to write a mean-spirited book, and I don’t think it is. There’s something really compelling to me about vulnerability, particular those who are willfully exposed and those who try to cover up weakness by being cruel to others. There are a few malicious characters in Bad Faith — notably Aaron Kleinhardt, a criminal element who appears in two stories and seven between-story vignettes — but for the most part these are people who are vulnerable and different, but not really that interested in covering up their frailty.

AR: What’s next for you?

TW: I’m really excited for the release of my debut novel next summer, Kings of Broken Things. It’s set during World War I in Omaha and follows two young immigrants who become mixed up with different elements involved in the Omaha Race Riot of 1919 and the lynching of Will Brown. Hopefully it’s a novel that’s timely and timeless, as the cliché goes. I can’t wait to share it with readers.

Right now I’m working on another novel, tentatively titled From the Files of the Chief Inspector, that features stories of love lost and abandoned set in the context of a post-9/11 domestic spying campaign. It’s coming along.

**

Theodore Wheeler is the author of Bad Faith, a recently-published collection of short fiction, and Kings of Broken Things, a novel that’s forthcoming in 2017. He’s been published in Best New American Voices, New Stories from the Midwest, The Southern Review, The Kenyon Review, and Boulevard, among others, and his story “The Mercy Killing of Harry Kleinhardt” appeared in Midwestern Gothic Issue 8. He lives in Omaha with his wife and two daughters.