Interview: Jay Baron Nicorvo

Midwestern Gothic staffer Kathleen Janescheck talked with author Jay Baron Nicorvo about his novel The Standard Grand, raising chickens, writing his way to the surface, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Kathleen Janescheck talked with author Jay Baron Nicorvo about his novel The Standard Grand, raising chickens, writing his way to the surface, and more.

Jay will be appearing in Michigan to promote his book next week and the week after! Stop by the following locations to hear him talk about The Standard Grand:

April 26th, Wednesday 7:00 PM at Bookbug in Kalamazoo, MI (details)

May 3rd, Wednesday 7:00 PM at Literati in Ann Arbor, MI (details)

**

Kathleen Janescheck: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Jay Baron Nicorvo: For a few of my earliest years, my family lived in a Chicago suburb while my parents’ marriage collapsed. They’d been together for more than a decade, right out of high school, when they decided to have kids — I’m the oldest of three boys, the Dmitri, you might say, if you’re a Brothers Karamazov fan — as a way to maybe salvage their relationship, or to distract themselves from it. No such luck.

I still have stark memories of my earliest Illinois days: harvesting red clay in the surrounding undeveloped lots; the collective fear of a confirmed child molester trolling through the neighborhood in an old orange Volkswagen, soliciting kids; coming home from an outing with the family next door to find my mom, eight-and-half-months pregnant, unconscious on the floor of her bedroom, phone off the hook beside her. (I’m realizing my father’s in none of these recollections.) I don’t think these experiences are particularly Midwestern; they’re more typically suburban American.

After my youngest brother arrived, my mom moved us back to the Jersey shore, where I’d been born. My mom’s as “Jersey Girl” as they come — the song not the movie, and more the original, raggedy-ass Tom Waits version than the smoldering Bruce Springsteen rendition. Five years later, when she got sick of Jersey once and for all — sick, really, of the gray, rainy winters cooped in a duplex with three feral boys — she and her sister relocated us to Florida so we could run wild in the temperate December sun. I spent the next twenty-five years shuttling up and down the Gulf and East coasts — Sarasota, Boston, St. Petersburg, New York City.

My wife and I — she’s also a writer, Thisbe Nissen — bought our first house in the foothills of the Catskills of New York. Outside a little village called Saugerties a few miles from Woodstock. We lived there for a couple years and commuted insane distances for our city jobs. When we determined to have a child, our situation felt impossible. Thisbe was offered and accepted a full time teaching job at WMU in Kalamazoo, and within days, we conceived our son. After he was born, we relocated to Bedford Township, north of Battle Creek, aka Cereal City. We’ve been in Southwest Michigan for six years now. It’s not without flaw — we’re in the sticks, Trump country, woefully outnumbered and outgunned — but we love our home.

KJ: As a transplant to the region, do you think that the Midwest has seeped into your writing?

JBN: There’s a certain Midwestern sensibility to be found in my writing, to be sure, and I’m hoping that — with the publication of my first novel and the readings I’m doing in the region — some of my writing even seeps into the Midwest. They both tend toward the sincere and the heartfelt, as I understand them. They avoid irony, value intimacy and privacy. They’re hardworking; they’re earthy. There’s an unnamed tension under the surface and, oh yeah, there are guns.

Maybe it’s due to growing up poor on the East Coast and then in the South, raised by a pair of working-class Jersey girls who could both be vividly sarcastic and caustic. (I can look back, fondly, on all the times my mom told me, in all sincerity, to get bent.) But at some point in my early twenties — after my requisite snide adolescence — I became supremely earnest, and earnest I’ve remained. That strikes me as particularly Midwestern.

In person, I can’t really stomach sarcasm. Irony annoys me. I’m repelled by people who mean the opposite of what they say, even in jest. Or don’t take time to consider what they mean. I’m afraid I sound humorless, but I love humor. It’s biting wit that I don’t care for — I suppose I’m witless!

And it occurs to me that I’m really railing against everything our president represents. Trump’s just about as anti-Midwestern as they come. He’s East Coast privilege of the worst sort. Snarky. A particular brand of mean amorality. Self-serving, vindictive, materialistic, cynical and faithless. He’s a douchebag. (Can I say that in a wholesome, albeit gothic, Midwestern journal? Can you see I don’t fully belong to the Midwest?) Our menstruphobe president is a douchebag — it’s worth repeating — who gives douchebags a bad name, and the one thing I hold against Midwesterners — the knock on earnestness — is it makes you an easy mark for hucksters and conmen. A number of you — Michiganders and Ohioans especially — got conned last November, and royally.

But the thing is, when creating characters — and our president is nothing if not a character, a Dickensian Scrooge, flat to a fault — those with attitude steal the show. Same holds true for modern politics, where snark wins votes, and in reality television, where the wrecks increase ratings. In writing dialogue, like in a debate, meanness and wit score points. They create dramatic tension. The mother who shouts at her son, “Get bent!” is far more striking, and compelling, than the mother who says, “Be nice to your brothers.” But I’ve gotten distracted — what was the question again?

KJ: Though you have not personally experienced war, your novel, The Standard Grand, focuses on characters who have. What is your process for writing about things you haven’t experienced?

JBN: No, I have not experienced war, but I’ve experienced trauma and depravation. Phil Klay has a killer essay about some of the parallels. That said, my civilian traumas are not wartime traumas. The differences are exponential. And yet any hardship opens you up to empathy, and empathy, coupled with an abiding interest, can get a writer convincingly into a character. But I don’t believe I have the right to write from any point of view I choose; I believe I must earn that right every time I sit down to write.

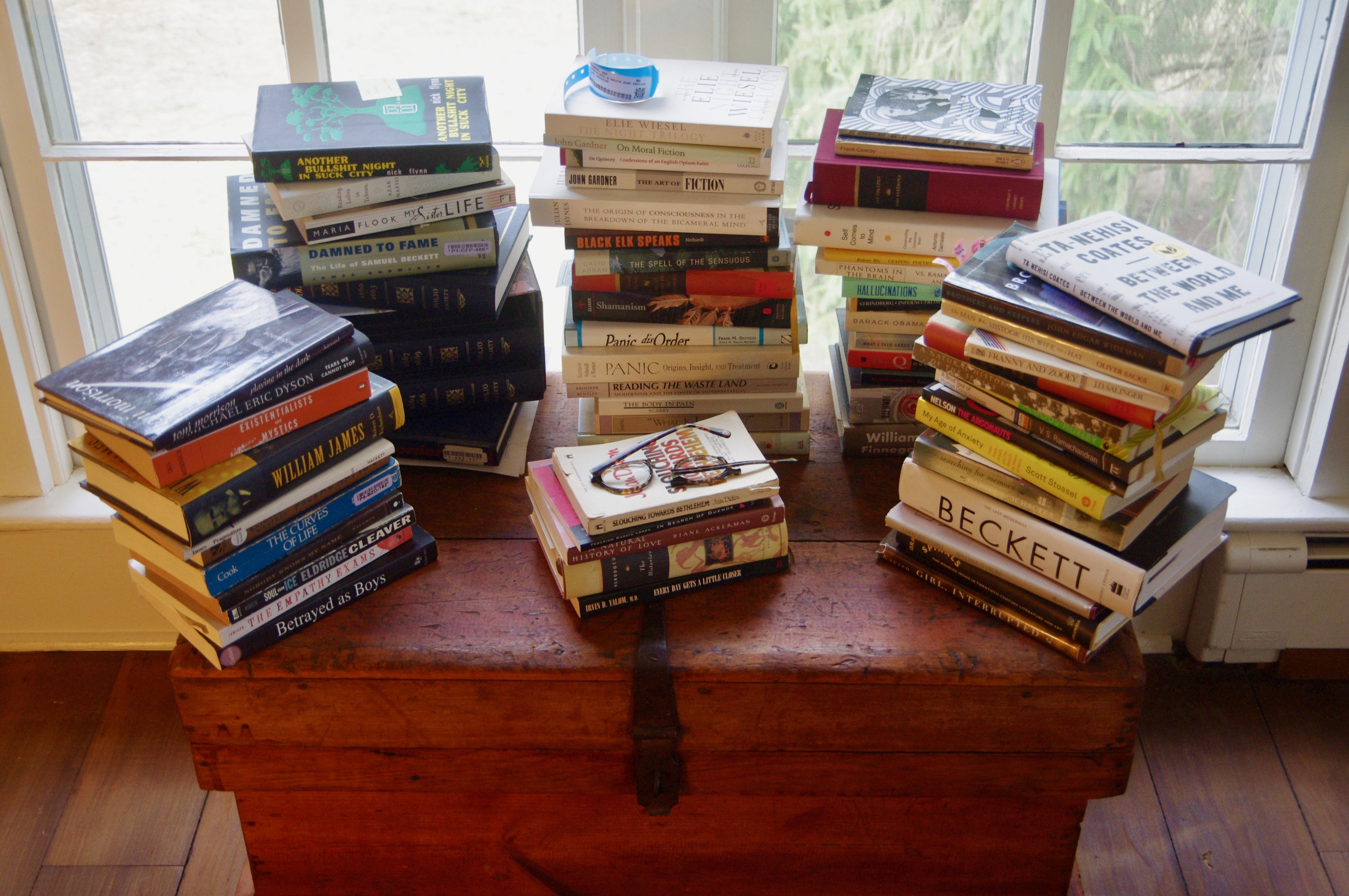

My process for this is simple if not easy: read everything. I immerse myself in a subject until I lose myself in it, literally. You’ve got to reach the saturation point where you’re drowning in primary source material. Then you write your way to the surface, and you do that partly by working hard against stereotype. Once you’ve reached the surface, once you’ve polished that surface to a shine and are reasonably sure that beneath the surface lies some significant depth, then seek out a reader who’s experienced what you’ve written about. She’ll call you on your bullshit, and you revise with her opinions in mind.

This is to say that I don’t place much stock in writers who tell you, “Write what you know.” It’s more important, and more interesting, to know what you write. It’s writing as a way to come to know something you didn’t before. I’m striving to make difference feel intimate. If I do that well, maybe I’m able to drag the reader along on a strange, new ride and, on the way, maybe some of our overlooked similarities reveal themselves. We might even end up becoming more than we were when we started out.

KJ: The main character in your novel was inspired by your former sister-in-law. How has working on this novel shaped your thoughts on her?

JBN: Outside of that initial inspiration, which I’ve written about elsewhere, it hasn’t, not really. I try to maintain separation between actual people living lives in the real world from the characters those people might inspire me to write about. There’s always a disconnect in fiction, especially, but even in nonfiction. The “mom” I’ve described above — ostensibly in a truthful way — bears little real-world resemblance to my actual mother, whose complexity, beauty, and humanity far exceed my capacities to capture her in language.

So while writing and reading about my main character taught me loads about women and soldiers, generally, Specialist Smith hasn’t taught me much specifically about my former sister-in-law. For that, I’d have to track her down and reestablish a relationship, which isn’t my place. That would be a violation of my devotion to, and my love for, my brother. Besides, both of them have moved on. They’ve both remarried. Both have children with their new spouses. My brother is far happier, and far better off, and his ex-wife appears to be, too.

KJ: Reality informs fiction. Do you ever find fiction–either writing or reading it–informing reality?

JBN: Sure, all the time, and I wouldn’t write fiction, or read fiction, if it didn’t inform reality. Our best fiction shapes our sense of reality; hell, the best fiction sometimes feels realer than reality. It helps us define and understand the world, the people, and the creatures in it. And we now know fiction, the reading of novels, offers a kind of empathy exercise. For my money, there’s no better way to inform reality.

KJ: You’ve spoken in the past about how the military dehumanizes the enemy, and in turn, leaves soldiers un-empathetic. Has this detail shaped your characterization of Specialist Antebellum Smith?

JBN: Less Specialist Smith than some of the other characters in the novel. Smith maintains a significant capacity for sympathy, and I think that’s partly her emotional undoing. The US military does an incredibly efficient job getting our soldiers ready for conflict. All attention is paid to the front end. We’ve got it down to a science. A good portion of modern combat training is Pavlovian conditioning; the world’s largest employer of psychologists is the U.S. Army Research Bureau. But we do a godawful job on the backend. We do next to no reconditioning when our soldiers come home. We’ve got to get better at re-humanizing, and my novel, in an astoundingly inefficient and obscure way, tries to offer some means that we might, as a nation, go about helping soldiers de-escalate conflict. But very specifically, and cost effectively, we can help to re-ready vets for civilian life by getting them to exercise their empathy muscles. Vets should read more novels. We all should.

KJ: Your characters are often either receiving or dispensing violence. What makes you want to write about violence?

JBN: Well here, I suppose, is one way a writer can’t escape writing what he knows. I had a violent upbringing. My mom was as loving and as affectionate as could be, but she wasn’t protective. Partly, she was parenting according to the uniformed times — more lead in the gasoline! dumb down a whole nation! to hell with the seat belts! — but mostly she was working seven days a week at a 7-11. She often wasn’t around to keep the wolves in the woods. And her second husband, come to find, was lupine, and a lunatic. But, make no mistake, I don’t want to write about violence. My writing involves the poor, and poverty — in my experience in our country in this day and age — breeds violence.

KJ: What has running a small farm taught you about writing?

JBN: Defunct farm is more like it. We grow a garden, and we have a couple dozen chickens at any one time. But we don’t run a farm; our farm was long ago overrun! I will say, though, that my most influential writing teacher, Sterling Watson, was a fan of the Southern Agrarians (sometimes called the Fugitive Agrarians), Robert Penn Warren and John Crowe Ransom among them — O, the patriarchal pretension of all the sad lettered men placing small bets on the name trifecta! — and Sterling talked often about needing to let the land lie fallow for a time after working it hard. Otherwise, you sap it of all nutrients and it won’t produce. I hold fast to that metaphor during my downtime, when I’m struggling for days to steer the walk-behind tiller, or splitting and stacking firewood for weeks, or wrestling our old tractor to a bloody-knuckle draw, or helping to raise an organic six-year-old child.

KJ: Which of your chickens is your favorite?

JBN: Good parent that I try to be, I play no favorites, but sometimes I can’t help myself. And each of our hens is her own person. They all have names, and if someone ever tells you chickens are stupid, that person’s an idiot. People are stupid. Or, people are so closed-minded and obtuse as to render themselves stupid.

To overcome our stupidity — the human bias in our pattern recognition; we can’t see the chicken for the brood — Thisbe and I won’t raise two chickens of the same breed. This way, we can tell them all apart. If you can tell them apart, you can overcome the idiocy of your prejudice. You have an easier time seeing them as individual and you’re able to observe, appreciate, and understand each chicken, who’s got her own attitude and sentience, make no mistake. This is another brand of empathy exercise. It’s also speaks to building character — both in fiction and in ourselves.

Of our newest brood, all year-old hens, there’s one who, from two-days old, was very interested and invested in us. We named her Punny Chunny Conghi, after a figurine dubbed by our son, Sonne. We kept a list of his toddler’s names for things and neologisms, and that’s one place we draw names for our chickens. There’s O’mahdee, Sonne’s mishearing of “Molly-O,” the Steve Earle song; Old Bang Bones, something Sonne called his favorite washable marker; and Huggeen, Sonne’s name for a carrot he was especially fond of.

But Punny Chun. When she was in the horse trough in the dining room with the other chicks, we’d peek our faces over the lip. She was always the first to make eye contact — usually with her left eye, which may be her dominant — and she kept that watchful orange eye trained on us. She was eager for handouts and unafraid. We handle them a lot when young, and I’ve taught them to come when called. Punny Chun, who’s a Dorking, a breed believed to date back to the Roman Empire, has these pink five-toed feet at the end of squat little legs. She looks like a big dove, coos like a dove, and is loving as a dog. She follows us around to be picked up and petted, but don’t mess with her. She is, after all, a little dinosaur, and she’s already worked her way toward the top of pecking order. She lords it over most of the other hens, even our mean menopausal eight-year-old, Bluebeard.

KJ: In reviews, your work has been likened to Delillo, Pynchon, and others. Do you consider any of these authors to be an influence?

JBN: Yes.

KJ: What’s next for you?

JBN: Backgrounded by my window on the Midwest are some of the key ingredients. I’m refining the recipe, making a terrible mess in the kitchen, and hopefully someday it’ll yield something palatable.

**

Jay Baron Nicorvo is the author of a novel, The Standard Grand (St. Martin’s Press, 2017), and a poetry collection, Deadbeat (Four Way Books, 2012). He lives on an old farm outside Battle Creek, Michigan, with his wife, Thisbe Nissen, their son, and a couple dozen vulnerable chickens. Find Jay at www.nicorvo.net.