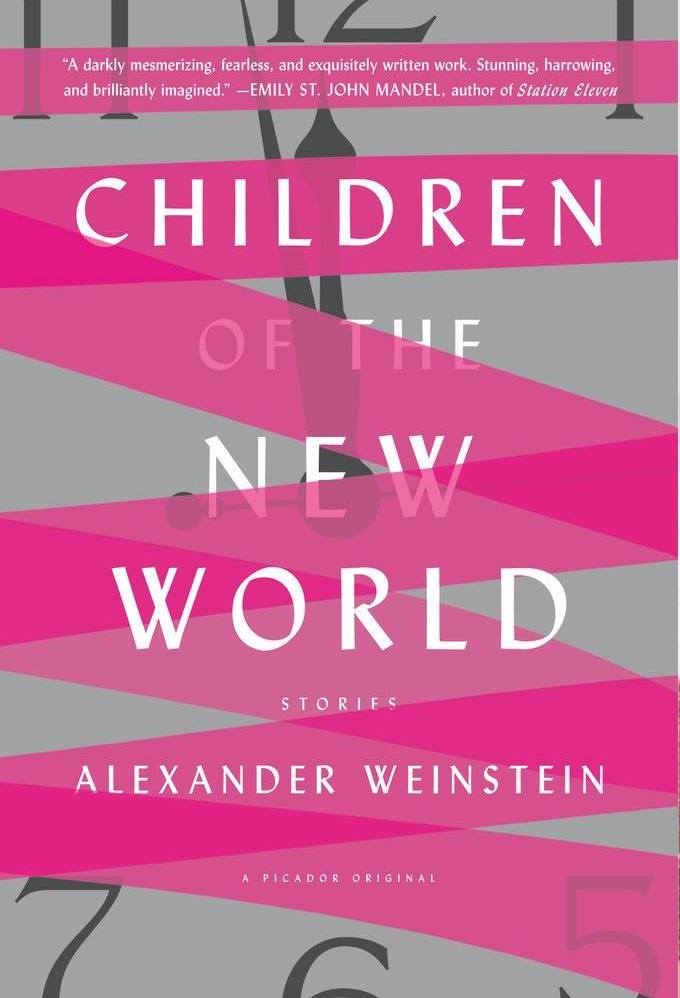

Midwestern Gothic staffer Kristina Perkins talked with author Alexander Weinstein about his collection Children of the New World, the relationship between technological and interpersonal connection, finding hope in dystopia and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Kristina Perkins talked with author Alexander Weinstein about his collection Children of the New World, the relationship between technological and interpersonal connection, finding hope in dystopia and more.

**

Kristina Perkins: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Alexander Weinstein: I’m originally from New York, and came to the Midwest by way of Portland, Oregon (where I was a chef for many years) and Boulder, Colorado (where I finished my undergraduate degree at Naropa University). I first came to the Midwest when I entered Indiana University’s MFA program in Bloomington, and then six years ago I moved to Ann Arbor for my teaching position.

KP: How has the Midwest — as a place, a community, and/or a value system — influenced your writing?

AW: It’s been an interesting mix of compassion, joy, and despair! The final story in the collection, “Ice Age”, came about from the first winter I spent in Michigan. We were covered in perpetual snow and ice, and I felt like I was living through an ice age! There’s also a great deal of urban decay and economically devastated communities throughout Michigan, which has led to the socio-economic and environmental settings which appear in the collection. There have been travesties of justice throughout Michigan. Our governor, Rick Snyder, knowingly switched the city’s water source and so poisoned the families of Flint. So this kind of political crime is far beyond any dystopia I could dream up in my fiction. Detroit, which is nearby, contains post-apocalyptic landscapes while also birthing urban-farming and re-inhabited art and community spaces—and this speaks to a kind of dystopic hopefulness that underlies the collection.

So that’s the element of despair that I’ve felt in the Midwest. As for compassion and joy, I’ve been raising my son here in the Midwest, and our relationship brings a great amount of joy to my life. This element of parenthood plays a big part in the collection. I also think there’s a real genuineness and kindness underlying Midwestern sensibilities. In many ways, there’s a lack of pretentiousness in the Midwest (in particular, the uber-hipsterism which one can find in many coastal cities) and I admire this Midwestern honesty. I remember one winter, when my car went off the road during a snowstorm, there were literally dozens of people who stopped to help me and my family. Perhaps this level of human kindness is present throughout the US, but I’ve noticed it in particular since moving to the Midwest.

KP: Your debut collection, Children of the New World, focuses on the (often times inverse) relationship between technological and interpersonal connection. How would you describe your own relationship to technology — not as only a writer, but as a teacher, father, and community member?

AW: There are a great number of social/political ways that the internet helps us — we learn about social injustices around the world thanks to the internet, and we’re able to protest and create human rights movements due to the networking capabilities technology provides. All of which I use the internet for. One can also download great spiritual talks from thinkers like Ram Das, Rabbi Zalman, Terrance McKenna, or the Dalai Lama. In this way, there’s a wonderful availability of spiritual teachings thanks to technology — and I often listen to these podcasts and find them very enriching.

Of course, the internet isn’t good or bad, it all depends on how we use it. But my fear is that we’re not really using it that well. The endless emailing and texting, the spambot click-bait, and the millions of mini-games out there — it all creates an intense addiction to our devices. I find myself checking my phone 30-40 times a day, at red lights I send off a last text to someone—these are behaviors symptomatic of addiction. So, while I certainly use/need technology on a daily basis, I’ve been making an effort to disconnect. I leave the phone at home now, am considering reinstalling a landline, and try to avoid screen time as much as possible. I’ve even started calling people instead of texting them (what a bizarre idea-right!) And I’ve been working with my son to help him not overuse technology, since I think these issues of addiction are all the more severe for the generations raised with devices.

KP: You’ve said in previous interviews that, despite their themes of dystopia, anxiety, and fear, your stories are ultimately hopeful. When crafting your stories, how much are your plots influenced by this sense of optimism?

AW: I put a good deal of importance on hopefulness and human kindness within my writing. I really do want my stories to inspire positive change in the world — whether it’s due to a sense of optimism, empathy, a desire for human love and connection, or for activism. For this reason, it’s particularly hard when I have a darker story come to me.

For example, the story “Heartland” is one of the most devastating stories in the collection. The parents in that story are struggling so deeply, and the decisions they are forced to confront are awful ones that I’d never want anyone to have to make. While writing that story, I really struggled against my own sense of optimism. The story doesn’t match up with my hope for the world, and originally I tried to make the story a humorous one to lighten the mood (if you know the story: a clearly asinine endeavor). This attempt — to superimpose my own philosophical desires on the story — made the story unwriteable for two years. I finally had to get myself out of the way and allow the story to be told in the tone it demanded.

KP: Why do you think science fiction writing places so much emphasis on the dystopian, the post-apocalyptic? Should we make more room for utopian literature? Put another way: what is the relationship between dystopia and utopia, both in Children of the New World specifically and sci-fi generally?

AW: Well, we’re certainly living though rough times. Fracking is making our water flammable, police are killing innocent black people with seeming impunity, there’s a legal system increasingly set up to protect corporations, and in North Dakota, the tribes of all nations have been amassing to protest the seizing of their lands by oil companies and are facing brutality from the National Guard. These are huge social, environmental, and human rights issues (just to name a few). When I look at these issues, I see a world much more dystopic than anything I could come up with. So I think sci-fi writers are often looking critically at the world, and dystopian stories offer social critique and literary activism. Certainly the stories in Children of the New World are working in this vein.

And yet, I’m totally fascinated by this idea of a new utopian literature. In many ways, I feel like our art forms (particularly in the past 40 years) have been largely informed by a kind of ironic/cynical stance. Intellectual acuity has gone hand in hand with a kind of jaded, ironic cynicism. There are many writers who I admire that revel in this cynicism — David Foster Wallace is a prime example. There are of course exceptions to this rule (Italo Calvino and Tom Robbins) but largely we’ve been in the business of cynicism for the past couple decades. This makes me think that there may be an unexplored genre out there: one which utilizes the emotion of unabashed joy as its central motivation. I’ve been thinking a lot about the jubilant story. What does a story look like that takes the tone of a praise poem? A story which sings? This sort of story would somehow have to celebrate the mystery of being alive, of human kindness, of love, compassion, and care. I think the poets are already exploring this terrain much more readily than fiction writers. I really love Ross Gay’s collection, Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude — which has an incredible amount of love and praise for humanity. The question a more utopian literature raises is how one deals with conflict? Perhaps, the very notion that fiction needs conflict is merely a remnant of the older models of narrative (which are intrinsically linked to cynicism). Are there other craft techniques that would supplant the element of conflict in a more utopian literature? I don’t know the answers to these questions, but the idea of the joyous story is always simmering in the back of my mind.

KP: The landscapes of Children of the New World are decidedly futuristic: your characters live in societies where clones, robots, and even virtual sex games are commonplace. Despite this technological futurism, you’ve mentioned that you consider your work more as speculative fiction than traditional sci-fi. Why do you make this distinction? What, to you, are the benefits of this sort of genre hybridity?

AW: Since I don’t get into the actual science behind the technology, my stories don’t fall into the technical category of sci-fi. Scientific believability is often a badge of honor for sci-fi writers — deservedly so — and because of this, I feel that my work is speculative rather than scientific. My focus on the very human dramas of life (the struggle to love well, to be good parents, to navigate relationships) also shares a great deal with the genre of literary realism. So the genre labels of speculative fiction and slipstream work well for covering both of these terrains. All that said, I’m not a huge fan of siphoning literature into genres — I’m much more for letting all genres (sci-fi, detective, mystery, adventure, humor, absurdity, realism) come under the heading of simply “Fiction.”

KP: I was wondering if you could talk a little more about your creative writing program at Martha’s Vineyard. Why did you start it? What drew you to an island off the coast of Massachusetts?

AW: When I first became a writer, I imagined I’d be entering into an actively artistic community, full of late night dinners, philosophical conversations, impromptu poetry readings, etc. And there have been times of such artistic collaboration in my life and also throughout history (the Expatriates in Paris, The Beat Generation, etc.) But I was surprised to find that the writing life was much more solitary than I’d expected, often fraught with faceless rejections, and unfortunately besieged by internal hierarchies and competition. This idea of a hierarchy (and it appears in writing programs where only “the best” student writers get to work with “the most prominent” faculty) was completely antithetical to what I considered an artistic community.

So in 2010 I founded The Martha’s Vineyard Institute of Creative Writing in order to create a summer writing program where writers of all ages and experience levels could work together in a supportive and craft-intensive environment. The founding goals were to minimize competition and nurture cooperation, craft, and community. MVICW is also specifically focused on breaking down the hierarchies and literary egos which can arise in more competitive programs, and promoting a model of inclusivity. Attendees work closely with the visiting faculty, there are evening readings, craft seminars, and faculty and attendees celebrate with a dinner together — so it creates a much more intimate and creative environment (the kind I’d hoped for when I first became a writer).

Every year I’ve been inviting award-winning authors, poets, and literary journal editors to come to MVICW as faculty. Since we are a non-profit organization, our mission is to help writers in financial need, and I’m engaged in fundraising and grant writing to create fellowships for writers who would benefit from the program but couldn’t otherwise afford to come. Over the past seven years we’ve been able to offer dozens of scholarships to writers, and my hope is to eventually have a fully endowed program.

As for Martha’s Vineyard, my family has our home on the island, and so it’s been my home for a long time. The island has a really rich history of supporting literature and the arts, and it’s also one of the most beautiful places I know. So I wanted to share this place, which means so much to me, with other writers.

KP: Who is your favorite contemporary author, and what type of inspiration do you draw from their work?

AW: Can I name more than one? If so: Tom Robbins, Ishmael Reed, Tatyana Tolstaya, George Saunders, Karen Russell, Ludmilla Petrushevskaya, Michael Martone, Steven Millhauser, Victor Pelevin…I could go on. I love how each of these writers experiments with the borders of fiction and the so-called “rules” of literature.

KP: What’s one thing you wish you had known when you first began writing?

AW: The number of rejections inherent in finding success! We’re talking hundreds upon hundreds of rejections — which is par for the course.

KP: What’s next for you?

AW: I’m presently working on my second book with Picador, The Lost Traveler’s Tour Guide, a novel comprised of tour guide entries that describe fantastical cities, museums, libraries, restaurants, hotels, and art galleries — each one a universe unto itself. It works primarily in the vein of Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities, and Milorad Pavic’s Dictionary of the Khazars. It’s also a kind of autobiography, as each of the destinations is a metaphor for the emotional locations I’ve visited: museums of longing, hotels of joy, cities of heartbreak. Whereas Children of the New World has ties to sci-fi, this new book is rooted in magical realism. All the same, I’m still working with my favorite topics: nostalgia, longing, memory, and love.

**

Alexander Weinstein is the Director of The Martha’s Vineyard Institute of Creative Writing and the author of the short story collection Children of the New World (Picador 2016). His fiction and translations have appeared in Cream City Review, Hayden’s Ferry Review, Pleiades, PRISM International, World Literature Today, and other journals. He is the recipient of a Sustainable Arts Foundation Award, and his fiction has been awarded the Lamar York, Gail Crump, Hamlin Garland, and New Millennium Prize. He is an Associate Professor of Creative Writing and a freelance editor, and leads fiction workshops in the United States and Europe.

Ben Tanzer’s piece “Never Better” appears in Midwestern Gothic Issue 23, out now.

Ben Tanzer’s piece “Never Better” appears in Midwestern Gothic Issue 23, out now.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Megan Valley talked with author Gary Amdahl about The Daredevils, musing vs. building, radical labor activism and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Megan Valley talked with author Gary Amdahl about The Daredevils, musing vs. building, radical labor activism and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Lauren Stachew talks with author Tiffany McDaniel about her novel The Summer that Melted Everything, what’s in a name, midwestern gothic as a genre, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Lauren Stachew talks with author Tiffany McDaniel about her novel The Summer that Melted Everything, what’s in a name, midwestern gothic as a genre, and more.

Christi R. Suzanne’s piece “Whispers” appears in

Christi R. Suzanne’s piece “Whispers” appears in  Toni Nealie’s piece “The Sediment of Fear” appears in

Toni Nealie’s piece “The Sediment of Fear” appears in

Midwestern Gothic staffer Kristina Perkins talked with author Alexander Weinstein about his collection Children of the New World, the relationship between technological and interpersonal connection, finding hope in dystopia and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Kristina Perkins talked with author Alexander Weinstein about his collection Children of the New World, the relationship between technological and interpersonal connection, finding hope in dystopia and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Sydney Cohen talked with author Daniel Raeburn about his book Vessels, looking for a home, birth and death and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Sydney Cohen talked with author Daniel Raeburn about his book Vessels, looking for a home, birth and death and more.