Interview: Matthew Vollmer

Midwestern Gothic staffer Jo Chang talked with author Matthew Vollmer about his collection Permanent Exhibit, editing being an exercise in curation, writing for an audience in real-time, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Jo Chang talked with author Matthew Vollmer about his collection Permanent Exhibit, editing being an exercise in curation, writing for an audience in real-time, and more.

**

Jo Chang: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Matthew Vollmer: I spent my first quarter as a college freshman attending a Seventh-day Adventist university in Berrien Springs, Michigan. I don’t think the sun came out once when I was there. I’m sure that can’t be true, but I seem to remember that there was some kind of precipitation every day I lived there–fog, mist, drizzle, downpour, sleet, snow, you name it. So, partly because of the weather, and partly because Berrien Springs was perhaps the loneliest and dullest place I’d ever lived–the highlight of the three months I lived there were the few trips out of town I’d taken with friends who had cars, one of which ended at Medusa’s, a Chicago nightclub which featured a statue of the eponymous snake-headed woman crucified to a cross–I transferred to another SDA college in midwestern Massachusetts. Eight years later, in the year 2000, I followed my wife to Lafayette, Indiana, where she began pursuing a PhD in Rhetoric & Composition from Purdue University. We lived in a duplex. Our neighbor was a sweet, toothless woman who smoked Mistys and cleaned houses. Across the street: an Apostolic church and school, and listened to them sing hymns on Sunday mornings. I taught composition, business writing, and public speaking to kids who’d grown up detasseling corn and who listened to bands like Staind and Linkin Park and Staind Puddle of Mudd. One summer, in an attempt to “clear my head,” I joined an entomology field crew and we drove all over Indiana, visiting stainless steel vats that had been inserted into corn fields and filled with antifreeze to attract and kill whatever bugs wandered by. My wife and I visited Chicago every February because my mom traveled with my father there for a dental convention, and suffered wind-burn as we negotiated the icy sidewalks of “Magnificent Mile.” Once our son was old enough to sit in a backpack, I spent hours every day walking–through rain and snow and sun and humidity–the streets of Lafayette, a town that initially I didn’t much like, but then began to find elements I could appreciate, like, for example, the Ben Hur tavern, with its life-size cardboard cutouts of NASCAR drivers and limited drink menu (Bud, Bud Lite, red wine); or the cobblestone streets of Highland Park, whose mansion-sized homes I liked to glance into after sunset; or the grotto behind the Catholic church, with its shelves of flickering or dead candles; or the mannequin heads inside the beauty college; or the bright red of McCord’s Candy shop; or the sushi place whose legendary owner might make you wait for an hour for an entree and ban you forever if you complained; or the Wabash River, whose waters I once paddled in a boat with my fisherman friend Henry, who persisted with his line and pole for over an hour to reel in a catfish the size of a grown man’s torso, and whose body, once it was drawn up to the surface, resembled the flesh of the Swamp Thing.

JC: You have ties to both the South (North Carolina, Virginia) as well as the Midwest (Iowa, Michigan). Have the regional differences ever come into play in your writing, in terms of finding inspiration, navigating new spaces, or anything in between? What do you carry with you from the Midwest?

MV: I think every story I’ve ever written–and every essay–is grounded deeply in place. Having grown up in a relatively isolated part of the country–southwestern North Carolina–and in a cove at the foot of a mountain that stood at the edge of a very small town–1600 people–place has always been very important to me. Back then, as a kid, I wanted nothing more than to leave the valley where I’d grown up. Other places–especially urban places–seemed somehow more “real” to me. Now it seems that the reverse is true: as soon as I step into woods, I feel comforted by the swaying limbs of trees, who seem to be saying: See? This is what it’s all about.

What do I carry with me from the Midwest? Long, straight highways. Storm systems. Tornado sirens. Farmhouses. Barns. Lone trees in soybean fields. Steakhouses with garish wallpaper and tassled lamp shades. Churches. Caramel apple pie. Library book sales. A local weatherman named “Buzz.” Tiny American flags. Immaculate lawns. Basketball hoops. Chain restaurants. Strip malls. Peyton Manning jerseys. Cubs hats. P. T. Cruisers. Wind. Snow. Sunburns. Elephant ears. Corn fields.

JC: Do you feel as if your experience as both an author and an editor has shaped and/or altered your creative process? Do elements of being an editor affect your writing process as an author, or vice versa?

MV: Yes? I mean, I don’t know how much “real” editing I’ve ever done, aside from the work of commenting on manuscripts of friends and students. The two anthologies that I worked on–Fakes and A Book of Uncommon Prayer–didn’t require the kind of line-by-line attention to detail or the eye-in-the-sky POV that I associate with editors like Karen Braziller, who I worked with on my story collection Gateway to Paradise. (Karen made it clear from the very beginning that even though the majority of the stories had appeared in magazines, that we were making a book, and there were extensive revisions that could and should be done, and in some cases, we ended up moving through a dozen or more drafts of individual stories.) Fakes and A Book of Uncommon Prayer were more like exercises in curation; material had to be selected and then arranged–the structure of the resulting manuscript had to “make sense.” Maybe the most apt comparison would be the arranging of a playlist. I suppose there’s some crossover there in terms of what I’m working on now: a longer, book-length narrative which is composed of many fragments. Figuring out what should go where–and how and when to juxtapose or put like kind next to like kind–ends up being a big part of the process.

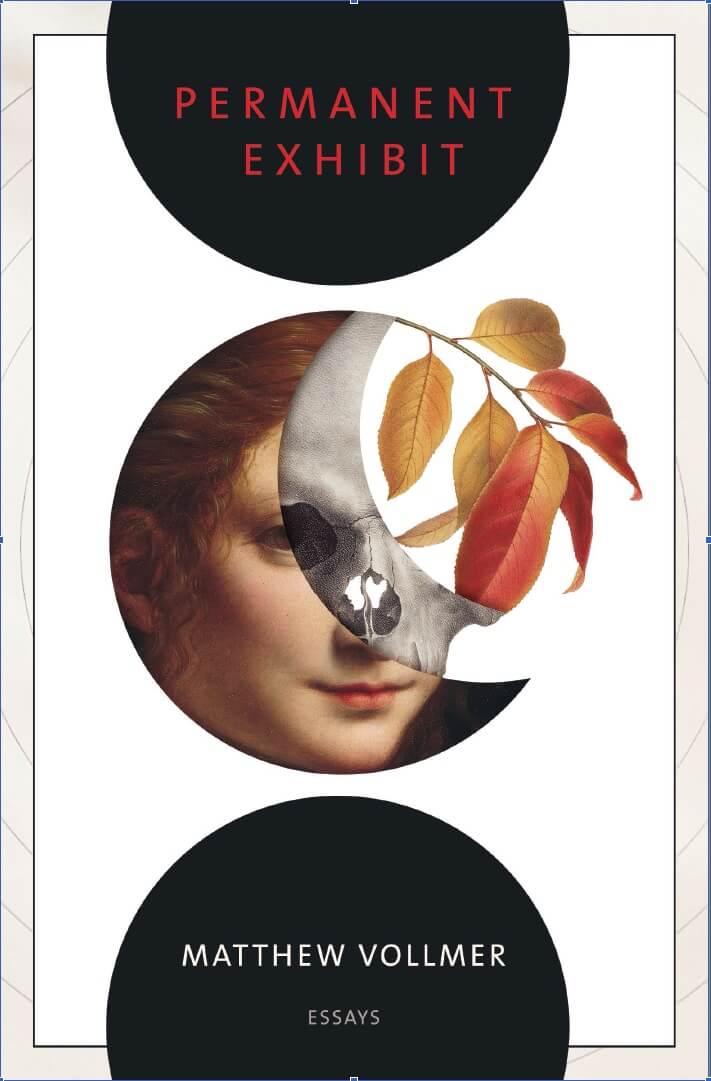

JC: Your fourth and forthcoming book, Permanent Exhibit, is a short prose collection that was originally published as a series of status updates on a social media platform. The collection includes an array of updates that encompass everything from the playfully random to the serious and morbid, offering a new perspective on a portrayal of a “slice of life.” Where did you gain this inspiration initially, and for the book?

MV: One night, during the summer of 2016–on July 6, to be exact–I wrote a status update that I thought was a kind of anti-status-update. It was basically a mini-collage that represented some of that particular day’s events as well as some random thoughts I’d entertained: how surreal it seemed that, at this late date in history, homes were still being raided for marijuana; that I’d eaten a piece of pizza big enough to wrap around my face; that I’d seen, during a bike ride, a mother deer nursing her fawn in the middle of the road; that I didn’t get all the New Yorker jokes; that a chipmunk lived in my basketball; that Earth was a planet I lived on. I didn’t really think much of what I’d written; I was simply recording whatever images, thoughts and impressions that occurred to me at the time, partly as a response to every other status update I’d read, which had seemed, perhaps due to the outrage that fueled them, to be highly political, and very intentional. I then hit “POST” and went to bed. When I got up the next morning, I noticed that my most recent update had been liked nearly 100 times, which is about 95 more than I was accustomed to receiving. Intoxicated by this outpouring of admiration, and the spirit of renewal that comes with finding a new form in which to inhabit, I tried writing another essay, in a similar style and mode. In a post reacting to this second attempt, a friend and former teacher of mine–the writer Chris Offutt–told me to “keep going with this approach,” and another acquaintance–the writer Peter Cherches–asked if I was going to write a book in this manner. I said I didn’t know; a friend of mine I’d met twenty years before, during the summer I worked as a waiter at the Old Faithful Inn in Yellowstone National Park, said, “I’m pretty sure you’re stoned and I like it” (I hadn’t been, but whatever.) I liked the attention and liked that I could curate–in a medium that seemed to be reserved, especially of late, for the outraged and the outrageous–a little space for meditation and reflection. So I kept writing a little essay every day, in a similar style, letting myself be led by association, not knowing what I was going to write about or where it would lead me, just making myself do it, and assigning myself to write one every day for ten days straight, which I did. One might think it would get easier as the days went by; it didn’t. Writing every day was one thing, but completing something every day–even if it was only about 1000 words–was another. The number of likes I was getting wasn’t growing, but I still had the sense that people were reading–in fact, people I knew who hadn’t “liked” or commented on the updates would comment on them in person, said they were reading them with interest. It felt sort of like a performance, like I was writing for an audience in real time, even though that wasn’t exactly the case. Still, the anticipation of those dopamine-inducing likes kept me going, and though I didn’t continue to finish an essay every day, I continued posting frequently over the course to the next six months. By the end of the year, I had a manuscript’s worth.

JC: Could you say something about the title of the book, and what it means in relation to its message?

JC: Could you say something about the title of the book, and what it means in relation to its message?

MV: “Permanent Exhibit” is the title of one of the book’s essays. In it, I ruminate about the secret burial mounds of Cherokee Indians that my father told me one of his patients knows about, which leads me to “I don’t know how long you have to be dead before it’s okay for archaeologists to dig you up, but I like to think about in-the-future humans plundering my grave, wouldn’t mind donating my body to science, as long as my skull became a prop on someone’s desk, like the skull that used to sit on the desk of my Uncle Rick-Rick, who used it as a macabre puppet and referred to it as Mr. Bones. Perhaps I could arrange for my skull to be turned into a kind of permanent exhibit; using animatronics, the skull would live in a cube—in a museum? a cemetery? the family graveyard?—where its jaw would move, and speakers would play words that I’d written, and perhaps it would even read what I’m writing right now, and tell the story of the dead snake I saw on Catawba Road, and that I had seen it alive, in the same place, two days before: enrobed in lustrous black scales, and presumably attracted to the heat conducting properties of the asphalt, it had laid on the shoulder in a luxuriant tangle.” In this context, “permanent exhibit” is a literal thing: an exhibit made, after my death, of my bones.

“Permanent Exhibit” also seemed an apt title for the book as a whole, since its content was first displayed on social media. I don’t necessary think of Twitter feeds and Facebook streams as “permanent,” despite the fact that content lives on in archives, mostly because I–like most people, I assume–read one thing and then move on to the next. There’s this sense that anything anybody posts is “of the moment” and–like moments–passes away and/or is forgotten. I liked the idea of titling a book Permanent Exhibit, then, because it was and wasn’t true. We like to think of books as things that are more or less immortal, that “live on” after their authors die, but it’s also true that 99% of books published are completely forgotten. And even those who do achieve “immortality” will have to reckon with whatever ravages humans inflict on this planet, to say nothing of what happens when our sun, whose ever-increasing brightness will someday be enough to evaporate our oceans, scorches the last human out of existence, about one billion years from now.

JC: Since Permanent Exhibit utilizes status updates as an art form, do you feel like social media has influenced your development as a writer, such as acting as either a positive influence or a hindrance in your writing process?

MV: It’s definitely served as an influence. I don’t know if it’s safe to say that it’s a bad influence, even though it certainly has changed the way that I operate as a human (20 years ago I did not pick up a little rectangular piece of glass and chrome and aluminum and silicon and tap and swipe its surface for half an hour. My phone connects me to friends and family and news outlets and games and banks and theaters and investment companies and the weather and sports music and TV shows and movies and a program that can listen to and identify whatever song I’m hearing. That’s pretty cool. But it’s also a huge distraction. I don’t see writers writing about that experience enough. Think about opening Safari on your phone and seeing all the open browser windows. Right now, scrolling through mine I see news about my son’s friend who won the state tennis title, the for sale page for a weird local house I recently visited, an unsubscribe page for Carolina Beach Realty, a photo and description of a shoe in the style of the Air Jordan 2, a LIFE magazine from 1957 wherein a trip to a jungle to eat magic mushrooms is documented; a Facebook status update from a fellow colleague imploring us to vote in Virginia’s primary; a page displaying the lyrics to the hymn “How Great Thou Art”; a video of John Oliver lambasting Sean Hannity for generating the “S**ttiest Conspiracy Theory Ever”; an outdated weather report; a map for a nearby hiking trail; a recipe for “Middle School Tacos”; and a recap for Westworld, Season 2, Episode 7. What a weird conglomeration of things to scroll through! And yet these seemingly disparate subjects represent a history of things I’ve thought about and interacted with. What kinds of things could I write about if I could harness both the content and the actions associated with my life online? That’s sort of what I tried to do with the essays in Permanent Exhibit–and I found that following my associations not only seemed to legitimize my internet surfing, but also freed me from the kind of linearity that the narrativizing of one’s life imposes.

JC: Do you think utilizing social media will become a necessity for upcoming writers who wish to promote their work, as a promotional tool? Does social media compromise the fine line between the art and the artist? What long-term effects do you think this relationship will have, either positive or negative, if any?

MV: I hate that writers are expected to promote their own work via social media. I mean, that may sound weird, given the fact that I am publishing a book whose content first appeared on a social media platform, but sharing one’s writing feels much different than sharing the news about one’s writing. Or about one’s publications. Or awards. Or whatever. Many of my close friends seem to have unplugged altogether and I think this–the idea that you, as a successful user of social media, need to be constantly posting and re-posting and making steady and frequent contributions to whatever feeds you belong to–is the reason that they left. There’s a lot of noise. There’s a lot of outrage. And self-promotion. I usually feel worse after having visited Facebook or Twitter. And I think that was part of the initial impulse with writing the essays that make up Permanent Exhibit. I wanted to somehow use the power of social media for good. I wanted to do something positive, to approach the idea of the status update with earnestness, curiosity, and feeling–so as to make something worthwhile.

JC: What’s next for you?

MV: I’m working on another book, a kind of Permanent Exhibit 2.0 It’s an extended meditation on death, memory, replication, religion, mysticism, God, mountains, boarding school, church, family, reading, language, and story. It’s called All of Us Together in the End, and its refrain comes from the first lines of the Dhammapadda, which say, “we are what we think/ with our thoughts we make the world.” I guess it’s a narrative that tries to explain how, specifically, I have used thoughts to make my world, and where those thoughts came from–how I was raised in a church that taught me that I should reject the world, and then what happened when I embraced it. It’s coming together, but I have a long way to go.

**

Matthew Vollmer is the author of two collections of short fiction—Gateway to Paradise (Persea, 2015) and Future Missionaries of America (MacAdam/Cage, 2009; Salt Publishing, 2010)—as well as a collection of essays—inscriptions for headstones (Outpost19, 2012). His work has appeared widely, in such places as Paris Review, Glimmer Train, Tin House, Virginia Quarterly Review, Epoch, Ecotone, New England Review, The Sun, Best American Essays, and The Pushcart Prize Anthology. With David Shields, he co-edited FAKES: An Anthology of Pseudo-Interviews, Faux-Lectures, Quasi-Letters, “Found” Texts, and Other Fraudulent Artifacts (W. W. Norton, 2012), and served as editor for The Book of Uncommon Prayer (Outpost19, 2015), an anthology of everyday invocations featuring the work of over 60 writers. His next book—Permanent Exhibit—will be published by BOA Editions, Ltd. in 2018. He teaches at Virginia Tech.