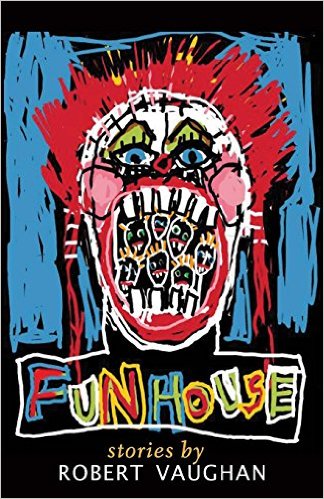

Midwestern Gothic staffer Megan Valley talked with author Bryn Greenwood about her novel All the Ugly and Wonderful Things, spiritual claustrophobia, cannibalization of the heart, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Megan Valley talked with author Bryn Greenwood about her novel All the Ugly and Wonderful Things, spiritual claustrophobia, cannibalization of the heart, and more.

**

Megan Valley: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Bryn Greenwood: My family originally came from England to Ohio, and from there to Kansas. We’ve been here ever since, even through the Dust Bowl. When I’m overseas, when people ask where I’m from, my instinct is always to say Kansas, rather than The United States, even if that requires me to explain what and where Kansas is. (It’s the big rectangle in the middle of America! is my go-to line.) This is such a big country and I’ve met so many fellow Americans who were as alien to me as someone from another country, that it makes sense to identify myself by my cultural roots rather than by my nationality.

MV: While much of your life you’ve lived in Kansas, you also taught in Japan for a time. What made you return to Kansas?

BG: After Japan, I lived in Florida, and as strange as it will seem to outsiders, it was the landscape that made me come back to Kansas. In both places, I lived in very dense metropolitan areas with heavy vegetation, and in Japan, I lived at the western edge of the Honshu mountain range, what people call the Japanese Alps. It turned out that I don’t thrive in situations where I can’t see the open horizon easily. I could travel for hours and still not be able to see enough open space to alleviate my anxiety. And for a girl raised out in Western Kansas, the ocean is in no way the same. It’s actually a little terrifying. Hemmed in by buildings and trees and mountains and water, I felt spiritually claustrophobic, if that’s a thing. I remember the first week I was back in Kansas, I drove out to see my sister, and as I was passing through the Flint Hills, I had to pull off on the shoulder of the highway. I felt like could finally breathe again, and it was a little overwhelming.

There’s a lot of that open sky aesthetic in All the Ugly and Wonderful Things. I have so many fond childhood memories of being out under the night sky, surrounded by open fields, far away from towns and roads.

MV: What did living in Japan teach you about yourself?

BG: Nothing flattering, honestly. I learned that even in such a fascinating place with so much cultural history, I still preferred to be alone and to read books. I saw a lot of Japan, but I also spent a lot of nights holed up in my tiny apartment doing what I would have done in Kansas: reading.

I also learned that you can take a redneck out of the wheat fields, but she will promptly attach herself to the cultural equivalent thereof wherever she goes. In my first six months in Japan, I got in trouble for dating the local Kawasaki motorcycle mechanic. Having grown up the granddaughter of poor, dirt farmers, I didn’t realize that in Japan, teachers are a professional class, like doctors and lawyers, so it was considered inappropriate for me to be romantically involved with someone who had not attended high school, and whose parents were rice farmers. My boss made me end the relationship, because that’s how things work in rural Japan. As a single woman, I was expected to defer to my boss as a stand-in for my father.

MV: You refer to yourself as the daughter of a “mostly reformed drug dealer,” and your novel, All the Ugly and Wonderful Things, focuses on Wavy, the daughter of a drug dealer. How do you use inspiration from your life in your writing?

BG: I think writers are like boxes of baking soda that you put in the ice box to absorb odors. We soak up everything around us, sometimes without even realizing it. When I started All the Ugly and Wonderful Things, there were scenarios and situations that I drew directly from what I’d experienced with my father’s life. Armed compounds out in the middle of nowhere and drug-fueled parties attended by people both unsavory and extraordinary. I don’t know that I could have written those things if I hadn’t witnessed them. There were other more subtle things that I didn’t even recognize until much later: turns of phrase and physical characteristics that I unwittingly borrowed from real people, and real emotions that I revisited. Even though the book isn’t autobiographical, like Wavy, I had a passionate affair with a much older man that started when I was thirteen. In going over the book for final copy edits, I could see the places where I cannibalized my own heart to describe joy and loss. I think that’s the work of writers.

MV: You have a WordPress blog where you interact a lot with reader’s comments and questions. Why do you think this is important to do?

BG: For me, one of the most important things about fiction is that it creates dialogue. If I write something and a reader responds, I want to interact with that reader, because that’s how we create understanding, empathy, compassion. I love talking about books, my own and others, just to exchange ideas and impressions with other readers. I’ve had a fair amount of hate mail over this book, but as long as a reader is polite and sincere, I’m still interested in talking to someone who is angered or troubled by the story I told. It’s not meant to be an easy, comfortable story. Why shouldn’t people be upset about it? The only people I don’t talk to are the ones who say, “You shouldn’t have told this story.” I won’t waste my time justifying my work to people who think I don’t have a right to express my own experiences and my own feelings.

MV: Also on your blog, you’ve said that when you read about writing, you don’t write anything because it makes you question yourself. How, then, would you say you approach writing?

BG: So often, essays on writing end up being prescriptive, even when they don’t intend to be. So if I read too much about the craft of writing or the philosophy of writing, I suffer from the same performance anxiety I used to have when my eighth grade English teacher called me to the board to diagram sentences. Then I’m too much in my head, worrying about whether I’m doing this “right.” As soon as I start questioning my approach to writing or my technique, I freeze up and stop writing. When the writing is going well, I simply submerge myself in the characters and their desires. Later, after I have the story down, I can worry about things like, “Did I use this word too many times? Is this a cliché? Am I emotionally manipulating the reader? Is this in fact the forty-seventh character I’ve written with abandonment issues?”

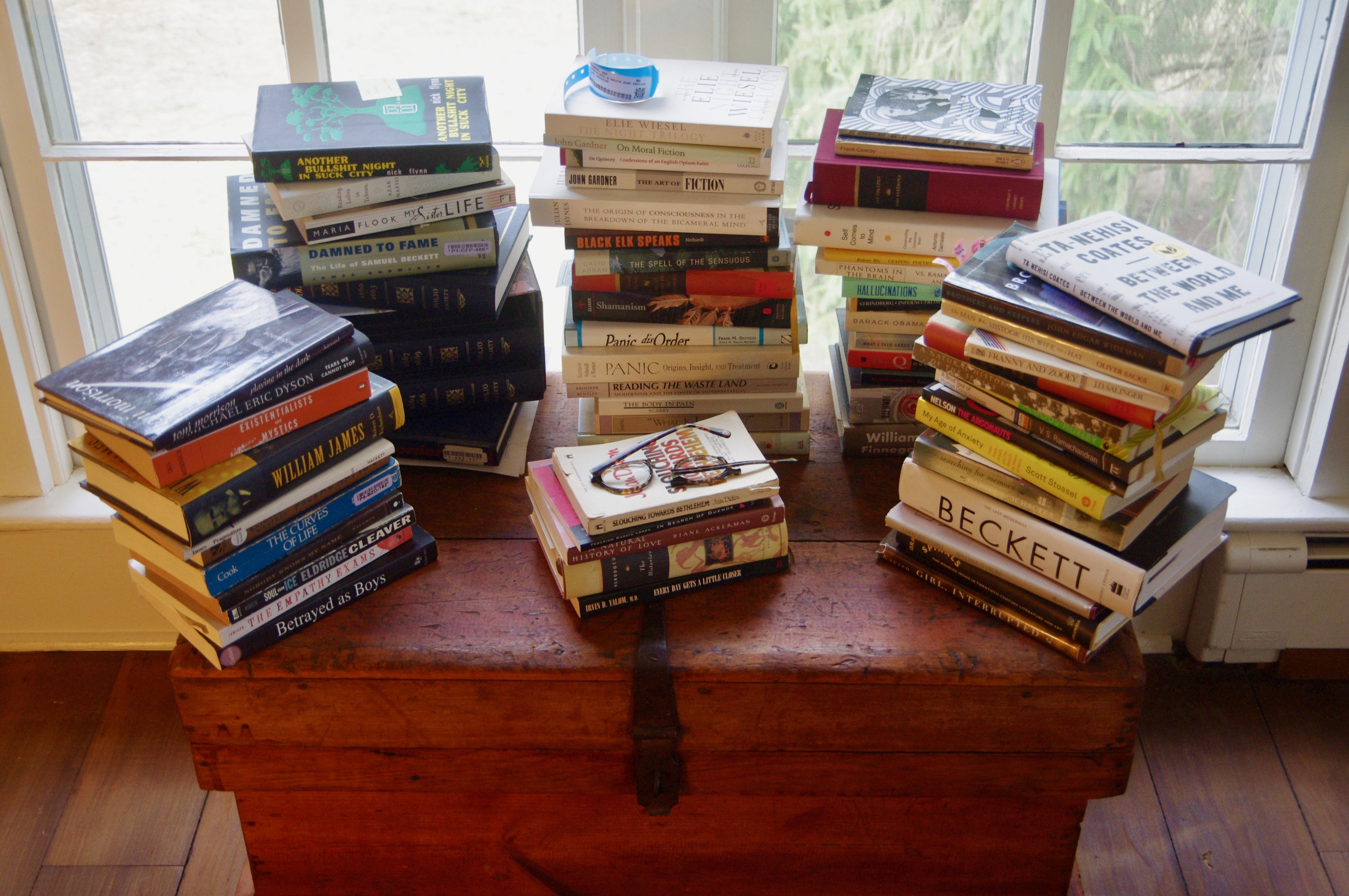

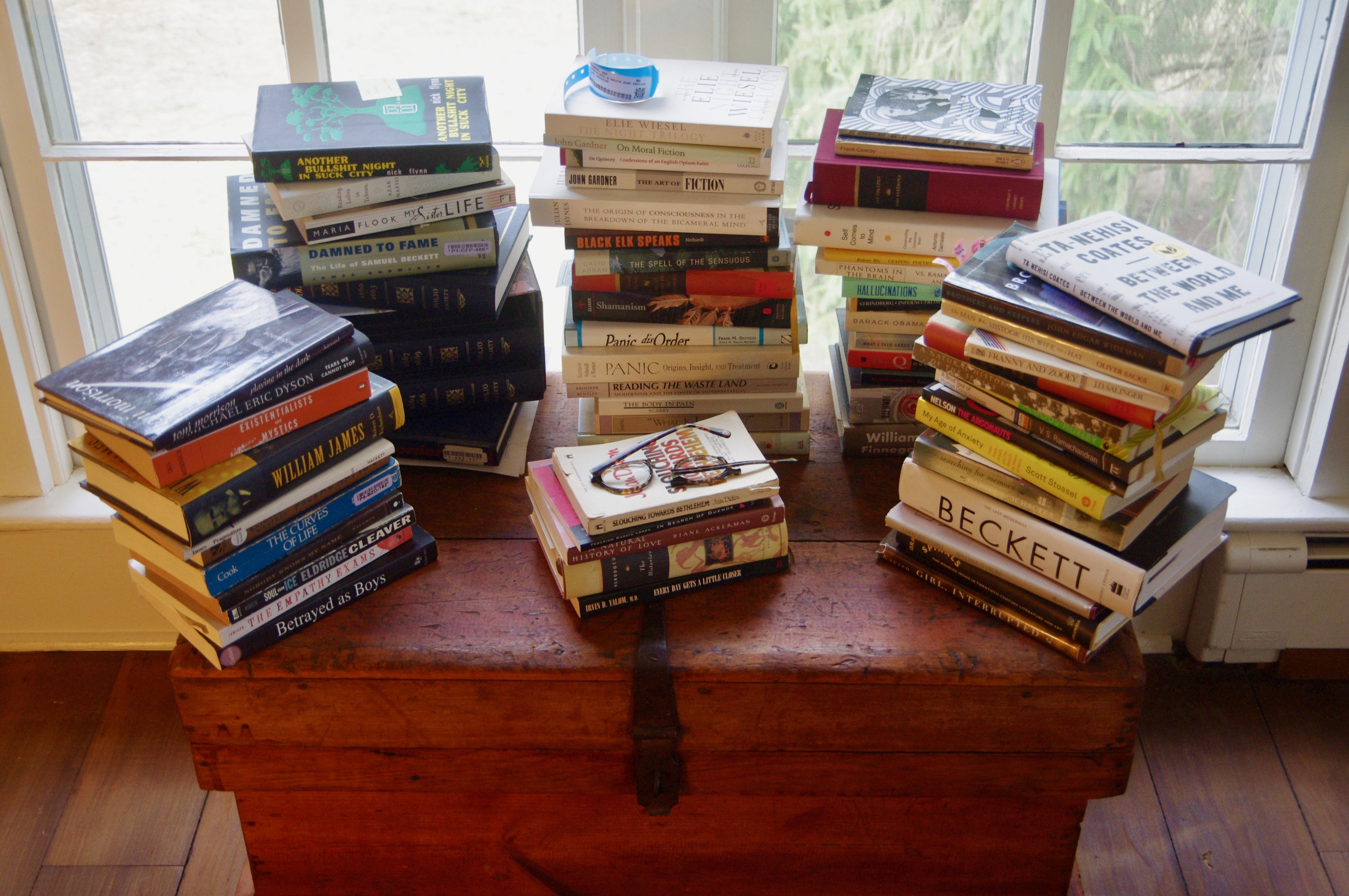

MV: Relatedly, you’ve said your greatest pleasures are those moments when you’re reading something that makes you forget you’re a writer. What are some of the books that have given you that pleasure?

BG: Obviously, there are likely tons that I read before I become so aware of how being a writer changed me as a reader, so I’ll just name some more recent ones off the top of my head, without even checking my reading list, because they’re ones that have stuck with me so firmly.

The Mount by Carol Emshwiller

Effigy by Alissa York

The Turner House by Angela Flournoy

Relief Map by Rosalie Knecht

Of course, I often reread books like this in order to look at how the writer has done what they did, but there’s so much joy on a first read in being immersed in a story and not giving a moment’s thought to how the story has been crafted.

MV: There are sixteen narrators in All the Ugly and Wonderful Things. How do you craft that many distinct voices within one book and why did you decide this was the best way to tell your story?

BG: Confession: all my stories start this way. I love the way every character brings their own experiences and their own biases to a story, so even when I know I won’t have a place for a particular character’s narrative, I like to investigate how they see things. In case they have some important insight that I don’t. This book is just a large scale example of that approach. Because of the nature of the story, and the way it divides people, I wanted to reveal a lot of it from people who are at the periphery of the action. In some ways, it’s like a fictional documentary, as though I went around and interviewed all these people who had some small piece of the story.

In terms of making all the voices distinct, I only hope I was mostly successful. Where there was a clear divide between the educational and socio-economic classes of characters, it was much more straightforward. Where I was dealing with characters who were of similar backgrounds, I had to make much finer distinctions. For example, I had two working class men from the same small Kansas town, both with middle school level education, both mechanics by trade, one older and widowed, one younger and unmarried. I had to look closely at word choice and speech patterns to distinguish them by age, by personality trait, and even religious beliefs. On a surface level, they have similar voices, but they swear differently, they have different conversational tactics, they have differing outlooks on such amorphous things as hope, faith, love, friendship.

MV: What’s next for you?

BG: Most definitely there are more multiple-POV stories ahead for me. The project I’m currently working on revolves around a set of triplets, so there are three characters right off the bat. That same project has me obsessing over the idea of “normalcy” when it comes to our physical selves. So much of a person’s identity is wrapped up in the body that person inhabits, and even more of the world’s perception of a person is about the physical body.

**

Bryn Greenwood is a fourth-generation Kansan and the daughter of a mostly reformed drug dealer. She earned a MA in Creative Writing and continues to work in academia as an administrator. She is the author of All the Ugly and Wonderful Things (August 2016, Thomas Dunne Books) and the small press novels Last Will and Lie Lay Lain. She lives in Lawrence, Kansas.

May 4th, 2017 |

Midwestern Gothic staffer Audrey Meyers talked with poet Keith Taylor about his collection The Bird-while, writing as a life-long identity, the paintings of Vermeer, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Audrey Meyers talked with poet Keith Taylor about his collection The Bird-while, writing as a life-long identity, the paintings of Vermeer, and more.

**

Audrey Meyers: What is your connection to the Midwest?

Keith Taylor: I first moved to the Midwest – South Bend, Indiana – over 50 years ago. After spending a few years away, I returned to live in Michigan. I’ve been lucky here: I married a woman from Detroit and I’ve had good work that has allowed me time to write. And think. The attitudes of the Midwest have become my attitudes.

AM: How has living in Ann Arbor impacted your writing?

KT: Oh, Ann Arbor is an easy place for writers to live. Bookstores! Readings regularly at the University or around town. A general attitude that a life in the arts is possible and reasonable. There is a large community of the arts here and most people can find the support they need. And there are places to publish!

I think I would have become a writer without Ann Arbor, but I would have been a very different writer.

AM: As a creative writing professor at the University of Michigan, how does the classroom and your students affect your writing?

KT: Mostly, to be around serious young students of writing, the professor has to try to keep up with the new work that is being done in the country, the work that is influencing the students. That keeps my reading fresh, and keeps me reevaluating my own work. I think that is a necessary part of the process.

I came back to teaching rather late. I was 47 years old when I left bookselling to focus on teaching, so it is different for me than for many writer/teachers. I never expected to have these long vacations, this institutional intensity focused on the work.

AM: Since The Bird-while is your 16th collection of poetry, what inspires you to keep writing?

KT: At some point – maybe 20 or 25 years ago – it became clear to me that I was a writer whether I wanted to be or not. And this had only a little to do with the actual making of books. Not only was the act of writing essential to my self definition, but it had become the way I think. The way I understand the world. Now, I would be lost without it.

AM: Nature, the spirit, and mind are prominent themes in your book. How do they interact and relate to one another? How do you express this in poetry?

KT: Wow! That’s a big question! Millions of pages have been written on this — not only in Western philosophy but in Buddhist philosophy too. And I don’t have an answer for it. But there is something in the image – in finding the image in the world and then finding the words to recreate the image. Something there. We reach out past mind to the world and the distinctions disappear. Gary Snyder – wise poet and life long student of Zen – entitled his selected poems No Nature. If there is no distinction between mind and nature, then there is no nature. But it is hard to write this quickly. It sounds too easy.

AM: Where did you spend your time writing The Bird-while? In other words, what setting helped you to create these poems?

KT: Most of my work this last decade has been written in my little house on the west side of Ann Arbor or in a little cabin up at the University of Michigan Biological Station, where I’ve had the pleasure of teaching for the last dozen summers. I do keep a journal and it goes with me everywhere I travel, so ideas get jotted down around the world. But the poems mostly take shape at home.

AM: Your book is uniquely structured by not having section breaks. What does this style accomplish for your poetry? What motivated you to make this choice?

KT: Yes, thanks for noticing! My sense is that the process of thinking, of experiencing the world that goes into a book of poems – and for me, into this book in particular – was not broken into units. Yes, there are clusters of poems related by image or idea, but they are connected to other clusters. I didn’t want a big break between them like a numbered section would indicate. I imagined the breaks as hesitations. I was going to leave blank pages, but then it occurred to me that I could get my old friend Tom Pohrt to do illustrations for those moments. I feel very fortunate that he agreed.

AM: What life experiences influenced your poetry in The Bird-while?

KT: Oh, all my life experiences influenced the book! But that’s too easy. Certainly, my own aging is a part of this book, a recognition of the exquisite small moment. There are lots of moments of my reading in here, sometimes obvious, and sometimes quite hidden. But I am a person of books and I bring them with me even when watching birds. Museums have always been important to me. And there are several museum moments in this book. Travel, of course. Maybe travel is less important in this book than it has been in some earlier ones, but it is still here – even if some of travel recounted is from my daughter’s trips rather than mine.

AM: How did you implement Emersonian sensibility into your poetry?

KT: I’m not sure I set out to implement Emerson in my work, but I have studied him closely at different times in my life. His idea of being open to the natural world, the giant eye-ball, has always interested me, but more as a description of things I already sensed in myself than as something I had to impose on myself. There is a radical uncertainty in Emerson, and I cherish that.

AM: What were your main challenges when writing these poems?

KT: The challenges never seem to change. I have to find the time to make poems in a world that really doesn’t care whether I make them or not. And even now, in my mid-60s, I have to convince myself that the process and the poems themselves are worth the time. Perhaps no artist is ever free of self-doubt, but we have to recognize it and resist it all the time.

The world presents endless subject matter for poems, but not all of that can get into my poems. I have to find the right words for the things that need to be in my poems. That challenge will never end.

AM: What do you hope readers take away from your poetry?

KT: Another tough one. Yes, I have hopes for my readers, even if they are not front and center in my mind in the moments of composition. I hope I can communicate something of the exquisite facts and mysteries of the world. Of my experience of it, anyway. I would hope readers might share that and might be pleased by the words I found to express it. That’s a lot to hope for, I know. It might be impossible.

AM: What’s next for you?

KT: The poems won’t end. Even as I’m working on a chapbook sized collection of short poems about my neighborhood, I’m beginning to take notes on three larger poems, three that might make a book all on their own. They are poems that contain information and thinking and that move slowly through thought. I’m not sure I can write them the way I’m imagining them now.

I have two bigger prose projects in mind – and I think I have to quit working before I can sit down and work on those. I’m going to stop working for the big University in a year or so, mostly to get to these projects.

And I’ve decided there are a couple of things I want to see of the world before I leave this vale of tears. I want to officially see 1,000 species of birds. That’s about one-tenth of the birds on the planet, and it can be done quite easily. I’m at 680 right now. I’ll have to do some more trips to interesting places.

And I want to see all the paintings of Vermeer. My reasons for this are various, but it’s mostly because they are small, exquisite, so clearly done with love, and are so important to the development of the modern artistic temperament.

I haven’t really intended to write about these two “projects” at all, until someone suggested to me that 35 Paintings and a Thousand Birds is a pretty good title. We’ll see.

**

Poet and writer Keith Taylor teaches in the undergraduate and graduate programs in creative writing at the University of Michigan, directs the Bear River Writer’s Conference, and is the poetry editor for Michigan Quarterly Review.

His sixteenth collection, The Bird-while, was published by Wayne State University Press February 2017. Fidelities was published in 2015 by Alice Greene & Co. Keith’s work has appeared in such publications as Story, The Los Angeles Times, Alternative Press, The Southern Review, Michigan Quarterly Review, Notre Dame Review, The Iowa Review, Witness, Chicago Tribune, and Hanging Loose. Other books are Marginalia for a Natural History published by Black Lawrence Press, and Ghost Writers, a collection of ghost stories co-edited with Laura Kasischke, published by Wayne State University Press.

April 28th, 2017 |

Midwestern Gothic staffer Kristina Perkins talked with author Marisa Silver about her book Little Nothing, the importance of place, the elasticity of time in fiction vs. film and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Kristina Perkins talked with author Marisa Silver about her book Little Nothing, the importance of place, the elasticity of time in fiction vs. film and more.

**

Kristina Perkins: What is your connection to the Midwest?

Marisa Silver: I was born in Cleveland, Ohio and lived there until I was seven.

KP: You’ve spent much of your adulthood in Los Angeles; in fact, The New York Times has called you “one of California’s most celebrated contemporary writers.” How has your understanding of place — be it the Midwest, Southern California, or elsewhere — influenced your identity as a writer?

MS: Place functions as more than mere scene setting. For me, place is a component of character. We exist in places, we are formed, in part, by particular environments. Our behavior is often inextricably linked to where we are. How we negotiate a street, drive in the car, walk on a path, how we experience rain or heat, how we respond to the prevailing cultural norms of any given location — all these can provide clues to character that can make someone come alive on the page. In my newest novel, Little Nothing, the village, city, and country are not defined, but the characters exist in specific environments. The main character, Pavla, begins her life in a rural village. Indoor plumbing is a new thing. Her father is the village plumber and she is born a dwarf and so is small enough to crawl beneath homes and help him with his work. Her experience of the underneath, of tunnels and darkness, and her sense of her size in relation to the larger world, become key components to her identity.

KP: Before becoming an author, you worked as a successful screenwriter and film director in Hollywood. What, to you, is the relationship between stories on the screen and stories on the page? How does your experience as a screenwriter inform your prose — if at all?

MS: The differences are many, but one of the most significant is that a novel allows you to dwell in the consciousness of a character by giving language to interiority. Film offers the image, the close-up, and the particular performance of an actor or actress to describe interior feeling, but I would argue that a viewer’s access to unspoken thought is more limited in film than in fiction. The dialogue in film may suggest thought, but seldom does a film allow for a character to have the chance to describe the minute shifts of his or her consciousness. Another significant difference is the way time is treated. By and large, films are linear and move in one direction — forward. For the most part, they do not show the way in which we are continually circling back in our minds and in our memories so that the past is very much a part of the present. Time in fiction is a more elastic element that can more closely address the way in which we really experience the way time is layered and repeated.

KP: Over the past fifteen years, you’ve written four novels and two short story collections. How do you feel you’ve grown as a storyteller between and among these publications? What was the greatest challenge of your most recent novel, Little Nothing?

MS: Unlike my previous work, Little Nothing ventures into the realm of the fantastic. At the same time it is grounded in a recognizable reality. My intentions for the novel were that it reflect recognizable conditions of our lived experience. So the challenge of the novel was to find a way to use the surreal not as a portal to the absolutely unbelievable, but to activate it as a kind of boomerang, so that, as far out of the realm of our known experience the plot ventures, it returns us to something we recognize. In order to do this, I had to make sure that the transitions Pavla goes through, as uncanny as they might appear, were undergirded by a kind of emotional and experiential truth. No, we don’t morph into wolves, but on the other hand, there might be some undeniable part of our natures that we recognize in the wolf Pavla temporarily inhabits.

KP: In previous interviews, you’ve called Little Nothing an “existential fable.” What makes you say this? What does the space of the fable offer — both to the reader and to the writer — that other forms of fiction do not?

MS: This goes back to the previous question. Fables function not because they are patently unrealistic, but because, through the lens of the surreal, they shine a light on something deeply true within the psyche. The story of Pavla and her strange transformations has to do with the way in which we change throughout our lives, in ways big and small, sometimes naturally, through maturation, sometimes unnaturally, because of the pressures of external influence, which can often be violent or negating. The book is very much about the experience of women and their bodies. Pavla’s is stretched and changed and brutalized and hunted. Through it all, she has to continually reconnect with her identity. The more her external physical markers are stripped away, the more she becomes something that is essentially her.

KP: Fables are known for their layers of meaning, challenging readers to navigate the space between the “plot” and the “moral” of the story. What is the relationship between the literal and the symbolic in your prose? Do you tend to privilege one above the other? What would you say to someone who asked you to identify the “moral” of Little Nothing?

MS: When I write, I don’t think about meaning or moral or the overall thematic intentions of the work. I think about story, about characters who are rich and alive, about finding surprising yet inevitable actions. When a piece is finished, it is a reader’s privilege to discover what he or she sees in the work, and those discoveries can be as varied as readers are varied. The old fables may have been written with moral intent (although I don’t think all of them are) but that is not the way I work, even as I used some of the tropes of fable. The idea of a moral implies morality, that a work is teaching us what is “right” and what is “wrong”. I don’t think that fiction should act as moral legislator. Fiction should expose the complexity of life, not reduce it.

KP: The protagonist in Little Nothing, Pavla, endures torture, enslavement, and objectification, surviving by moving between human and non-human forms. Despite these themes of violence, you’ve noted that the novel is, in part, a story about “endurance and transcendence.” When writing, how do you envision the relationship between these emotional extremes — between, for example, the pain of violence and the hopefulness of love? How does Pavla’s liminal identity complicate this relationship?

MS: Life is a big stew. Pain, love, humor, darkness, loneliness, comfort — everything exists in a single breath. So the violence Pavla endures is inextricable from the love she occasionally experiences and the love she engenders. Little Nothing is a kind of love story, but an unusual one, perhaps. Pavla incites love in the young man, Danilo, who then spends the story coming to a realization that love can exist outside its object, that it is something more mystical than tangible. Pavla’s “liminal identity” — a wonderful phrase to describe this — one in which she changes and ultimately transcends the body entirely, allows for this kind of more metaphysical consideration of love.

KP: As a seasoned and prolific author, what advice would you give to young writers, both those who are writing their very first stories and those who are seeking publication?

MS: Writing is a practice. It needs to be attended to diligently if you are to improve. Write a set amount of words each day. Don’t skip a day. Don’t let yourself off the hook because you are tired, or because you don’t feel inspired, or because the blank page is frightening. Just write one word. Then the next, and the next.

KP: What’s next for you?

MS: I’m making my way into the territory of a new novel through reading and research. And I’m writing something each day. Not necessarily something I’ll use or publish. But I’m putting words on the page.

**

Marisa Silver is the author, most recently, of the novel Little Nothing. Her other novels include Mary Coin, a New York Times Bestseller and winner of the Southern California Independent Bookseller’s Award, and an NPR and BBC Best Book of the Year, The God of War, which was a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize for fiction, and No Direction Home. Her first collection of short stories, Babe in Paradise, was named a New York Times Notable Book of the Year and was a Los Angeles Times Best Book of the Year. When her second collection, Alone With You, was published, The New York Times called her “one of California’s most celebrated contemporary writers.” Silver made her fiction debut in The New Yorker when she was featured in their first “Debut Fiction” issue, and many subsequent stories have been published in that magazine. Her fiction has been included in The Best American Short Stories, the O. Henry Prize Stories, as well as other anthologies. She received her MFA from The Warren Wilson MFA Program for Writers. She is a visiting Senior Lecturer at the Otis College Graduate Writing MFA Program and is a member of the fiction faculty at the Warren Wilson MFA Program.

April 27th, 2017 |

Midwestern Gothic staffer Kathleen Janescheck talked with author Jay Baron Nicorvo about his novel The Standard Grand, raising chickens, writing his way to the surface, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Kathleen Janescheck talked with author Jay Baron Nicorvo about his novel The Standard Grand, raising chickens, writing his way to the surface, and more.

Jay will be appearing in Michigan to promote his book next week and the week after! Stop by the following locations to hear him talk about The Standard Grand:

April 26th, Wednesday 7:00 PM at Bookbug in Kalamazoo, MI (details)

May 3rd, Wednesday 7:00 PM at Literati in Ann Arbor, MI (details)

**

Kathleen Janescheck: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Jay Baron Nicorvo: For a few of my earliest years, my family lived in a Chicago suburb while my parents’ marriage collapsed. They’d been together for more than a decade, right out of high school, when they decided to have kids — I’m the oldest of three boys, the Dmitri, you might say, if you’re a Brothers Karamazov fan — as a way to maybe salvage their relationship, or to distract themselves from it. No such luck.

I still have stark memories of my earliest Illinois days: harvesting red clay in the surrounding undeveloped lots; the collective fear of a confirmed child molester trolling through the neighborhood in an old orange Volkswagen, soliciting kids; coming home from an outing with the family next door to find my mom, eight-and-half-months pregnant, unconscious on the floor of her bedroom, phone off the hook beside her. (I’m realizing my father’s in none of these recollections.) I don’t think these experiences are particularly Midwestern; they’re more typically suburban American.

After my youngest brother arrived, my mom moved us back to the Jersey shore, where I’d been born. My mom’s as “Jersey Girl” as they come — the song not the movie, and more the original, raggedy-ass Tom Waits version than the smoldering Bruce Springsteen rendition. Five years later, when she got sick of Jersey once and for all — sick, really, of the gray, rainy winters cooped in a duplex with three feral boys — she and her sister relocated us to Florida so we could run wild in the temperate December sun. I spent the next twenty-five years shuttling up and down the Gulf and East coasts — Sarasota, Boston, St. Petersburg, New York City.

My wife and I — she’s also a writer, Thisbe Nissen — bought our first house in the foothills of the Catskills of New York. Outside a little village called Saugerties a few miles from Woodstock. We lived there for a couple years and commuted insane distances for our city jobs. When we determined to have a child, our situation felt impossible. Thisbe was offered and accepted a full time teaching job at WMU in Kalamazoo, and within days, we conceived our son. After he was born, we relocated to Bedford Township, north of Battle Creek, aka Cereal City. We’ve been in Southwest Michigan for six years now. It’s not without flaw — we’re in the sticks, Trump country, woefully outnumbered and outgunned — but we love our home.

KJ: As a transplant to the region, do you think that the Midwest has seeped into your writing?

JBN: There’s a certain Midwestern sensibility to be found in my writing, to be sure, and I’m hoping that — with the publication of my first novel and the readings I’m doing in the region — some of my writing even seeps into the Midwest. They both tend toward the sincere and the heartfelt, as I understand them. They avoid irony, value intimacy and privacy. They’re hardworking; they’re earthy. There’s an unnamed tension under the surface and, oh yeah, there are guns.

Maybe it’s due to growing up poor on the East Coast and then in the South, raised by a pair of working-class Jersey girls who could both be vividly sarcastic and caustic. (I can look back, fondly, on all the times my mom told me, in all sincerity, to get bent.) But at some point in my early twenties — after my requisite snide adolescence — I became supremely earnest, and earnest I’ve remained. That strikes me as particularly Midwestern.

In person, I can’t really stomach sarcasm. Irony annoys me. I’m repelled by people who mean the opposite of what they say, even in jest. Or don’t take time to consider what they mean. I’m afraid I sound humorless, but I love humor. It’s biting wit that I don’t care for — I suppose I’m witless!

And it occurs to me that I’m really railing against everything our president represents. Trump’s just about as anti-Midwestern as they come. He’s East Coast privilege of the worst sort. Snarky. A particular brand of mean amorality. Self-serving, vindictive, materialistic, cynical and faithless. He’s a douchebag. (Can I say that in a wholesome, albeit gothic, Midwestern journal? Can you see I don’t fully belong to the Midwest?) Our menstruphobe president is a douchebag — it’s worth repeating — who gives douchebags a bad name, and the one thing I hold against Midwesterners — the knock on earnestness — is it makes you an easy mark for hucksters and conmen. A number of you — Michiganders and Ohioans especially — got conned last November, and royally.

But the thing is, when creating characters — and our president is nothing if not a character, a Dickensian Scrooge, flat to a fault — those with attitude steal the show. Same holds true for modern politics, where snark wins votes, and in reality television, where the wrecks increase ratings. In writing dialogue, like in a debate, meanness and wit score points. They create dramatic tension. The mother who shouts at her son, “Get bent!” is far more striking, and compelling, than the mother who says, “Be nice to your brothers.” But I’ve gotten distracted — what was the question again?

KJ: Though you have not personally experienced war, your novel, The Standard Grand, focuses on characters who have. What is your process for writing about things you haven’t experienced?

JBN: No, I have not experienced war, but I’ve experienced trauma and depravation. Phil Klay has a killer essay about some of the parallels. That said, my civilian traumas are not wartime traumas. The differences are exponential. And yet any hardship opens you up to empathy, and empathy, coupled with an abiding interest, can get a writer convincingly into a character. But I don’t believe I have the right to write from any point of view I choose; I believe I must earn that right every time I sit down to write.

My process for this is simple if not easy: read everything. I immerse myself in a subject until I lose myself in it, literally. You’ve got to reach the saturation point where you’re drowning in primary source material. Then you write your way to the surface, and you do that partly by working hard against stereotype. Once you’ve reached the surface, once you’ve polished that surface to a shine and are reasonably sure that beneath the surface lies some significant depth, then seek out a reader who’s experienced what you’ve written about. She’ll call you on your bullshit, and you revise with her opinions in mind.

This is to say that I don’t place much stock in writers who tell you, “Write what you know.” It’s more important, and more interesting, to know what you write. It’s writing as a way to come to know something you didn’t before. I’m striving to make difference feel intimate. If I do that well, maybe I’m able to drag the reader along on a strange, new ride and, on the way, maybe some of our overlooked similarities reveal themselves. We might even end up becoming more than we were when we started out.

KJ: The main character in your novel was inspired by your former sister-in-law. How has working on this novel shaped your thoughts on her?

JBN: Outside of that initial inspiration, which I’ve written about elsewhere, it hasn’t, not really. I try to maintain separation between actual people living lives in the real world from the characters those people might inspire me to write about. There’s always a disconnect in fiction, especially, but even in nonfiction. The “mom” I’ve described above — ostensibly in a truthful way — bears little real-world resemblance to my actual mother, whose complexity, beauty, and humanity far exceed my capacities to capture her in language.

So while writing and reading about my main character taught me loads about women and soldiers, generally, Specialist Smith hasn’t taught me much specifically about my former sister-in-law. For that, I’d have to track her down and reestablish a relationship, which isn’t my place. That would be a violation of my devotion to, and my love for, my brother. Besides, both of them have moved on. They’ve both remarried. Both have children with their new spouses. My brother is far happier, and far better off, and his ex-wife appears to be, too.

KJ: Reality informs fiction. Do you ever find fiction–either writing or reading it–informing reality?

JBN: Sure, all the time, and I wouldn’t write fiction, or read fiction, if it didn’t inform reality. Our best fiction shapes our sense of reality; hell, the best fiction sometimes feels realer than reality. It helps us define and understand the world, the people, and the creatures in it. And we now know fiction, the reading of novels, offers a kind of empathy exercise. For my money, there’s no better way to inform reality.

KJ: You’ve spoken in the past about how the military dehumanizes the enemy, and in turn, leaves soldiers un-empathetic. Has this detail shaped your characterization of Specialist Antebellum Smith?

JBN: Less Specialist Smith than some of the other characters in the novel. Smith maintains a significant capacity for sympathy, and I think that’s partly her emotional undoing. The US military does an incredibly efficient job getting our soldiers ready for conflict. All attention is paid to the front end. We’ve got it down to a science. A good portion of modern combat training is Pavlovian conditioning; the world’s largest employer of psychologists is the U.S. Army Research Bureau. But we do a godawful job on the backend. We do next to no reconditioning when our soldiers come home. We’ve got to get better at re-humanizing, and my novel, in an astoundingly inefficient and obscure way, tries to offer some means that we might, as a nation, go about helping soldiers de-escalate conflict. But very specifically, and cost effectively, we can help to re-ready vets for civilian life by getting them to exercise their empathy muscles. Vets should read more novels. We all should.

KJ: Your characters are often either receiving or dispensing violence. What makes you want to write about violence?

JBN: Well here, I suppose, is one way a writer can’t escape writing what he knows. I had a violent upbringing. My mom was as loving and as affectionate as could be, but she wasn’t protective. Partly, she was parenting according to the uniformed times — more lead in the gasoline! dumb down a whole nation! to hell with the seat belts! — but mostly she was working seven days a week at a 7-11. She often wasn’t around to keep the wolves in the woods. And her second husband, come to find, was lupine, and a lunatic. But, make no mistake, I don’t want to write about violence. My writing involves the poor, and poverty — in my experience in our country in this day and age — breeds violence.

KJ: What has running a small farm taught you about writing?

JBN: Defunct farm is more like it. We grow a garden, and we have a couple dozen chickens at any one time. But we don’t run a farm; our farm was long ago overrun! I will say, though, that my most influential writing teacher, Sterling Watson, was a fan of the Southern Agrarians (sometimes called the Fugitive Agrarians), Robert Penn Warren and John Crowe Ransom among them — O, the patriarchal pretension of all the sad lettered men placing small bets on the name trifecta! — and Sterling talked often about needing to let the land lie fallow for a time after working it hard. Otherwise, you sap it of all nutrients and it won’t produce. I hold fast to that metaphor during my downtime, when I’m struggling for days to steer the walk-behind tiller, or splitting and stacking firewood for weeks, or wrestling our old tractor to a bloody-knuckle draw, or helping to raise an organic six-year-old child.

KJ: Which of your chickens is your favorite?

JBN: Good parent that I try to be, I play no favorites, but sometimes I can’t help myself. And each of our hens is her own person. They all have names, and if someone ever tells you chickens are stupid, that person’s an idiot. People are stupid. Or, people are so closed-minded and obtuse as to render themselves stupid.

To overcome our stupidity — the human bias in our pattern recognition; we can’t see the chicken for the brood — Thisbe and I won’t raise two chickens of the same breed. This way, we can tell them all apart. If you can tell them apart, you can overcome the idiocy of your prejudice. You have an easier time seeing them as individual and you’re able to observe, appreciate, and understand each chicken, who’s got her own attitude and sentience, make no mistake. This is another brand of empathy exercise. It’s also speaks to building character — both in fiction and in ourselves.

Of our newest brood, all year-old hens, there’s one who, from two-days old, was very interested and invested in us. We named her Punny Chunny Conghi, after a figurine dubbed by our son, Sonne. We kept a list of his toddler’s names for things and neologisms, and that’s one place we draw names for our chickens. There’s O’mahdee, Sonne’s mishearing of “Molly-O,” the Steve Earle song; Old Bang Bones, something Sonne called his favorite washable marker; and Huggeen, Sonne’s name for a carrot he was especially fond of.

But Punny Chun. When she was in the horse trough in the dining room with the other chicks, we’d peek our faces over the lip. She was always the first to make eye contact — usually with her left eye, which may be her dominant — and she kept that watchful orange eye trained on us. She was eager for handouts and unafraid. We handle them a lot when young, and I’ve taught them to come when called. Punny Chun, who’s a Dorking, a breed believed to date back to the Roman Empire, has these pink five-toed feet at the end of squat little legs. She looks like a big dove, coos like a dove, and is loving as a dog. She follows us around to be picked up and petted, but don’t mess with her. She is, after all, a little dinosaur, and she’s already worked her way toward the top of pecking order. She lords it over most of the other hens, even our mean menopausal eight-year-old, Bluebeard.

KJ: In reviews, your work has been likened to Delillo, Pynchon, and others. Do you consider any of these authors to be an influence?

JBN: Yes.

KJ: What’s next for you?

JBN: Backgrounded by my window on the Midwest are some of the key ingredients. I’m refining the recipe, making a terrible mess in the kitchen, and hopefully someday it’ll yield something palatable.

**

Jay Baron Nicorvo is the author of a novel, The Standard Grand (St. Martin’s Press, 2017), and a poetry collection, Deadbeat (Four Way Books, 2012). He lives on an old farm outside Battle Creek, Michigan, with his wife, Thisbe Nissen, their son, and a couple dozen vulnerable chickens. Find Jay at www.nicorvo.net.

April 25th, 2017 |

Midwestern Gothic staffer Audrey Meyers talks with author Brian Volck about his book Attending Others, finding beauty in the ordinary, juggling a career in medicine with one in writing, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Audrey Meyers talks with author Brian Volck about his book Attending Others, finding beauty in the ordinary, juggling a career in medicine with one in writing, and more.

**

Audrey Meyers: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Brian Volck: The Midwest is my home, or was until very recently. I was born in Cincinnati, left for St. Louis to attend college and medical school, and did my pediatric residency in Cleveland. After residency, my wife and I lived and worked for five years in Tuba City, Arizona, a town on the Navajo Reservation. We loved the work, the people, and the place, but we also wanted our kids to see their grandparents more than once a year. That’s why we eventually moved back to Cincinnati. That was a real homecoming: our Cincinnati house was less than two miles from the hospital where I was born. We stayed put for twenty years, but life takes strange turns. We currently live in Baltimore, Maryland, because of my wife’s job and to be near my aging in-laws. Family trumps place once again. Well, not entirely. All three of our children still live in Cincinnati, and I return often to work at the Children’s Hospital, visit family and friends, and attend writing-related events.

Living in Baltimore and still working, however irregularly, in Cincinnati makes for a complicated life. I also return often to the Southwest to work on Native American child health issues. For now, however, Maryland is my current physical home, the Southwestern desert is the landscape of my heart, and the Midwest is my true homeland.

AM: You’ve spent a lot of time with diverse communities from all over the country, what aspects/values of the Midwest do you carry with you to these places?

BV: I like to think I carry a Midwestern ordinariness with me. I have a bad habit of taking myself too seriously, so it helps to remember the plainness of my origins. There are more powerful and cosmopolitan cities, more astonishing and beautiful landscapes, more eventful and consequential histories to be found elsewhere. But that’s not all bad. It gives Midwesterners a sense of place, however apologetic we may be about it. We have to look harder to find beauty or worldly consequence in what others call “flyover country.” In a land of moderate terrain, second-growth forests, and cultivated fields, or where bland, lookalike suburbs sprawl from aging cities, one either develops a practice of attention or fails to see the subtler beauties and quiet suffering around them.

Karin Bergquist and Linford Detweiler, the couple who make up the band Over the Rhine, moved some years ago from Cincinnati to a farm in Highland County, Ohio. The songs that have grown out of that experience name the beauty and suffering lurking in the ordinary: clouds at sunset, a tupelo tree set against the ironweed, scarred mountainsides, stray dogs on an urban street. Karin and Linford are lifelong Midwesterners who pay attention to the ordinary and find it wonderful. I try to carry some of that with me wherever I go: rural Honduras, a hospital room, a barren hillside on the Navajo Nation.

There are, to be sure, other ways of understanding Midwestern ordinariness. To other regions in the US, our part of the world looks rather homogeneous, and it’s easy to misconstrue the Midwestern “ordinary” as grim demographic uniformity. Some of that talk resurfaced in the wake of the recent presidential election. There are parts of the Midwest where that may well be true, but there’s nothing uniquely Midwestern about that. And if change comes more slowly to the heartland than the coasts, change has always been coming.

In Attending Others, I explore several lessons I learned growing up in an all-white suburb. Some of those lessons needed to be unlearned. I hope attentive readers can see that happening in my encounters with people whose circumstances are very different: an African-American boy in Cleveland, a Navajo girl, children in rural Honduras. This unlearning may take a lifetime, but I can see things changing in something as simple as a family photo: my daughter was born in Guatemala, my sister in law’s grandparents came from China, and my sister’s children are Indian-American. The suburb I grew up in is no longer exclusively white. I hear languages spoken at the Children’s Hospital that my younger self didn’t know existed. The ordinary is, as always, being redefined.

AM: How has the Midwest impacted your extensive list of passions, from teaching medicine to advocating for children and families in poverty?

BV: That’s an interesting question. While the Midwest didn’t create my passions, it certainly shaped them. I come from a family riddled with visual artists, musicians, and even a few medical professionals. I grew up in a house full of books. Though my father was in business, he sang in various choirs and taught night courses at a local university. My mother also sang, played piano and organ, and was a grade school teacher. They showed – rather than told – me not to limit my interests and goals to one part of life.

I’ve had many wonderful teachers whose passion for their subject made me passionate as well. To riff on Mark Twain, the difference between a great teacher and an adequate one is the difference between lightning and a lightning bug. Many of those teachers, especially in college, medical school, and residency, were committed to working with and for families – and especially children – in poverty. Our shared interests drew me to them.

Many had a Midwestern sensibility. They never imagined they would save or transform the entire world, but they saw a particular need and responded to it with all the effort and resources they could bring. Some traveled to developing countries. Others worked in the inner city. All remained rooted to the place they still called home. Fidelity outweighed flashiness or fame. It’s not that they were doing unimportant things. Their motivation came less from personal ambition than from a sense of right action. I like to think of my time with them as an apprenticeship, watching how they worked, trying to the best of my ability to do the same. I hope to never forget where I come from, the privileges I have, and the mentors who showed me how to engage the world from a particular place.

AM: How has your profession as a doctor influenced your work as an author? In other words, how does medicine and writing coincide in your life?

BV: It turns out that medicine and writing are both jealous lovers. Each demands a lot of undivided attention and lets you know when they’re not getting it. I wanted to be a doctor and a writer for as long as I can remember, and I had examples of doctors who pulled the thing off: William Carlos Williams, Robert Coles, Richard Selzer, and Lewis Thomas. Today, I’d add Abraham Verghese, Atul Gawande, and the late Oliver Sacks. They made the combination look easy. Maybe it is for them.

For me, medicine is the easier of the two. I do what I’ve learned from long years of training and watch as my patient gets better – or not. I can reassess, rethink, and adjust my diagnosis and therapy in so-called “real time.” Doctors often hear a small voice of self-doubt after a patient they encounter, a lingering worry they may have overlooked something important, that they should have done something more. When doctors lose that entirely, they grow cocky, dangerous. Lives are, after all, in the balance, and if I miss something important, however hidden it may have been, I feel personally responsible. There’s no certainty in medicine except for the final diagnosis, the one everyone gets in the end. A lingering uncertainty – calibrated somewhere between frisson and paralyzing dread – keeps me focused on the patient, makes me return to the basics of history taking and physical exams.

There’s a similar uncertainty, frequently bordering on dread, in staring at the blank page. I tell myself to just put words down, one after another, that I’ll revise later. Each new writing project brings its own little voice, saying “You don’t know how to do this.” The truth is, you don’t, but you go ahead and do it anyway. And if you’re determined enough to write, revise as many times as necessary, and find it sufficiently crafted to share, there remains the uncertainty of how your work will be received. When I publish something, it’s like sending a child out into the world. I want my babies to be loved, but it will be awhile before I know if anyone even notices, much less likes them. All that’s beyond my control. For too long, I let the short-term rewards of medicine outweigh the uncertain outcome of writing. I needed to write, but I had to overcome my fear of failure. It still takes longer to finish writing anything – short or long – than I’d like, but I’ve learned how to distract the inner critic long enough to get words, however inadequate, on the page.

That said, there are deep similarities in the practices of medicine and writing. Doctors listen to a patient’s story, from which they fashion yet another story: the “history and physical.” Good clinicians and writers attend to the telling detail: the tremor in a lip or hand, the stain on a sleeve, the uncomfortable silence between a question and its answer. The best in both professions look for the story beneath the story: not just a diagnosis, but the measure of the person before you, not just a narrative, but an insight into the human experience. Maybe that’s why there are so many doctor-writers, despite all the difficulties.

AM: Your book includes the experiences of your patients and your own personal experiences. In regards to ethics, do you find yourself struggling between these two aspects? Is it difficult being a doctor and writer in order to write personally about your professional life? How do you decide on what to include and leave out from your experiences?

BV: If I understand your question, you’re getting at one of the most contested matters in creative nonfiction: what particulars must go into a nonfiction piece and what should be left out, whether out of propriety, compassion, or fear of litigation. Sharing doctor-patient stories complicates matters. First of all, there’s HIPAA, the federal law that appropriately restricts the sharing of personal health information. That’s not really a problem, as I change the names of patients and family members or alter personal details to protect their privacy. If I write at length about a particular patient, I let the family read and comment on it before making anything public.

Second, there’s the necessity for confidentiality and trust between doctor and patient, given the intimate nature of the relationship. Patients tell me things they haven’t shared with their parents, spouses, pastors, or therapists. Third, there’s the need to respect the dignity of others, including their custody over their own stories. Anne Lamott says something like, “You own everything that happened to you. Tell your stories,” but that’s not really true for doctors. I don’t own my patients’ stories, yet they are an essential part of my life.

In Attending Others, it’s precisely those stories that I wanted to share with the reader: stories about what comes from paying attention – “attending to” – patients and families whose lives are noting like mine, who are distinctly “other.” As a physician, I’m privileged to enter those stories, to discover where that otherness can be bridged and sometimes where it can’t. Early in the book, I quote the philosopher, Emmanuel Levinas, as saying, “The encounter with the Other calls the self into being.” I learned a great deal about Navajo and Hopi culture in the five years we lived on the Navajo nation. I learned far more about myself, the most important lesson being “I’m not Indian.” In realizing that, I felt compelled to find out who I was, where I came from, what inherited habits and assumptions I took for granted. I hope that ongoing search opens me up to richer encounters with otherness, though I leave it to the reader to decide if I’ve made any headway.

Here’s how I see the challenge. I write my story by showing the reader what I experienced, thought, felt, and did with as much sensory specificity as possible. I also share telling details of my patients to the degree the story demands. To do less is to deprive them of their human complexity. The goal is to make the experience, including my experience of the patient, available without stripping away anyone’s dignity. I hope I come down in that narrow swath of narrative territory where the demands of the story and the dignity of the person overlap.

AM: Who do you write for?

BV: I hope Attending Others is accessible to a broad public, from health care professionals to fans of memoir, but I rarely start anything with a readership is mind. Obvious exceptions would be pieces written at someone else’s request, whether for a specific occasion or periodical. Most of the time, I write because I’m conscious of words or experiences that won’t let me go until I write them. In the past, when fear of failure outweighed my need to write, I let words wither and die, unwritten and mostly forgotten, though they went on haunting me. Unwritten stories, essays, and poems linger in memory and desire, like roads not taken.

When I sit down to write, I hope to discover something I didn’t yet know how to say. If I knew exactly what I was going to say before putting the words on the page, I’m not sure I’d do it. Even if I have the last sentence of a poem or story in mind, I still need to find a way to get there, and in improvising that path, the conclusion itself may change. If I don’t discover something in the writing, why should I expect the reader to do better?

Yet it helps immensely to have someone to whom my writing is accountable, someone to say, “Where’s the work you promised me?” It’s not as though the world would notice something missing if I’d never published a word, but an editor or mentor will. The earliest-written section of Attending Others came some years ago at the request of Robert Coles for the late, great magazine, DoubleTake. A significantly revised version of that essay became the chapter on paying attention. The remaining skeleton of the memoir grew during my MFA. Once I found a publisher, I fleshed out that skeleton with more chapters. Each addition changed the story as a whole, leaving chapters I thought finished in need of revision. With each step, the story grew clearer, like a figure emerging from a slab of marble beneath the sculptor’s chisel. No one ever mistakes someone as clumsy as me for a sculptor, but I’ll stick with the analogy. The surprise was in discovering the real story hidden in the mess of words.

AM: What inspired you to write Attending Others? And what gave the book a sense of purpose for you?

BV: Inspiration isn’t the right word. It was more a matter of awareness, of recognizing the as yet unfinished book forming out of the independently conceived pieces I wrote in the course of my MFA. I didn’t start with a book in mind, but as an MFA student in creative nonfiction, I hoped to find a narrative arc in the episodes from my life rendered on the page. I had previously resisted writing about my life as a doctor – it almost never shows up in my poetry – but once I started, the stories kept coming.

As stories accumulated, I glimpsed a unity I hadn’t seen before: my most important lessons about medicine came after my formal education. More often than not, they came from non-professionals: patients, mothers, grandparents. Once I saw the story beneath the individual stories, the sense of purpose followed. I realized the enormity of my debt to my patients, my family, my mentors, and the students and residents I teach. Children – my own and my many patients – remain my best and most humbling teachers. Maybe that’s true for every medical professional’s relationship with patients, regardless of age, but I’m at my best with kids, mostly because they accept you as you are and can detect phoniness in seconds. Their lack of pretension, their transparent motives and desires helped me see what I was doing as a physician. Those essential practices of history-taking and physical exam I learned in medical school and honed in residency are practices of attentive presence. They were calling me to a heightened attention, not just to the making the diagnosis and prescribing therapy, but to the complex wholeness of the person in front of me.

There were further discoveries as I wrote that kept me going. The final two chapters came after I imagined the book had reached a conclusion. I realized rather late that I was wrong. The story hadn’t even reached a stopping place. True stories about living people can reach a stopping place, but that’s not the same as reaching a conclusion. As life goes on, the past continues to be reinterpreted through the lens of lived experience. Stories, though, need a stopping place, however tentative. The best stopping places also feel like starting places, the story’s momentum not fully spent. Those two final chapters were necessary, but they left the whole book feeling bloated. In the end, I ripped out 18,000 words from the original manuscript, anything that didn’t serve the story. The result, I hope, is a better, leaner book where what words remain don’t take up space, that they truly count.

AM: Which writer most influenced your style? Or even broader since you work within a multitude of disciplines, who has most influenced your writing style?

BV: The list is long, but the most important influence on my writing as a whole is Wendell Berry, though that may be visible to no one but me. I desire his clarity. I covet his mastery of the natural cadence. I want to stand by my words as resolutely as he stands by his. I envy those clean sentences that prove amiable and challenging at the same time. He’s just like that in real life. There are no visible seams between the way he lives and the way he writes. Other prose influences include Tobias Wolff and Ernest Hemmingway, who showed me the power of short, declarative sentences, and Annie Dillard, who renders complexities in accessible language and reveals the mystery hidden in the mundane.

Poetic influences include Wendell Berry again, and Scott Cairns, who writes in a rather different style, though both render the body in ways I find instructive. B H Fairchild showed me how to tell stories in contemporary poetic form. Howard Nemerov and Emily Dickinson are my exemplars for knotty, gnomic lines engaging immensities. Then there’s Mary Oliver, whom I can’t read often enough. I also draw inspiration from the lyrics of poetic singer-songwriters such as Joni Mitchell, John Gorka, Karin Bergquist and Linford Detweiler of Over the Rhine, and Joe Henry.

AM: What’s one thing you wished you’d known when you first began writing?

BV: That writing is learned by writing, period. The learning is in the doing. Mentors and books on writing provide some helpful tips, but books don’t set deadlines. Mentors do. I’m indebted to my mentors for the nuts and bolts critiques they provided, but their greatest gift lay in their expectations. They wanted the best I could do and they wanted it on time.

The poem, essay, or story in my head is always better than what ends up on the page, where I can see all the joints and seams, the flaws and holes I never fixed to my satisfaction. Yet what’s on the page, unlike the story in my head, exists. It can be read by another person. However perfect the imagined work seems, it doesn’t exist until it’s at least spoken (if it’s short) or written. Waiting for my writing ability to catch up with the story I want to tell is like waiting for a rowboat to grow an outboard motor. Use what you have. Read a lot. If you’re fortunate, someone will show you how to row more efficiently, but you’ll still have to row if you want to get anywhere.

AM: What’s next for you?

BV: With Attending Others published, I’m out of excuses not to write the book I’ve been researching for the past seven years. I hint at it in the last chapter of the memoir. Some of the Navajo children I was privileged to care for had conditions unusually common or unique to the western half of the Navajo Nation. The reasons for this geographical concentration include historical events 150 years ago: the Navajo Long Walk, which has similarities to the better-known Cherokee Trail of Tears. I’m trying to tell the story of the families I know, the doctors, nurses, and researchers who cared for them, and the culture and history behind the Long Walk and events since. I’ve written some of that story, but there’s much to do before the book exists. So you needn’t worry about me. There’s enough to keep me busy and out of trouble for a long time.

**

Brian Volck is a pediatrician who received his undergraduate degree in English Literature and his MD from Washington University in St. Louis and his MFA in creative writing from Seattle Pacific University. He is the author of a poetry collection, Flesh Becomes Word, and a memoir, Attending Others: A Doctor’s Education in Bodies and Words. His essays, poetry, and reviews have appeared in The Christian Century, DoubleTake, Health Affairs, and IMAGE.

April 20th, 2017 |

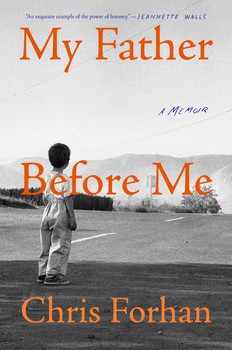

Midwestern Gothic staffer Megan Valley talked with author Chris Forhan about his memoir My Father Before Me, opening oneself up to language and its possibilities, not finding all of the answers and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Megan Valley talked with author Chris Forhan about his memoir My Father Before Me, opening oneself up to language and its possibilities, not finding all of the answers and more.

**

Megan Valley: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Chris Forhan: I have lived here since 2007, when I took a job teaching at Butler University in Indianapolis. Before that, I lived in almost every section of the nation—the northwest, northeast, southeast, deep south, southwest—except the vast middle. However, I have some ancient roots here. In researching my genealogy as part of my memoir project, I discovered that my great great grandfather—the original Forhan who emigrated from Ireland in the 1850s—spent a few years in Ontario and then settled in Litchfield, Illinois, where he did railroad work. Then he moved fifty miles south to East St. Louis and worked as a railroad laborer there.

Other branches of my family, on both my mother’s and my father’s side, are from Missouri and Minnesota, so, although I was born and raised in Seattle, I am in important ways a product of middle America. After spending decades in the south, I moved to Indianapolis and immediately — oddly — felt at home.

MV: Prior to My Father Before Me, a memoir, you had published several books of poetry. How did you approach the two types of writing differently? Similarly?

CF: When I write a poem, I begin with no intention other than to open myself to language and its possibilities. I resist for as long as possible the temptation to decide what I am writing about. (I learned long ago that reaching such a conclusion too early can kill a poem in its tracks.)

With the memoir, I began with clearly defined questions that rose up in me and nagged at me in such a way that I knew I had to pursue them and that I could do so only in prose: What kind of person was my father, exactly? What led him to the point that, at forty-four, he could decide to take his own life, even though he was leaving behind a wife and eight children? Who were his parents, and who were their parents? What was his childhood like, and how might that have contributed to making him the man he became? In order to answer these questions, I needed to do research: to interview my mother and anyone I could track down who might have known my father, to scour census records and newspaper databases, to study at old photos. Although the memoir is ultimately an act of the imagination in that I had to shape the story and reenact events or speculate about them, the project began with me collecting material and analyzing it. For me, poems inhabit emotional or psychological spaces and gesture toward mysteries that cannot be fully comprehended. In the memoir, I didn’t want to do that. As much as possible, I wanted to discover facts about my father and piece them together in order to piece him back together.

So the two kinds of writing are, at least at their outset, very different from each other. However, as I kept working on the material for the memoir, moving from researching to outlining to writing sentences and paragraphs, I felt the experience of writing creative nonfiction was very similar to the experience of writing poems. In both cases, I find myself lost—usually happily—in a tangle of words and moods and ideas, struggling to shape a phrase or find exactly the right image or massage the music of a sentence—its cadences and vowels and consonants—so that it works just right. Poetry, in its use of diction, image, sound, rhythm, syntax, and the line, dramatizes internal experience; it enacts what it feels like to be human. With the memoir, I was working on a larger canvas, but, word by word, I felt myself confronting the same challenge: to make the language not merely communicate information but physically embody a thought or feeling.

MV: Your father’s life and death are present in your poetry. What made you decide to dig deeper and publish a memoir?

CF: Probably my previous answer addresses this. For my own peace of mind, I hoped to unravel the mystery of my father once and for all, at least to the degree that such a thing was possible. In poems, I had investigated what it felt like to be his son. I have always written in order to ground myself, to feel connected to what is essential, so I knew that I needed to continue writing about my father, but it seemed that prose—with its natural capacity to operate narratively and discursively—was the only form that would work.

MV: How has Catholicism shaped your life and writing, both before and after the death of your father?

CF: In an important way, my life has been defined by my early rejection of Catholicism, the faith in which I was raised. I rejected it not in favor of another religious tradition but in favor of an experience of incomprehensible mystery unattached to theological dogma. I write about this in the memoir. Even if I had not been raised in a religious household, I might very well still have become a poet and still have developed something close to the sensibility I have. However, I suspect that my early struggle to pursue my own nascent personal metaphysics without shame or an impulse to conceal my thoughts was fuel for something fundamental in me: an ongoing fierce desire to defend the private imagination against any force—including coerced religious indoctrination—that would insult its dignity and inhibit its power to bring joy and meaningful order and wonder to a person’s life.

Much of the writing I was doing in my twenties and thirties, I realize now, was in response to having gone through this struggle—with having been brought up with the assumption that I would adopt certain beliefs about divinity and the human soul because they were the custom of the tribe. Few things make me more furious than witnessing someone, merely because of his own subjective notions about God, limiting another person’s liberties. I can get into an intense fit of indignation. Real high dudgeon.

Still, the symbols and rituals of Catholicism—the manger and sheep and chalice and host and crown of thorns and nailed palms and empty tomb—are deeply compelling, in the way a richly-textured dream is. My imagination was steeped in those images and structures, so I often find them informing the structures of my poetry: the shapes taken by my imaginings and rhetoric.

MV: How did you go about doing research for your memoir? Were you concerned about interviewing your mother?

CF: One thing that was important for me from the beginning was to be open with my family — my mother and siblings — about what I was doing and why. I hoped for their blessing, even their help. Each of them agreed to be interviewed, and those talks, especially with my mother, were essential to my ability to piece together a narrative of my father’s life and of our life with him.

I was concerned about interviewing my mother. She is a dignified and discreet woman, and many of the years she spent with my father were difficult ones. I knew that she would not enjoy revisiting them. Still, I hoped that she would feel some of the necessity of this project that I felt, and I think she did feel that — or at least she respected my own feelings about it. She is a very smart and loving woman, and I sensed that intelligence and love strongly as she shared her story, very candidly, with me. It wasn’t easy for her, and seeing the book published — and seeing her name, in the newspaper, attached to its publication — wasn’t easy for her, either. I owe her a lot.

The other research was deliriously enjoyable because I was learning things I had hungered to know for decades. I interviewed whomever I could find who might be related to my father or might have known him, and I looked wherever I could for information, such as census records, newspaper databases, and a trove of photos and other documents about my ancestors that I was given by relatives I hadn’t heard of before I started investigating. I visited cemeteries and traveled to East St. Louis and Litchfield, Illinois, to try to get a sense of where the original Irish immigrant Forhans lived in the 19th century. I was fueled by a kind of reckless curiosity that was rewarded over and over again. It was invigorating.

MV: How has teaching in Indianapolis influenced how you approach your own writing?

CF: There hasn’t been a noticeable influence. I still approach writing as I always have: indirectly. I pluck a phrase or image or rhythm from the air, jot it down, then see if anything happens. I follow the scent of the language into the woods, where, if I’m lucky, I’ll find a poem.

I can nonetheless say that living here has altered, if slightly, the content of my writing. I lived for many years in places—all in the south—that, no matter their eccentric charms, made me feel alienated and alone. My poems often showed that; their energy was the energy of an imagination gasping for air. Indiana is a red state — it voted overwhelmingly, joyfully, terrifyingly for Trump. Still, I live in a little spot of blue within the state and generally don’t feel encircled by strangers, so those desperate feelings don’t show up in my poems as much anymore.

With these new dark days that are upon us all, that may very well change.

MV: You’ve said in a past interview that you were trying to figure out who your father was and what that meant for you, being his son. After writing My Father Before Me, do you feel as though you found the answer to those questions?

CF: I haven’t found all of the answers, but that’s because my father took most of them into the grave with him. Still, I feel much closer to knowing what it might have felt like to be him. Early in the writing, and more intensely as the writing progressed, I felt that the central subject of the memoir was silence: both its power to nurture and heal and its power to distance us from each other and from ourselves. I think there are important things that my father kept to himself and would have benefited by expressing and grappling with, however difficult that might have been. As his son, I live with this legacy, and I try not to allow my natural inclination to turn inward and go quiet to be used as a means of escape, not discovery.

MV: What’s next for you?

CF: Glory and riches.

Oh, just the next poem, and the next, and the next (“the next handhold out of the pit,” as my old teacher Charles Wright once said).

I have put together a collection of poems, half of which were written quite long ago — before the writing of the memoir — and half of which were written more recently. I hope it will find a publisher.

I am sometimes asked whether I have another nonfiction book in me. I don’t know. Writing the memoir was rewarding but exhausting; I wrote it in the first place because I felt I had to — I had no choice. Before I decide to embark on another such giant project, I’m waiting to feel that sense of necessity again.

**

Chris Forhan is the author of the memoir My Father Before Me as well as three books of poetry: Black Leapt In, winner of the Barrow Street Press Poetry Prize; The Actual Moon, The Actual Stars, winner of the Morse Poetry Prize and a Washington State Book Award; and Forgive Us Our Happiness, winner of the Bakeless Prize. He is also the author of three chapbooks, Ransack and Dance, x, and Crumbs of Bread, and his poems have appeared in Poetry, The Paris Review, Ploughshares, New England Review, Parnassus, Georgia Review, Field, and other magazines, as well as in The Best American Poetry. He has won a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship and two Pushcart Prizes, has earned a “Discover Great New Writers” selection from Barnes and Noble, and has been a resident at Yaddo and a fellow at Bread Loaf. He was born and raised in Seattle and lives with his wife, the poet Alessandra Lynch, and their two sons, Milo and Oliver, in Indianapolis, where he teaches at Butler University. For more: www.chrisforhan.com.

April 13th, 2017 |

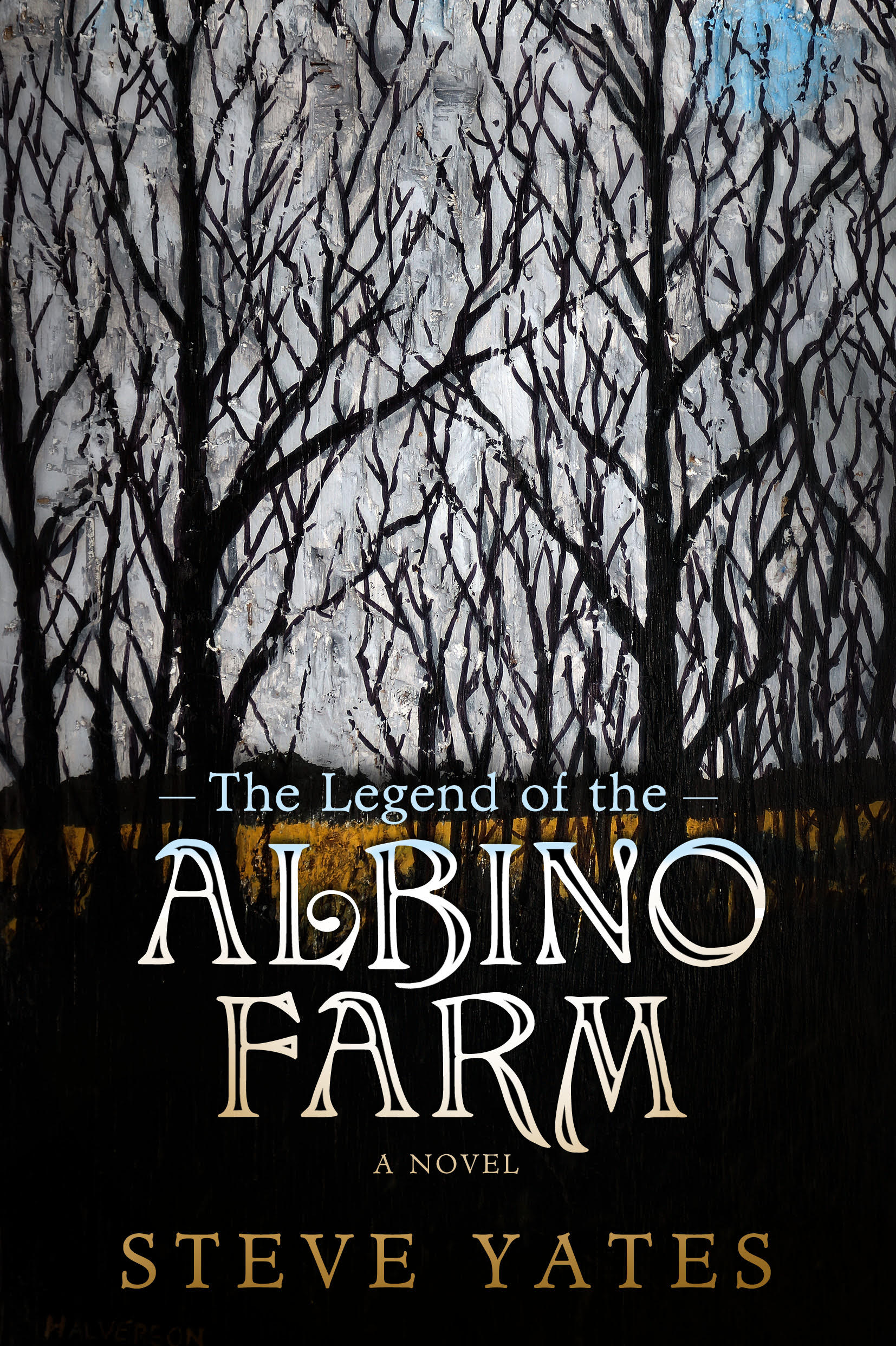

Midwestern Gothic staffer Audrey Meyers talked with author Steve Yates about his book The Legend of the Albino Farm, the dangerous implications of legend, telling a horror story inside-out, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Audrey Meyers talked with author Steve Yates about his book The Legend of the Albino Farm, the dangerous implications of legend, telling a horror story inside-out, and more.

**

Audrey Meyers: What is your connection to the Midwest?

Steve Yates: I was born and reared in Springfield in the Missouri Ozarks, that hilly borderland between the Midwest and the Upland South. Two counties separate my hometown from the Arkansas line. It is the largest city and chief mercantile hub of the region. On a high plateau before the White River Hills begin, Springfield has long been the last market crossroads where provisions from Chicago, St. Louis, and Kansas City could be found. South of town the adventurer descends into a wilderness as oaken and beautiful as it is flinty and perilous. Springfield, Queen City of the Ozarks, lit the stage for Porter Wagoner and gave Bob Barker his start in radio. While with us, Brad Pitt learned to fire pistols and play tennis. We educated the mighty John Goodman and the luscious Kathleen Turner. We are the genius homogenizers who gave you Bass Pro Shops, O’Reilly Automotive, and the first Sam’s Club. You don’t know us, but we sell you everything.

AM: How has the Midwest influenced your writing?