Interview: Bao Phi

September 7th, 2017

Photo credit: Thaiphy Media

Midwestern Gothic staffer Kathleen Janeschek talked with poet Bao Phi about hatred from lack of understanding, approaching his work naturally, being a champion slam-poet, and more.

**

Kathleen Janeschek: What is your connection to the Midwest?

Bao Phi: Even though I was born in Vietnam, my family fled and came to the Phillips neighborhood of South Minneapolis when I was a baby. I’m pretty much a lifelong Minnesotan.

KJ: How does the varied geography of Minnesota inform your writing?

BP: When I was very young, I remember my family had a lot more connection with rural people in Minnesota. I think because we came from a country that was still very close to agriculture. We would go out to farms fairly often, and buy vegetables and meat directly from farmers. And farmer’s markets every weekend. But Phillips, where I was raised and where my parents still live, is very much the inner city – Minneapolis’s largest, poorest, and most racially diverse neighborhood. The Little Earth housing projects is two blocks from my parent’s house, and the Franklin Avenue Library, where I learned to love books, about six blocks away. My dad would often take me on fishing trips, sometimes by a mucky pond by the highway, sometimes renting a trailer at Mille Lacs. Not for sport, but for food. I got to know the city by skateboard in my junior high days, and as I got older, I go out to Greater Minnesota, sometimes for work, sometimes as a tourist. My father always tried to instill an appreciation for nature in me, and I am trying to pass that along to my daughter.

KJ: In which ways do the people of Minnesota contrast with the landscape of Minnesota?

BP: It’s funny, in the old days, I felt like the people we met in rural areas of Minnesota were more open to us. They approached us with curiosity and were very friendly, whereas people in the city seemed really racist and violent and intolerant. Families like mine were often blamed for the Vietnam War, even though my father fought on the same side as the Americans – people didn’t understand, and back in the old days it seemed like most of that hate was in the city. In terms of the people and contrast – that’s hard to say, honestly. I’ve lived here so long that I’ve gotten to meet all different types of Minnesotans, so I find it difficult to generalize. I would say the perception of Minnesotans by outsiders, however, is that we are unsophisticated, boring, minor. I don’t think that’s true, obviously.

KJ: Your poems often switch between conversational and formal language. Is this transition intentional or something that naturally occurs in your writing?

BP: It’s a combination of how I write and what happens during the editing and revision process. It’s also probably about who I am – I went through a creative writing program, but as a spoken word artist, back when the idea of a spoken word artist going through a creative writing program was somewhat rare. I also often think of something the great poet R. Zamora Linmark advised me: “don’t edit the duende out of your poetry.”

KJ: Likewise, many of your poems include words or phrases from Vietnamese. What do you hope to achieve from this medley of languages?

BP: It’s just a part of who I am. I try not to force it – I tend to use it as I would naturally use it in real life, especially with the newer work.

KJ: In American discourse, there is often a conflation between the black experience, urban experience, and poor experience. How do you seek to challenge these narratives in your writing?

BP: First of all I think it’s tremendously important to lift up and support Black, urban, poor voices and art. Simultaneously it is important for us to challenge the dominant racist archetype of the Asian as the successful, overachieving model minority that doesn’t struggle against racism in this country, or against empire and colonization. I think the key word there is simultaneously – because often, we in America get caught in binaries and competition. Asian American struggle is often obscured by the model minority myth, but I want to make it clear that this is not the fault of Black people and Black voices. Those of us on the margins – Black, Native, Asian American, Latinx, Arab, Middle Eastern, Queer, Women, and all intersections of those identities – often get boxed into one or two simplistic narratives. My hope is to challenge and explode those simplistic, un-nuanced narratives.

KJ: How do your Vietnamese and Asian identities influence your writing? Do you ever find these identities at odds with one another?

BP: Tricky. I think Viet Thanh Nguyen, author of The Sympathizer, said it best: many of the contemporary Asian American movements are rooted in the collision of third world alliance, Marxism, and socialism, but many Vietnamese in America are here due to conflict with the Communist Party of Vietnam, and so a lot of Asian American liberation rhetoric can be triggering for Vietnamese people, especially of a certain generation. It’s a challenge that should be familiar to all writers: how do you stay true to your ideals and beliefs while not alienating your community – and how do you do that artistically? It’s a constant struggle.

KJ: You’re also a slam poet–and a two-time Minnesota Grand Slam champion and a National Poetry Slam finalist–so what has slam poetry taught you about written poetry?

BP: Urgency, passion, overcoming your fear, communicating difficult ideas and stories to an audience. But honestly that’s where my interest in poetry was before I slammed. I was in Speech Team, Creative Expression, at South High school back in 1992 and 1993. We were one of the few inner city schools that competed in Speech back then. So usually I was competing against suburban white kids who wrote funny essays, and here I was, this intense, awkward, Vietnamese refugee from the hood with braces and bad acne doing angry poems about racism. Sometimes it went over surprisingly well, and sometimes, well, you can guess some of the comments I got from the white suburban judges. You know, racism doesn’t exist, anger isn’t the answer, etc. But all of that prepared me to create armor for myself.

KJ: Are there any notable differences in your creative process when working with slam poetry or written poetry?

BP: No. I write poetry, and then I figure out what’s the best way to perform that poetry in front of an audience. The reading/performance of poetry is, in itself, craft.

KJ: What are some of your greatest influences in media other than writing (eg: film, music, art, etc.)?

BP: Everything – movies, television, comic books, all types of books (moving for me always sucks because of my book collection), music, table top role playing games, video games.

KJ: What’s next for you?

BP: I’ve been pretty much writing a poem a day for the last two or three years, though sometimes I take a “vacation.” I’m kind of writing a fractured memoir in verse, kind of writing some poems about a Chinese delivery boy who opens a door to an alternate dimension. I’m a single co-parent, so i’m trying to raise a kid while working as Program Director at the Loft and continuing my artistic practice. I have my first children’s book, A Different Pond, illustrated by the great Thi Bui and published by Capstone, coming out this summer, and my daughter has requested my next children’s book be about her. I’m looking at two bedroom domiciles for me and my daughter on one person’s salary which puts me in competition with dual income households with no children in a cutthroat housing market, which means I picked a bad time to get off anti-depressants.

**

Bao Phi is a two-time Minnesota Grand Slam champion and a National Poetry Slam finalist whose poems and essays are widely published in numerous publications including Screaming Monkeys, Spoken Word Revolution Redux, and the 2006 Best American Poetry anthology. The spoken word series he created at the Loft Literary Center, Equilibrium, won the Minnesota Council of Nonprofits Anti-Racism Initiative Award. His second collection of poems, Thousand Star Hotel, was also published by Coffee House Press on July 5, 2017, and his first children’s book, A Different Pond, illustrated by Thi Bui, was published by Capstone Press in August of 2017.

Natalie Teal McAllister’s story “If There Was Ever a Time” appears in Midwestern Gothic‘s

Natalie Teal McAllister’s story “If There Was Ever a Time” appears in Midwestern Gothic‘s

Tanya Seale’s story “Dissolving Lori” appears in

Tanya Seale’s story “Dissolving Lori” appears in

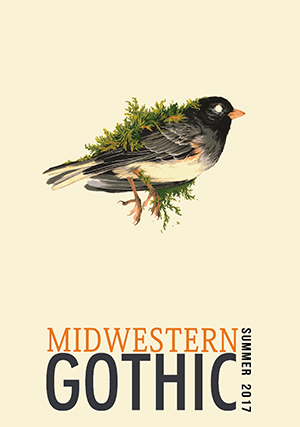

Just in time for the tail end of summer, we’re thrilled to announce that the Midwestern Gothic Summer 2017 issue is here!

Just in time for the tail end of summer, we’re thrilled to announce that the Midwestern Gothic Summer 2017 issue is here! Harris Lahti’s story “Highways of Damage” appears in Midwestern Gothic‘s Summer 2017 issue, out now.

Harris Lahti’s story “Highways of Damage” appears in Midwestern Gothic‘s Summer 2017 issue, out now.