Interview: Sophfronia Scott

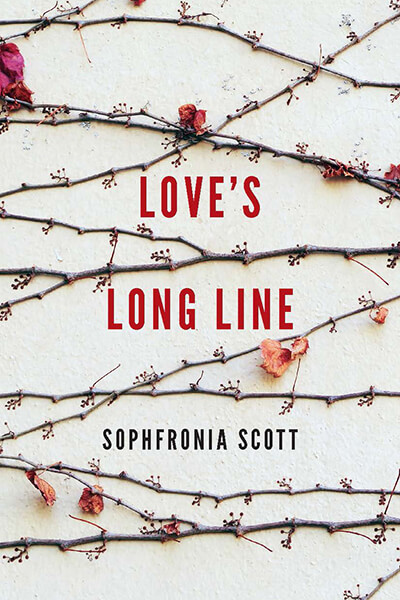

Midwestern Gothic staffer Marisa Frey talked with author Sophfronia Scott about her book Love’s Long Line, solitude vs. loneliness, love and faith in everyday life, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Marisa Frey talked with author Sophfronia Scott about her book Love’s Long Line, solitude vs. loneliness, love and faith in everyday life, and more.

**

Marisa Frey: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Sophfronia Scott: I was born and raised in Lorain, Ohio—yes, Toni Morrison’s hometown! And my husband is from Brook Park, a Cleveland suburb located about 30 miles west of Lorain. We live in Connecticut now, but we both have family still in the area so we travel back to Ohio once or twice a year. However I believe you can leave the Midwest but the Midwest doesn’t leave you. I lived in New York City for most of my adult life but strangers would always ask me where I was from because it was obvious to them that I wasn’t from New York. I once asked someone who said this how he could tell. His answer? “You look too clean.”

MF: Your collection Love’s Long Line was inspired by a line from Annie Dillard’s Holy the Firm: that we all “reel out love’s long line alone…like a live wire loosed in space to longing and grief everlasting.” Can you discuss this intersection of loneliness and grief with love and vulnerability? What is the importance of loneliness?

SS: I don’t think of “alone” in terms of loneliness. I think of it in terms of solitude or singularity. Solitude provides the space that allows an individual to learn/confront/understand the depths of one’s own heart. This is important because in any relationship (Dillard was talking about relating to God but I see this in all relationships—parents, spouse, etc.) it is only our own hearts we can really know. That love exists in our heart is a vital acknowledgment, but it’s also where the vulnerability comes in because that love exists regardless of whether or not the other person returns it or is capable of returning it. And even if they do, you never know if they can meet you with the same intensity/level where you love. You can end up, as Dillard puts it, “holding one end of a love” and it’s up to you how you live that love—or become frustrated or hurt by it.

I think you have to hold on and be true to your heart. You live the love. Having such an open heart can leave you open to experiencing a lot of grief, but there is joy to be had as well. You have to go for it.

MF: Love’s Long Line includes essays about your father and your experiences as a mother. What did you discover about yourself and these relationships while writing?

SS: Writing about my father is really a continuation of the writing about him that I first did when I was in college. At first I was surprised that I still wanted to write about him, but then I realized—with some relief—that the new writing affirmed what I learned all those years ago, that love and forgiveness were still present, still holding strong. I’m so grateful for that.

As I observed in the essay “White Shirts,” it feels like there’s a grace reaching me across the years showing me how much I still care. My father died 27 years ago but he is still that present for me.

As a mother I’m learning, as many of us do when we get older, why my father made certain choices—why, for example, he pushed my siblings and I to write things down because we were forgetful. I see that same forgetfulness in Tain, who is 13, now—I think puberty fogs the brain!

But I’m also realizing that Daddy recognized my autonomy—that as scary as it was for him, he knew and had to accept I would be in the world apart from him. I sensed my son’s autonomy almost from the moment he was born. I’ve managed to move away from the scary aspect so I don’t parent from a place of fear. I’m also not afraid of expressing affection so Tain knows he is loved. He won’t have to seek out clues as I had to do with my father.

MF: Love’s Long Line has been described as “clear-sighted” and “wise and ruminative.” Did you approach the essays with an idea of the message you wanted to relate, or did you find yourself writing your way into it?

SS: I didn’t begin with a message in mind. My essay writing is my way of thinking out loud. I start with an idea and then leave myself open to the discovery process. Only when I started assembling the essays as a collection did I begin to see the connections and how it all made me think of Dillard’s Holy the Firm. I felt as though I could see her observations at work in my life, and that I was saying something, maybe even responding to her thoughts, about love and faith in everyday life.

I think or ruminate about things a lot. Essay writing has given me a place to put all these thoughts that have been stewing a good long time. I suppose the results are, by nature, bound to be rich, like a savory beef bourguignon cooked for hours and hours.

MF: You’ve previously worked at Time and People—how did your experiences there influence the way you write now?

SS: At both Time and People magazines I frequently had to write short articles, 500 words and less. Those short articles still had to be packed with information and the prose had to pop. Writing like that taught me to respect words. Every word has to pull its weight when you write short, every verb has to be on target. I’ve carried that respect into my fiction and essay writing. My books may be over 100,000 words but none of those words are throwaway words.

MF: Do you find writing novels and essay collections requires a different mindset than writing and editing at Time and People?

SS: Well, my work ethic is the same. I don’t have any angst in getting down to work so that mindset is the same. What’s different is my voice. The magazines each have their own voice, their own tone, and writers have to work with that sound and still be interesting and edgy and proper. It’s been a journey for me to understand what I sound like and I’m constantly experimenting with the best ways to bring who I am to the page. Recently Time asked me to write a piece for their website and I have to admit, that was satisfying, to have my voice requested for Time’s space.

MF: You work with different forms—fiction, nonfiction, essays, novels—how does your approach to writing change with each?

SS: When I write fiction it’s like I’m planting seeds. I have some sense of what I’m planting and in the writing process I see what grows and how it grows. I know, for example, that I must write a dialogue scene between two characters. I approach that work knowing some of what they will say to each other but leaving room for surprises as well. All this discovery can take place within one writing session.

Nonfiction writing is like digging but I don’t know what I’m digging for and I don’t know what I’ll find. Sometimes what I find takes me in unplanned and often unsettling directions. That discovery takes time. An essay could take weeks, even months, and I have no way of knowing what that timeframe will be. I’ve learned to be patient with myself and to give myself as much space as possible to do the thinking and searching required for such work.

What is the best writing advice you’ve ever received?

SS: A few years ago I’d read a piece in the New York Times that bothered me so much I could feel it churning within me. I knew I was going to write something when I woke up thinking about the subject and as I sat up in bed I heard the voice of Bret Lott in my head. He said, “Don’t get too preachy Scott!” I worked with Bret in my final semester as an MFA student and honestly I can’t tell you whether he ever actually said those words to me or if I only dreamed them that morning. But since Carl Nagin, my writing teacher in college, said something similar to me I believe there is a truth to this advice so I pay attention to it. I’ve distilled it down over the years to this essence: If I speak and write from a place of quiet conviction—“this is what I know and feel”—then I don’t have to preach.

MF: What are you reading right now?

SS: The Color of Water by James McBride, This Could Hurt by Jillian Medoff, and You Must Change Your Life: The Story of Rainer Maria Rilke and Auguste Rodin by Rachel Corbett.

MF: What’s next for you?

SS: I won’t go into details now but I’m working on a novel of historical fiction. It’s set in various states (Louisiana, South Carolina, Ohio, New York) in Civil War era America. I’m also gathering string on pieces that I hope will become another essay collection. I like this rhythm of going back and forth between fiction and nonfiction so I figure I’ll just keep going with it.

**

Sophfronia Scott was a writer and editor at Time and People before publishing her first novel, All I Need to Get By (St. Martin’s Press). Her latest novel is Unforgivable Love (William Morrow). She’s also the author of an essay collection, Love’s Long Line, from Ohio State University Press’s Mad Creek Books and a memoir, This Child of Faith: Raising a Spiritual Child in a Secular World, co-written with her son Tain, from Paraclete Press. Sophfronia teaches at Regis University’s Mile High MFA and Bay Path University’s MFA in Creative Nonfiction. She lives in Sandy Hook, Connecticut. Her website and blog are at www.Sophfronia.com