Interview: Jay Rubin

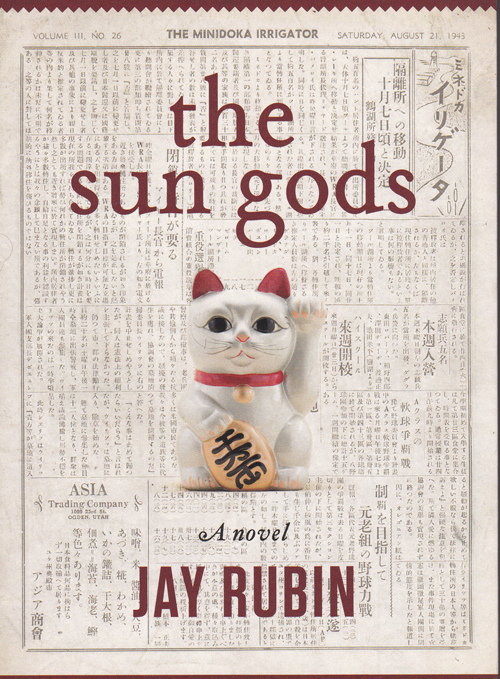

Midwestern Gothic staffer Stephanie Mezzanatto talked with renowned translator and author Jay Rubin about his new novel The Sun Gods, translating Murakami, America’s Japanese internment camps, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Stephanie Mezzanatto talked with renowned translator and author Jay Rubin about his new novel The Sun Gods, translating Murakami, America’s Japanese internment camps, and more.

**

- Stephanie Mezzanatto: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Jay Rubin: The University of Chicago. I transferred in as a second-year undergraduate in 1960 and finished my Ph.D. in Japanese literature in 1970. I lived in Burton-Judson my first year, and in a series of Hyde Park apartments most of the rest of the time–one of the most memorable of which was right next to the Illinois Central tracks and had soot blowing in the windows. I went to The Blue Flame and other blues joints, saw Muddy Waters and Buddy Guy a few times, B.B. King at some big theater, the Paul Butterfield Blues Band in various clubs and on campus, saw Thelonious Monk at a Near North jazz club, took part in the folk music revival, learned to play the guitar, which I still do often enough to keep my calluses intact.

SM: The Sun Gods tells the story of a widowed pastor, Tom, who falls for one of his congregants, a Japanese woman, Mitsuko, on the eve of World War II. Tom, Mitsuko, and Tom’s son, Billy are soon torn apart when Mitsuko and Billy are sent to Minidoka Internment Camp. Bill later returns to his father, but two decades afterward, he ventures on a journey to find Mitsuko and learn the truth about their past. What inspired your decision to focus your debut novel on the World War II era?

JR: At the UC, I studied Japanese language and literature, had no particular interest in the Japanese-American experience until one day when I was in graduate school my professor happened to mention the so-called relocation camps in which 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry were confined during the war. I was shocked to learn that our country had had its own concentration camps right here within our own borders, and almost as deeply shocked that I had managed to remain ignorant of them into my mid-twenties. I started reading about the period but never thought to write about it until after I moved to Seattle in 1975 and started meeting people who had actually been locked up. Even then, the desire to present the experience in a viscerally palpable form didn’t gel until 1985 when my wife and I started discussing a suitable story. Much prewar Japanese-American social life was based on church membership, so something church-connected seemed a logical way to probe the atmosphere of the times.

SM: What do you hope to enlighten readers about concerning the Japanese internment camps? What drew you to highlight this infamous time period in our nation’s history?

“Infamous” indeed! One source of mine, Michi Weglyn’s Years of Infamy: the Untold Story of America’s Concentration Camps (1976), turned the tables on FDR’s famous branding of December 7, 1941 as “a date which will live in infamy.” Richard Reeves picks up the irony in his encyclopedic Infamy: The Shocking Story of the Japanese American Internment in World War II (2015). I couldn’t find a publisher interested in the story when the novel came together in 1987, but the atmosphere is very different now with the 70th anniversary of the end of the war. Now perhaps the broader American public will allow this truly “shocking story” to penetrate its stolid consciousness. I hope that my book’s emotionally-charged presentation will make an impression where more objective treatments have been less successful.

SM: You received your PhD in Japanese literature from the University of Chicago. How did the interplay of Midwestern culture and Japanese culture influence your writing and learning while in Chicago?

JR: The one element of Midwestern culture that might have fed into my concern with the concentration camps was the sizeable Japanese-American community in Chicago. Most of those people found their way there from the West Coast during the “relocation” period. I remember once being invited to a New Year’s Day celebration held by the huge extended family of a Japanese-American classmate. I learned to eat Japanese food in Chicago, and I often visited the Toguri Mercantile Company owned by the family of the woman accused of being Tokyo Rose.

SM: Can you give prospective readers an insight into how Christianity and other spiritual belief systems guide and complicate Bill’s path as he ventures to Japan to find his adoptive mother? Why did you decide to make religious belief systems form such an important component to this novel?

SM: Can you give prospective readers an insight into how Christianity and other spiritual belief systems guide and complicate Bill’s path as he ventures to Japan to find his adoptive mother? Why did you decide to make religious belief systems form such an important component to this novel?

JR: If there’s a single theme running through the book, it is that of hypocrisy–the hypocrisy of a supposedly Christian nation treating a minority ethnic group like cattle, and the hypocrisy of imprisoning that group while mouthing American ideals of equality under the law. Even the Supreme Court cooperated in this outrage, twisting itself into logical pretzels to invalidate the Constitution. With its emphasis on love and goodness, Christianity at its best encourages genuine compassion and social activism, but it also has a special tendency to convince its believers that they are virtuous children of God no matter what they do (invading Iraq, for example). As Bill becomes disillusioned with the empty rhetoric with which he was raised, and he encounters Shinto’s expression of simple gratitude for the good things in life, he becomes sensitized to the innate holiness of life devoid of fairy tales.

SM: You have been successful for many years as an English-language translator of Japanese literature, former professor at the University of Washington, then Harvard University, and author of Making Sense of Japanese, a widely used guide to Japanese language studies. What influenced your decision to branch out into writing your own fiction?

JR: Anger and shame, to put it succinctly. Anger at the racism that inspired the incarceration and shame at my own ignorance of the camps. I know it looks as though I have suddenly “branched out into writing fiction,” but I wrote the book before I had ever heard of Haruki Murakami.

SM: What was the biggest challenge you had to overcome while writing your first work of fiction, that you haven’t faced before in nonfiction and translation?

JR: That blank computer screen. When you’re translating, you have somebody else’s images feeding into your imagination before you start to write, and with nonfiction you’re synthesizing information or interpreting texts. The scariest thing about writing your own fiction is the freedom to turn the story in any direction at any point. You want to make a novel feel unpredictable in prospect and inevitable in retrospect. Like life.

SM: What settings (time, place, etc.) do you find most productive for the stimulation of creative thought? What steps do you take to overcome writer’s block?

JR: I do all my writing in the morning. If something is percolating, my brain wakes me as early as 5:30 and keeps me going until it poops out, usually around noon. Deadlines are great for overcoming writer’s block.

SM: What’s next for you?

SR: My translation of Murakami’s interviews with the conductor Seiji Ozawa should be coming out from Knopf next year in some kind of e-book form that will give the reader immediate access to the music under discussion. I’ve been so busy with The Sun Gods since it was accepted by Chin Music Press last June that I have gotten sidetracked from the project I’m supposed to be working on, a book of modern Japanese stories for Penguin. It won’t be the usual chronological compilation but will group the stories into categories–Japan and the West, Warriors Loyal and Otherwise, Modern Life and Other Nonsense, Men and Women under Stress, Disasters Natural and Man-Made, etc. Working at my current pace, I should have my next novel ready for publication in March 2045.

**

Jay Rubin (b. 1941) has translated and/or written about the Japanese novelists Haruki Murakami and Natsume Soseki (1867-1916), the short story writers Kunikida Doppo (1871-1908) and Akutagawa Ryunosuke (1892-1927), prewar Japanese literary censorship, Noh drama, and Japanese grammar. His novel THE SUN GODS appeared in May 2015. Rubin has a Ph.D. in Japanese literature from the University of Chicago. He taught at the University of Washington for eighteen years, and then moved to Harvard University for thirteen years, retiring in 2006. He lives near Seattle, where he continues to write and translate.