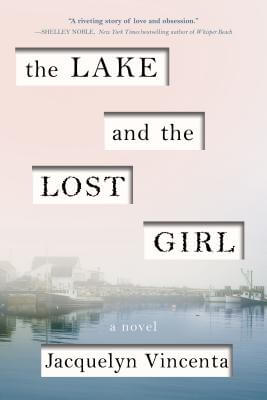

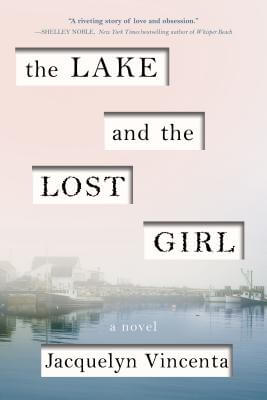

Midwestern Gothic staffer Kathleen Janeschek talked with author Jacquelyn Vincenta about her book The Lake and the Lost Girl, the intimacy of poetry, piecing together a mystery, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Kathleen Janeschek talked with author Jacquelyn Vincenta about her book The Lake and the Lost Girl, the intimacy of poetry, piecing together a mystery, and more.

**

Kathleen Janeschek: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Jacquelyn Vincenta: I grew up in a suburb of Washington, D.C., and left for college in Iowa City without ever having visited the Midwest beyond Ohio. As I crossed the Mississippi River into Iowa for the first time, I unexpectedly felt like I was coming home, and I loved every aspect of my years there. After college I lived in Louisiana, Texas, Virginia, back in Maryland for a time, and then sought out the Midwest again, this time the Great Lakes area. Michigan’s west coast completely captured my heart and I have lived within an hour of it for over half my life now.

KJ: You’ve lived in a variety of places over the years—what drew you to settle in the Midwest?

JV: The balance of water, agricultural land, wilderness, orchards, open space, and interesting human communities was enchanting to me from the start, and continues to holds me here. It’s inconceivable to me now to think of leaving this place, and when I spend any time in areas where the human presence overwhelms my ability to feel close to the natural world, I miss my home in the Midwest deeply.

KJ: Lake Michigan features heavily in your novel, The Lake and the Lost Girl. How does the lake function as a force in both your fiction and your life?

JV: In The Lake and the Lost Girl Lake Michigan is a force of both danger and possibility, providing Mary Stone Walker with companionship, hope, inspiration, and challenge, while it also beckons her toward a different future. The boatbuilder, Jack Kenilworth, thrives on the joy the lake brings him on a daily basis, and he is linked by it to his father and grandfather, in a lineage of men who relied on the Lake for sustenance. My teenage character, Nicholas, goes there for artistic inspiration and relief from the tension of his family. The Lake draws and holds people, yet always remains a force larger and more mysterious than we can fathom, thus it provides balance for our nervous systems and represents the unknowable aspects of life. As I answer this question, I am also struck by the transformative effect of the way the lake reveals light to us. In my own life the lake and its variations of light are one of Lake Michigan’s most deeply moving aspects. The fact that it’s hard to explain how this works inside us illustrates how the lake functions in my life: It connects me to aspects of myself I might not experience without it.

KJ: A family in crisis is at the heart of this narrative. How does your own family life influence your writing?

JV: The family in crisis at the heart of the novel is also the potent seed that generated a full-length narrative. I experienced a family dynamic with some shared characteristics: denial of realities, unreasonable hope that unhealthy relationships would just heal themselves, and emotional and physical violence that caused constant undercurrents of fear and self-doubt among the non-violent members. I wasn’t sure I would be able to write “accurately” about it, portraying the types of problematic family exchanges that I have witnessed and been part of, but in fact the scenes unfolded with the fluency of something long memorized.

KJ: Your story features not one, but two fictional writers. Did you encounter any difficulties when writing two different narratives about writing?

JV: Now that you mention it, no, I didn’t encounter any difficulties with this. I wonder if that’s because writing is something that I imagine to be a natural part of everyone’s relationship with the world, an extension of their internal and external dialogue with life. Writing is not a part of every person’s life, of course, but self-development and self-expression are. But distinctly different for each person, from the way they see to the way they feel about their medium.

KJ: Furthermore, it is Mary Stone Walker, the poet, that the story revolves around. What made you want to write about a poet and not a novelist like yourself?

JV: I admire poets and many of their works resonate like timeless songs through our literary inheritance. There is something so intimate and romantic (sometimes negatively so) about the way the poet sees the world and the unique and fleeting glimmers of it that she reflects back to others, across time. I suspect that if one were inclined toward falling in love with a dead writer and developing an obsessive fantasy about her—as Professor Frank Carroll was—it might be easier if she were a poet than a novelist, partly because you could imagine that lyrical intimacy shared with the absent poet. From a novelistic point of view, it is an important part of the plot that she left fragments of poetry behind, hiding lines and verses that were found years later, and hidden fragments of poetry make more sense and are potentially more beautiful than small bits of prose.

KJ: What do you think is the most important element in crafting a mystery?

JV: I am still learning the answer to this question. But it seems to me that one of the most essential and yet most difficult elements in crafting a compelling mystery is to bring the secrets at play within the story as close to the surface as possible without anyone fully understanding them for what they are until the end. When these motivating, disruptive energies are present but not revealed they should give rise to words, behavior, and intriguing events that drive the story logically forward, even without the full truth of them being available to the reader… and yet we feel them there so that when the facts are all made clear, they resonate back through the tale. One of the deepest pleasures of reading a mystery is that experience, as you complete it, of reviewing the tale with newly enlightened eyes.

KJ: Each chapter of your novel, The Lake and the Lost Girl, features a few lines of verse from various poets. How did you choose these lines?

JV: The quest for lines of poetry by American female poets of the same era in which fictional Mary Stone Walker lived was extremely interesting. There are a handful of women poets we run across commonly, but most of the poets I found were less well known. I had to search online and in specialized anthologies and obscure volumes not available at the library, writing down verses that seemed like they might provide an interesting complementary “note” for a theme or scene in my novel, and I collected many more than I used. I discovered poets and volumes of poetry I had never heard of, including one exquisite poem I used a few lines from but for which I could never track down information about the author (“Not Again,” by Mildred Amelia Barker). Partnering poetry with my chapters based on intuitive connections was an aesthetic and emotional puzzle.

KJ: Who is a poet that has inspired you most?

JV: The Russian poet, Anna Akhmatova, of whom it has been said that she has captured in her poetry the very land and soul of her country, and that feels true to me when I read her work. She paid a high price (she was a poet during the Bolshevik Revolution and beyond) and is inspiring as a strong woman as well as a poet. She was amazing, and I believe that all the Akhmatova poetry you might ever read had to be memorized by her because she had to destroy the evidence of her honest subversion of oppression.

KJ: You previously worked as police beat reporter—how has that experience shaped your fiction?

JV: I jumped out of college and into my Louisiana reporting job from a highly sheltered life, and learned quickly that there are a lot more characters, alarming and fascinating stories and lifestyles in the world than I had any inkling of. I also had some up-close exposures to extreme corruption through that job, and again, I had no idea such things were real, as embarrassing as that is to admit. A thick blindfold was torn away—I saw stories everywhere in the structure of life after that.

KJ: What’s next for you?

JV: Thank you for asking. In fact, thank you for asking all of these questions—they are extremely intelligent and interesting.

I am currently working on another novel, and this one also happens to include the presence of Lake Michigan, troublesome secrets, and a few characters wrestling with loss and love. Events from the past have a role in this narrative as they do in The Lake and the Lost Girl, and so far I am hypnotized by the whole process of listening to this tale ascend from nothingness onto my page.

**

Jacquelyn Vincenta began her writing career as a police beat reporter for a daily Louisiana newspaper. She established and acted for many years as managing editor for a publishing company specializing in international trade issues. She lives in Kalamazoo, Michigan, where she focuses on writing, environmental projects, family, friends, and nature.

October 12th, 2017 |

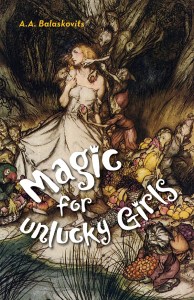

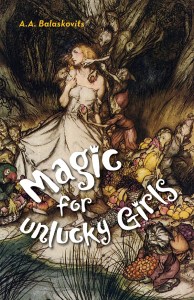

Midwestern Gothic staffer Kristina Perkins talked with author A. A. Balaskovits about her book Magic for Unlucky Girls, why fairy tales are the most dangerous stories, female monsters, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Kristina Perkins talked with author A. A. Balaskovits about her book Magic for Unlucky Girls, why fairy tales are the most dangerous stories, female monsters, and more.

**

Kristina Perkins: What is your connection to the Midwest?

A. A. Balaskovits: I was born and raised in the Chicagoland area (often, I say Chicago, but people from the actual city are quick to correct me). From there, I went to undergrad in Iowa, did my master’s in Ohio and my Ph.D. in Missouri. I live in the South now, but I miss the Midwest dearly. People are very enthusiastically polite in grocery stores down here. I miss shopping without expressing how my day is going every aisle.

KP: How does your relationship to the Midwest impact your writing?

AAB: I’ve come to understand more about the Midwest having lived outside of it. Down here in the South, everyone is polite, everyone waves at everyone else, and small talk is an art form. There’s a bit of that in the Midwest as well, in certain parts, but the Midwest is, to me, a land of people whose lives are defined by their work. They toil and, historically, have had jobs that saw down your bones through continuous and difficult labor. We’re polite, but we’re a realistic folk, and there’s a dark humor—a gallows humor perhaps—that is as unpredictable as the weather. I think that sensibility has been a major impact on my writing. A lot of my work is pretty dark, but it’s tongue-in-cheek as well.

KP: In your recent debut collection, Magic for Unlucky Girls, your stories span time and space, jumping from modern suburbias to ancient castles to American farmlands. How does your understanding of place—and, with it, your senses of belonging, familiarity, and adventure—influence these settings?

AAB: I have a very at-odds take with setting. A lot of other writers I admire use it to a great and often astonishing degree, but I tend to use it as “this is right for this story.” For the stories that do take place in a fairy tale world, that ever-so-wonderful once-upon-an-unspecified-time (but it’s totally in the past) I wanted to specifically comment on that genre, that kind of story. For the ones that take place in our farmlands or in suburbia, those stories comment on how the stories from our past still resonate within our communities today. We’ve never really escaped from them. If we think about fairy tales, they were told orally at first, written down, and then constantly rewritten to fit the expectations and mores of the time and place they were being retold. So, on one hand, I’m nodding to the past and its influence on me, but I’m also centering these stories in our world today because they reach out from the past and hold tight to our necks.

KP: Magic for Unlucky Girls plays beyond the limits of fairy tale, twisting, distorting, and breathing fresh air into the genre. What draws you to fairy tale, as a genre? What do you see as the purpose of the genre? How does your work contribute to, complicate, or alter this purpose?

AAB: The purpose of fairy tales is two-fold: They’re entertainment, but like all forms of entertainment, they teach a lesson. There is a heavy moralistic imperative to them. Unlike other stories, fairy tales are very decisive: Things are good or they are evil, and complexity is often hard to come by. They create a very one-dimensional world, and considering what an incredible influence they have held onto our cultural mindset, and continue to have, I think they are the most dangerous stories ever told. For the most part, my work in this collection has been to expose how dangerous they are, as well as twist them so they have more—and perhaps this is a strange word for it—realistic consequences. The men aren’t always gallant heroes or evil incarnate, and women are not passive princesses or clever girls waiting to be rescued. We’re all somewhere in between, but once you add magic to it, all hell breaks loose.

KP: Breaking from the genre’s tradition of one-dimensional heroes and archetypal villains, the female characters in Magic for Unlucky Girls are remarkable in their complexity: They are equal parts strong and malicious, independent and violent. In a previous interview, you note that this collection was driven, in part, by a desire to “explore women as monsters.” What inspired this desire? What do you seek to accomplish by embracing this side—the monstrous, the vindictive, the viscous—of your female characters?

AAB: We don’t really get to be monstrous, not really, in our daily lives. It’s unforgivable, for a woman, to break from archetypal roles, be it mother, daughter, lover, wife, etc. Go to any comment section of an article about a woman who broke the social bonds of their role and you’ll see how understanding we are about it. There is a precedent, of course, for the woman monster: Baba Yaga, Charybdis, Medusa, Lilith, the rusalki, mermaids, the Harionago, the stepmother. They’re often one-note and, a lot of times, are there to be defeated in a man’s more interesting and complex adventure. So I wanted to explore what it would be like to dive into the mindset of a female monster. That kind of monster is, certainly, a woman who simply does not act in their established role, or who is honest and reactive to their emotions, or who desires something they cannot have but tries anyway, or is furious with an injustice done to them or their loved ones. So an unrestrained human being. When I was growing up, I really longed for that kind of woman-protagonist. Someone who fucked up, was hurtful to others even if they did not mean to be, or in some ways exposed, through their own story, how messed up the world is. Monsters, in fiction, are reflections of our anxieties, and Magic for Unlucky Girls is a pretty anxious collection.

KP: As an editor for Cartridge Lit, you publish fiction, poetry, and nonfiction inspired by video games. How would you describe the relationship between writing and gaming? How has this position changed how you read and write—if at all?

AAB: It has! I play a lot of video games and love the medium. There’s a lot going on in games: One, you’re roleplaying, even if it’s not a traditional roleplaying game. Even if you’re stuck in the body of a squat, jumpy plumber, you do still grow to care about what happens to him and feel genuine frustration when he falls down yet another pit. Have you ever seen those animations of Sonic drowning in the water levels? Heartbreaking. So on one level, you’re connecting with the character, the actions you perform on the controller dictate their actions (and the thrust of the story) and, whether you play the game to the end or not changes how everything resolves. It’s made me think about the way that stories can be crafted. With a story or a novel, the author has complete control over what happens, but in a game, a lot of what happens will change depending on who is playing, their choices and their skill. Playing games has certainly made me consider the audience with a much more open mind: There’s what I want, but I have to write with a the reader in mind, and their imaginations could—and should—go anywhere.

KP: Who do you write for?

AAB: That’s a really interesting question. I think, honestly, that I am writing for a younger version of myself. I’m writing stories I would have liked to have read as a child. I did read a lot of dark, violent work—what we all consider Classic Western Lit—but I always felt the women in those stories were often relegated to side roles, prizes to be won by the male protagonist, or did not have a very vibrant inner life, and they certainly were rarely the types to have grand, epic adventures (though I did eventually come across those novels—they just weren’t in the Norton anthologies).

KP: What is the best piece of writing-related advice you’ve ever received?

AAB: To be okay with getting rejected and to always expect it. And, ninety percent of the time, that’s been accurate for me. So my expectations are pretty damn low, so it’s always a thrill when something works out. That, and, while I don’t think it’s ever been voiced but mostly been implied—get involved in a community, whether it’s writers or whoever they are for you. You’re going to need the support.

KP: What’s next for you?

AAB: I just finished a chapbook of short fairy tales—all under (or close to) 1,000 words—that essentially didn’t make it into Magic For Unlucky Girls. I’m trying to make that as perfect as possible, because I think these kind of stories still need rewriting. Additionally, I’m currently writing a novel that seems to get worked on in a great rush and then ignored for weeks at a time. The novel is going to be one of those grand, magical adventures that I would have liked to have gone on when I was a little girl, but with the sensibilities I have as an adult. So, you know, kind of dark, very violent, lots of fun.

**

A.A. Balaskovits is the author of Magic for Unlucky Girls (Santa Fe Writers Project 2017). Her fiction and essays appear or will appear in Indiana Review, The Madison Review, The Southeast Review, Gargoyle, Apex Magazine, Shimmer and numerous other magazines and anthologies. Her short fiction was named one of Wigleaf’s top 50 fictions in 2017. She was awarded the New Writers Award from Sequestrum in 2015 and won the grand prize for the 2015 Santa Fe Writers Project Literary Awards series.

October 5th, 2017 |

Midwestern Gothic staffer Meghan Chou talked with author Sharon Solwitz about her book Once, In Lourdes, the process of growing up, influential coming-of-age stories, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Meghan Chou talked with author Sharon Solwitz about her book Once, In Lourdes, the process of growing up, influential coming-of-age stories, and more.

**

Meghan Chou: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Sharon Solwitz: I was born in Pittsburgh, grew up in Beachwood, a suburb of Cleveland, married and divorced a man from Chicago, remarried a man from Minneapolis. We raised our children in Chicago and still reside there, four doors north of Cubs Park. I seem to be Midwestern through and through.

MC: In Once, In Lourdes, four teenage friends—Kay, Vera, C.J., and Saint—make a pact to sacrifice their lives by jumping off a lake cliff, called the Haight, after they live the next two weeks to the fullest. What does their pact show about teenage friendships and stepping into adulthood?

SS: In adolescence, friendship supplants the interest in and reliance on adults. Your friends are your universe, and their opinions and tastes and love or lack thereof become the touchstone of yourself. I see adolescent friendships as an essential step on the road to adulthood. Teenagers have to relinquish their dependence on their parents in order to understand themselves. For some years they replace dependence and love for their parents with dependence and love for their circle of friends. There’s nothing wrong with dependence; we’re social beings and need one another. But to become an adult, you have to enlarge and vary your group, the wider the better. I see growing up in Jungian terms as a process of individuation, of gaining access to more and more distant or recalcitrant parts of yourself—which enables you to form wider connections with other people. There may be other paths for the human heart and soul, but I haven’t figured them out yet.

MC: How does the suicide pact change the way Kay, Vera, C.J., and Saint approach the supposed last two weeks of their lives?

SS: Good question. Really, the central question. It makes them daring—dangerously candid, self-revealing. If you only have two weeks to live, you are less afraid of telling the truth to your friends, enemies, loved ones. The only one who doesn’t tell the truth is Vera, with disastrous consequences. She was the one who started the process, who challenged them, but she never told the whole truth.

MC: While the four friends try to cement their friendship forever, America fights in the Vietnam War across the world. How do the events of the ’60s influence the tone of Once, In Lourdes, specifically on topics of violence?

SS: At first all the evils of the Sixties, the social injustice, assassinations, the pointless, devastating war, are background to the world these kids live in. Lourdes is a resort town, fairly wealthy, and even the least privileged of the four friends is safe from most forms of want and physical danger. Current events form a kind of bass line against the four-part upper register of the characters’ thoughts and actions. Although they occasionally refer to current events, they remain largely subconscious, rising only at the end to the level of actuality.

MC: Since Once, In Lourdes follows teenagers in the summer before their senior year of high school, one could categorize the book as a coming-of-age story. How do you feel Once, In Lourdes fits in with and differs from other coming-of-age books?

SS: Whoa! Beeg question. Coming of age requires an encounter with oneself and others. Books that accomplish this? Catcher in the Rye, Little Women, “The Bear” (from Faulkner’s Go Down, Moses.) All of these books place their protagonists in a situation where they have to come to terms with death. Holden Caulfield is sharp, humorous, suicidal and hates most of the world, at the end arriving at a kind of marginal acceptance. The sisters, distinct personalities, are obliged to face the death of one of their band while the Civil War rages on. Young Ike is made to witness not just the death of the seemingly all-powerful bear, but of the wilderness and the antebellum Southern life that the book depicts. In a way, all of these are my influences—Alcott’s four loving and questing sisters, Salinger’s alienated school boy. But Faulkner is my touchstone. I want to write something as monumental as Go Down, Moses.

MC: On sensitive subjects, such as suicide, how do you as a writer tread the line between honoring and exploiting the topic for storytelling?

SS: Frankly, I don’t think about exploiting, don’t try to avoid it or stay on the other side of it. My goal is simply to write the truth of my characters as honestly and fully and deeply as I can. So there is no question of exploiting the topic, no glamorizing, or making suicide seem like something other than a tragic mistake. The result of a confluence of mistakes.

MC: Once, In Lourdes takes place in Lourdes, Michigan, in the summer of 1968. Why did you feel the Midwest, particularly Michigan, was the most fitting setting for this story about friendship?

SS: In my central image for Once, in Lourdes, the four characters align on a bluff, holding hands, about to jump to their deaths. I once drove along the Michigan coast in search of a house I never found, and I came across a house with a peach tree in front. The backyard was high above Lake Michigan and at the same time eroding, grass that was once part of the lawn growing down the nearly perpendicular slope. It was uncanny.

MC: What sort of research did you perform to accurately portray this time period?

SS: Ha! Most of it came from memory. I was at Woodstock too. I lived on a commune and rode a horse through Afghanistan. Honest to God. As for research, I did some Googling, for Allen Ginsburg’s “America,” and for other famous figures in the battle of Chicago. Most of it got absorbed by the imaginary, though.

MC: What’s next for you?

SS: I’m looking for a publisher for Abra Cadabra, a novel in stories about a family in which a child gets cancer. I’m in the middle of work on Boy in Exile, which took me to Israel, where I may need to go again. In that book, 20-year-old Jacob goes to Israel and disappears, and his schoolteacher mom (whose husband has just left her), goes in search of him.

**

Sharon Solwitz’s novel Once in Lourdes just came out from Random House (Spiegel & Grau). She has also published a novel Bloody Mary and a collection of stories Blood and Milk, the latter of which was a finalist for the National Jewish Book Award. Awards for her individual stories, appearing in such magazines as TriQuarterly, Mademoiselle, and Ploughshares, include the Pushcart Prize, the Katherine Anne Porter Prize, and the Nelson Algren Prize. Her stories and essays can be found in numerous anthologies and creative writing textbooks, and in Best American Short Stories 2012 and 2016. She teaches fiction writing at Purdue University and lives in Chicago with her husband, the poet Barry Silesky.

September 28th, 2017 |

Midwestern Gothic staffer Audrey Meyers talked with author John Smolens about his novel Wolf’s Mouth, writing from the point of view of the outsider, connecting imagination with research, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Audrey Meyers talked with author John Smolens about his novel Wolf’s Mouth, writing from the point of view of the outsider, connecting imagination with research, and more.

**

Audrey Meyers: What’s your connection to the Midwest? How has living in Michigan impacted your writing?

John Smolens: My Russian and Irish ancestors came to the United States under dire circumstances; I’m the product of that great American immigration story, and fortunate to have lived in various parts of the country, never having to move because of my religion (as in the case of my Jewish grandfather’s family) or my farm was seized by the British army (as in the case of my Irish grandmother’s family). Where you come from is important; where you go is, too. I was born in New York, raised in Greater Boston, and at the age of 32 attended the Writers’ Workshop at the University of Iowa. In 1985 I began teaching at Michigan State University, and have lived in Michigan ever since. So I’ve now spent more than half of my life in the Midwest.

AM: What is interesting about the Upper Peninsula and how do you capture this in your writing?

JS: Everything. I’m not sure I do capture the U.P. in my writing. Certainly not all of it. I don’t know that anyone can. It’s not just that it’s “big” in the geographical sense; conceptually, it’s too mercurial to grasp. Sometimes a book can offer glimpses of this place, and I hope mine does for some people.

AM: Since Wolf’s Mouth takes place in the mid-20th century, how do you make historical accounts relevant to the modern reader?

JS: It depends on the reader, really. The novel spans nearly a half century, beginning in 1944 and ending in 1991. While writing the book I didn’t think that I was consciously trying to make it “relevant”; but I hoped it would be a fairly accurate portrait of the second half of the 20th century. The narrator, Francesco Giuseppe Verdi (who later in the story changes his name to Frank Green) is born in 1919, which is the year my father was born. I did this so that as Francesco’s story unfolds, his age in a given year is the same as my father’s. It made it easier for me to imagine Francesco, say, as a man in his mid-thirties in 1956.

AM: What inspired you to write Wolf’s Mouth from the perspective of a foreigner in Michigan during WWII?

JS: A lot of stories and novels are told from the point of view of the outsider, as well as the doppelgänger. Francesco/Frank is, to a degree, both. Working through a perspective of unfamiliarity seemed essential to this novel. When I began reading about the POW camps that were here in the Upper Peninsula, the initial news stories said that the majority of the imprisoned soldiers were German. I’ve never been to Germany, but I have taught in Italy, and have visited the country seven or eight times since spending a half year there in 2003. I don’t know that I could have written the book from the perspective of a German soldier. But Italian, it was worth trying. Furthermore, the tensions that arise in the POW camp at Au Train (which is about 30 miles from Marquette, where I live) aren’t really between the prisoners and their American guards, but between the prisoners themselves.

It was interesting that the Nazis, whom their American guards often called “true believers,” took control of the camps. They were in the minority; many German soldiers, and certainly the men from other countries, were not ardent followers of Hitler. But the “true believers” were adamant, and they utilized threats and intimidation. There were instances where prisoners were injured and in some cases killed. In one camp, a soldier who had developed an appreciation for American jazz was ordered to stop listening to jazz recordings; when he refused, his ears were cut off. For the most part, the American guards allowed the prisoners to run the daily operation of the camps, provided that they performed the work that was expected of them. In the U.P. camps, this meant cutting wood for pulp production. Wolf’s Mouth is told from the point of view of an Italian officer, who is both an outsider in America, and also in the eyes of the ranking German officer in the camp, who is adamant that all the prisoners adhere to Nazi principles.

AM: Through this unique point of view, did Michigan as a whole change for you? In other words, what did you notice or see differently about the Midwest while describing it in Wolf’s Mouth? Further, how are the themes of nature and regionality utilized in your novel?

JS: The first portion of the novel, Francesco is in the camp at Au Train, but after he escapes he remains in Michigan after the war. A small percentage of POWs did this; out of about 425,000 men who were brought to the camps in America (there were at least 170 camps throughout the country), approximately 2,200 men were somehow unaccounted for at the end of the war. Some fell through the bureaucratic cracks, I suppose, but a good number of them managed to remain in the United States; they changed their identities, and many lived for years here.

Francesco/Frank is a chameleon, and an astute observer. In order to survive in America, he learns to speak and look and behave like an American. By Part Three of the novel, he’s living in Detroit in the mid-fifties; he’s married, has a small business, and he’s a guy who after work sits at a bar, drinking Stroh’s, listening to the Tigers game on the radio. While writing this portion of the novel, along with reading news accounts, I gathered images from the period. Who called the Tigers games on the radio broadcasts in ’56? Who was in their bullpen? What were the popular songs that year? One of the hits in ’56 was “Que Serà Serà,” sung by Doris Day in Alfred Hitchcock’s movie The Man Who Knew Too Much. (Though the phrase is supposed to be Italian, meaning “Whatever will be will be,” the first word Che was changed to Que, because someone in Hollywood felt that an American audience was more familiar with Spanish.) I studied clothing, shoes, and cars. Because Frank has a small shop that sells lampshades (both retail and wholesale), I researched lamp shades. The name of his shop is Made in the Shade.

AM: What did you learn about yourself as a writer when creating a Wolf’s Mouth?

JS: I’m not sure how to answer that. It suggests that I take some kind of personal lesson or insight from my own books. Oddly (perhaps), while writing this book (and others) I’m of two minds (at least two, actually): I’m thoroughly steeped in the characters, to the point that they and the world they inhabit seem utterly real to me; and at the same time I feel quite distant from the whole enterprise. I don’t know if this is a matter of my own survival, or what. I do know I’ve read other novelist say how once they’ve finished a novel it’s like it’s not even theirs. I know what they mean.

AM: What genre do you think Wolf’s Mouth falls under? Why?

JS: I’m not fond of the notion that novels have to fit in a particular genre. Perhaps it’s easier to market them, but most novels contain elements we associate with several categories. Some—not all—of my books I suppose are considered “historical fiction,” simply because they are set in the past: the first months of the American Revolutions in 1775; an epidemic of a deadly fever in 1793; anarchism and political assassination in 1901; JFK’s assassination (1963) and the Salem witch trials (1692). Wolf’s Mouth is narrated by a man who is born in 1919, and it concludes when he’s an elderly man in 1991. Where does history give way to contemporary? For me, the fifties are contemporary; for a younger reader, the fifties is ancient history. I subscribe to the notion that the past and present are ineluctably linked.

AM: What research or references did you depend on for this book? How did implementing historical facts affect your writing, and were there any obstacles? How did you overcome them?

JS: I couldn’t write a book like Wolf’s Mouth without reading history, incorporating elements that I found in newspaper articles, interviews, books, etc. Some years ago, there was a novel (the name of which I forget) that won the Pulitzer Prize; it was set in a South American country (which one, I also forget), and when the author said in an interview that she had never visited that country there followed considerable criticism. Though I understand why there was such an outcry, the fact is she has the right to write about a place she’s never visited. A novel is, after all, considered a work of the imagination (“imaginative writing” is sometimes treated as an oxymoron, particularly by people with PhDs in literature). When I wrote about the American Revolution in The Schoolmaster’s Daughter, which was based on real events and, in some cases, people who lived in Boston in 1775, it was an exercise in the imaginary, regardless of how much research I did (and it was considerable). We can’t go back and visit the Battle of Bunker Hill. However, for me, attempting to find out what people were like during a given historical period is essential to writing a novel about that period. Diaries, letters, histories, articles, maps (I love maps)—I want to absorb as much as I can before I begin a book, and the search for material continues while I’m writing.

AM: What themes of Wolf’s Mouth resonated with you the most and why?

JS: One theme, really: survival. Jim Harrison thought all novels are about love, death. And perhaps food. I think some, including Wolf’s Mouth, are about survival.

AM: How do you make a tale an “American tale?”

JS: That’s an intriguing question. It’s not as easy as simply setting a novel in America. Some works of fiction have been set in other parts of the world and yet are truly American—which could also be said for British novels, maybe because England was an empire for generations. Think of E. M. Forester’s A Passage to India. As much as I love America, I don’t believe I’ll ever reach a point where I can say I know America. Perhaps that’s why I (and others) write about it? Actually, the older I get, the less I feel I know or understand who and what Americans are, and to pursue that line of thinking one would have to enter into an extended discussion of our current political and culture climate, and at the moment, as we are wont to say, I’m not going there.

Over the years, I read so many works of fiction with my students. William Carlos Williams’s short story “The Use of Force” and Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery” are truly American stories. However, The Handmaid’s Tale, which is set in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and written by Margaret Atwood, who happens to be Canadian, also seems very much an American tale (though not exclusively so). E. L. Doctorow’s Ragtime was on my syllabus several times. One might say that it’s an American novel, yet there is a palpable “foreignness” about it. So there is no easy answer here, and justly so. If we can clearly define America, and the American tale, we might not bother to write novels about America. That would be an American tragedy, so to speak.

AM: What’s next for you?

JS: This spring three of my earlier novels have been reissued in paperback and as e-books by Michigan State University Press: Cold, Fire Point, and The Invisible World. Later this year, another of my earlier novels, The Anarchist, will also be reissued. Having these books reissued is truly gratifying. My next new novel will be published (also by Michigan State University Press) in 2018; it’s what I consider a “sort of sequel” to Cold. It’s set in the U.P. and it’s called Out.

And beyond that, who knows? I tend to binge read—just find what I can about a subject and go at it. For a good while I’ve been reading about 1927. An amazing year. I suspect there’s a story there.

**

John Smolens has published ten works of fiction, most recently Wolf’s Mouth, which has been selected as a Library of Michigan Notable Book for 2017. Four of his earlier novels, Cold, Fire Point, The Invisible World, and The Anarchist, will be reissued in paperback by Michigan State University Press in 2017. His new novel, Out, which is a sequel to Cold, will be published in 2018 by MSU Press. His work has appeared in publications such as The North American Review, The Southern Review, The Massachusetts Review, The Virginia Quarterly Review, Columbia Journal of Literature and Art, The Boston Globe, The Los Angeles Times and The Washington Post. He was educated at Boston College, the University of New Hampshire, and the University of Iowa, and he has taught at Michigan State University, Western Michigan University, and is professor emeritus, Northern Michigan University. In 2010, he was the recipient of the Michigan Author of the Year Award from the Michigan Library Association.

September 21st, 2017 |

Midwestern Gothic staffer Audrey Meyers talked with author Christian Winn about his short story “What’s Wrong With You is What’s Wrong With Me,” following his own advice, the right time to write a story, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Audrey Meyers talked with author Christian Winn about his short story “What’s Wrong With You is What’s Wrong With Me,” following his own advice, the right time to write a story, and more.

You can read his short story here.

**

Audrey Meyers: What’s your connection to the midwest?

Christian Winn: I am really a westerner, having grown up Eugene, Palo Alto, and Seattle, and then moving to Boise nearly twenty years ago. Boise is the furthest east that I have ever lived. Most of my fiction is set in the west – Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Nevada, California – where I feel most comfortable telling the stories right. Boise and Idaho overall are generally considered in the Intermountain West, but I think you can look at Idaho as perhaps the far west of the midwest. I have road tripped through the heart of the midwest a handful of times, can’t claim to know it intimately, but love the vast openness of it all.

AM: How has being a professor at Boise State University impacted your writing? What have you learned from your students?

CW: I really am always inspired by, and learning from, my creative writing students. Teaching fiction writing workshops, I feel, continually helps me evolve as a writer. Introducing contemporary short stories and modern classics to both young and experienced writers, I am constantly learning how to look at the fundamentals of storytelling in new ways because of the fresh takes my students offer to the workshop. As well, I am constantly having to ask myself if I am actually practicing what I preach as a writer. I suppose I can sound like I know what I’m doing most of the time, but I always try and ask myself if I am following my own advice, and the advice of the great writers that we read. Keeps me on my toes.

AM: What are the challenges and the benefits when writing short stories? How does this compare to writing longer forms of fiction?

CW: I love the short story form, in all its many forms. Short stories, I feel, are kind of the underdog of the literary fiction world, and often I equate writing and reading short stories and collections to listening to a slightly underground indie album, that band that not too many have heard of and I feel special to know. Both in writing and reading short stories I often feel like the insider, exposed and enlightened by shorter narratives that, when done well, are as impactful and memorable as any novel. I do love so many novels, and have now written a couple that are hopefully finding a good home soon. But, I have gravitated more to the short story in a manner beyond the novel thus far in my life as a writer, teacher, and reader.

AM: What are your techniques for conveying information to your readers in an efficient but clever way? And how did you utilize these techniques in your short story “What’s Wrong With You is What’s Wrong With Me?”

CW: In “What’s Wrong With You is What’s Wrong With Me” a number of my baseline tenets and techniques as a writer came into play – thorough characterization, sharp and unique voice, vivid setting, true conflict rising into crisis then resolution. In creating the protagonist, Samantha, as a snappy and slightly snarky woman in her early twenties, I was working to deliver a character who was putting up a kind of front in the face of a lingering and very-present tragedy – the loss of her older sister, Mary. I wanted to create an interesting and complex secondary character in her brother, Johnny, who was Mary’s twin and closest friend. As well, I worked to send them on a spontaneous quest – a road trip to their childhood home in Boise in a “kind of” stolen BMW that belongs to Johnny’s wealthy, older boyfriend. Then to ratchet up the tension, I introduced the heightened drama of their old house having been demolished to make way for the building of an apartment complex.

AM: When you get an idea for a story, how do you decide if it is the right time to write it?

CW: I’d say that this is really difficult question to answer for me as a writer because the process of story selection – when to write what – is so often shifting, morphing, evolving. Certain stories at certain times, they ask to be written, they need to be, and I do my best to get them written. But, there is definitely deeply rooted discipline in writing a story that tells you it’s the “right time” to write me. Sticking with those stories is not always easy because you don’t want to let them down, or tell them wrong.

AM: Why was it the right time to write “What’s Wrong With You is What’s Wrong With Me?”

CW: Well, it was a piece that I had begun writing, or at least had the initial idea for, a few years ago when a local church actually did buy a big piece of property and begin either moving, or demolishing these great 100-year-old houses in order to build an apartment complex. It made me think, what if one of those was the house you grew up in, and you returned to try and reconnect with your past only to find that this huge piece of your physical past had gone missing? I wasn’t sure what to do with the story from there until the voice of Samantha started talking to me one day, and the rest came piece by piece, scene by scene.

AM: As a writer, what is it like to see a familiar place through your character’s eyes? Did your perspective on Idaho change when writing “What’s Wrong With You is What’s Wrong With Me?”

CW: Seeing Idaho, and Boise in particular, through Samantha’s eyes allowed me to think about the state and city where I live from the point of view of a person who grew up here (as I did not), but also who has not returned to it for many years. The experience allowed me to take a fresh look at the neighborhood and city I walk, bike, and drive through just about every day of my life these last years. I wouldn’t say this experience opened up a fully “changed” perspective of Idaho, but it offered a few cool new angles.

AM: What did you learn about yourself when developing these characters?

CW: This is another tough question to answer without sounding too corny. But I feel I learned a further sense of empathy and understanding for siblings who have lost one of their own at a young age, another thing that fortunately I have not experienced. I certainly learned how Samantha and Johnny feel about the loss of Mary, and through that I hope that I was able to further understand how we work as humans at a baseline level.

AM: What genre or style of fiction would you label “What’s Wrong With You is What’s Wrong With Me?” Why?

CW: I would consider this story literary fiction, meaning that the characters – their conflicts, their voices, their takes on the world – are what drive the narrative, not simply the plot points, the setting, or the quest.

AM: How do you know when a story is finished?

CW: This definitely varies with every story I’ve ever written, but I’ll just speak to the ending of “What’s Wrong With You is What’s Wrong With Me” here. With this story, which pretty much operates within straight-up realism most of the way through, it wasn’t until I came across a writing moment that shifted wonderfully toward the dreamlike, the surreal, that I knew (or at least thought I knew) that I had my ending. I won’t divulge the specifics of the longer last paragraph that gets a little strange and hopefully poetic, (no spoilers!) but I will just say that Samantha is able to reach a kind of resolution and relative peace in a dream-layered story she will tell herself forevermore about her dead sister, Mary.

AM: What’s next for you?

CW: Well, this September a new collection of four longer stories, with the title story being “What’s Wrong With You is What’s Wrong With Me” will be released from Dock Street Press. As well, I have those two “incubating” novels, and a new collection of short stories I am shopping around. I’ve been writing a lot of poetry as well, and hope to get the poetry collections titled Stories About Girls, By Boys, and Every Day, A Gun out into the world soon. As well, I have the exciting privilege of being the 2016-2019 Idaho Writer in Residence and get to travel around the state giving readings, putting on workshops, and providing literary outreach to under-served communities.

**

Christian Winn is a writer of fiction, poetry, and creative nonfiction living in Boise, Idaho. His work has appeared in McSweeney’s, Ploughshares, The Chicago Tribune’s Printers Row Journal, TriQuarterly, Gulf Coast, and elsewhere. His debut collection, Naked Me, is recently out from Dock Street Press who will be publishing his second collection, What’s Wrong With You is What’s Wrong With Me in September 2017. He is 2016-2019 Idaho Writer in Residence.

September 14th, 2017 |

Photo credit: Thaiphy Media

Midwestern Gothic staffer Kathleen Janeschek talked with poet Bao Phi about hatred from lack of understanding, approaching his work naturally, being a champion slam-poet, and more.

**

Kathleen Janeschek: What is your connection to the Midwest?

Bao Phi: Even though I was born in Vietnam, my family fled and came to the Phillips neighborhood of South Minneapolis when I was a baby. I’m pretty much a lifelong Minnesotan.

KJ: How does the varied geography of Minnesota inform your writing?

BP: When I was very young, I remember my family had a lot more connection with rural people in Minnesota. I think because we came from a country that was still very close to agriculture. We would go out to farms fairly often, and buy vegetables and meat directly from farmers. And farmer’s markets every weekend. But Phillips, where I was raised and where my parents still live, is very much the inner city – Minneapolis’s largest, poorest, and most racially diverse neighborhood. The Little Earth housing projects is two blocks from my parent’s house, and the Franklin Avenue Library, where I learned to love books, about six blocks away. My dad would often take me on fishing trips, sometimes by a mucky pond by the highway, sometimes renting a trailer at Mille Lacs. Not for sport, but for food. I got to know the city by skateboard in my junior high days, and as I got older, I go out to Greater Minnesota, sometimes for work, sometimes as a tourist. My father always tried to instill an appreciation for nature in me, and I am trying to pass that along to my daughter.

KJ: In which ways do the people of Minnesota contrast with the landscape of Minnesota?

BP: It’s funny, in the old days, I felt like the people we met in rural areas of Minnesota were more open to us. They approached us with curiosity and were very friendly, whereas people in the city seemed really racist and violent and intolerant. Families like mine were often blamed for the Vietnam War, even though my father fought on the same side as the Americans – people didn’t understand, and back in the old days it seemed like most of that hate was in the city. In terms of the people and contrast – that’s hard to say, honestly. I’ve lived here so long that I’ve gotten to meet all different types of Minnesotans, so I find it difficult to generalize. I would say the perception of Minnesotans by outsiders, however, is that we are unsophisticated, boring, minor. I don’t think that’s true, obviously.

KJ: Your poems often switch between conversational and formal language. Is this transition intentional or something that naturally occurs in your writing?

BP: It’s a combination of how I write and what happens during the editing and revision process. It’s also probably about who I am – I went through a creative writing program, but as a spoken word artist, back when the idea of a spoken word artist going through a creative writing program was somewhat rare. I also often think of something the great poet R. Zamora Linmark advised me: “don’t edit the duende out of your poetry.”

KJ: Likewise, many of your poems include words or phrases from Vietnamese. What do you hope to achieve from this medley of languages?

BP: It’s just a part of who I am. I try not to force it – I tend to use it as I would naturally use it in real life, especially with the newer work.

KJ: In American discourse, there is often a conflation between the black experience, urban experience, and poor experience. How do you seek to challenge these narratives in your writing?

BP: First of all I think it’s tremendously important to lift up and support Black, urban, poor voices and art. Simultaneously it is important for us to challenge the dominant racist archetype of the Asian as the successful, overachieving model minority that doesn’t struggle against racism in this country, or against empire and colonization. I think the key word there is simultaneously – because often, we in America get caught in binaries and competition. Asian American struggle is often obscured by the model minority myth, but I want to make it clear that this is not the fault of Black people and Black voices. Those of us on the margins – Black, Native, Asian American, Latinx, Arab, Middle Eastern, Queer, Women, and all intersections of those identities – often get boxed into one or two simplistic narratives. My hope is to challenge and explode those simplistic, un-nuanced narratives.

KJ: How do your Vietnamese and Asian identities influence your writing? Do you ever find these identities at odds with one another?

BP: Tricky. I think Viet Thanh Nguyen, author of The Sympathizer, said it best: many of the contemporary Asian American movements are rooted in the collision of third world alliance, Marxism, and socialism, but many Vietnamese in America are here due to conflict with the Communist Party of Vietnam, and so a lot of Asian American liberation rhetoric can be triggering for Vietnamese people, especially of a certain generation. It’s a challenge that should be familiar to all writers: how do you stay true to your ideals and beliefs while not alienating your community – and how do you do that artistically? It’s a constant struggle.

KJ: You’re also a slam poet–and a two-time Minnesota Grand Slam champion and a National Poetry Slam finalist–so what has slam poetry taught you about written poetry?

BP: Urgency, passion, overcoming your fear, communicating difficult ideas and stories to an audience. But honestly that’s where my interest in poetry was before I slammed. I was in Speech Team, Creative Expression, at South High school back in 1992 and 1993. We were one of the few inner city schools that competed in Speech back then. So usually I was competing against suburban white kids who wrote funny essays, and here I was, this intense, awkward, Vietnamese refugee from the hood with braces and bad acne doing angry poems about racism. Sometimes it went over surprisingly well, and sometimes, well, you can guess some of the comments I got from the white suburban judges. You know, racism doesn’t exist, anger isn’t the answer, etc. But all of that prepared me to create armor for myself.

KJ: Are there any notable differences in your creative process when working with slam poetry or written poetry?

BP: No. I write poetry, and then I figure out what’s the best way to perform that poetry in front of an audience. The reading/performance of poetry is, in itself, craft.

KJ: What are some of your greatest influences in media other than writing (eg: film, music, art, etc.)?

BP: Everything – movies, television, comic books, all types of books (moving for me always sucks because of my book collection), music, table top role playing games, video games.

KJ: What’s next for you?

BP: I’ve been pretty much writing a poem a day for the last two or three years, though sometimes I take a “vacation.” I’m kind of writing a fractured memoir in verse, kind of writing some poems about a Chinese delivery boy who opens a door to an alternate dimension. I’m a single co-parent, so i’m trying to raise a kid while working as Program Director at the Loft and continuing my artistic practice. I have my first children’s book, A Different Pond, illustrated by the great Thi Bui and published by Capstone, coming out this summer, and my daughter has requested my next children’s book be about her. I’m looking at two bedroom domiciles for me and my daughter on one person’s salary which puts me in competition with dual income households with no children in a cutthroat housing market, which means I picked a bad time to get off anti-depressants.

**

Bao Phi is a two-time Minnesota Grand Slam champion and a National Poetry Slam finalist whose poems and essays are widely published in numerous publications including Screaming Monkeys, Spoken Word Revolution Redux, and the 2006 Best American Poetry anthology. The spoken word series he created at the Loft Literary Center, Equilibrium, won the Minnesota Council of Nonprofits Anti-Racism Initiative Award. His second collection of poems, Thousand Star Hotel, was also published by Coffee House Press on July 5, 2017, and his first children’s book, A Different Pond, illustrated by Thi Bui, was published by Capstone Press in August of 2017.

September 7th, 2017 |

Photo credit: Aaron Mayes

Midwestern Gothic staffer Audrey Meyers talked with author Olivia Clare about her book Disasters in the First World, sentence-driven characters, feeling her way into an ending, and more.

**

Audrey Meyers: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Olivia Clare: I lived in Iowa for two years while I attended the Iowa Writers’ Workshop for poetry. I’d never lived in the Midwest before. I remember anticipating encounters with cornfields, definitely, and I also knew I’d be joining a wonderful literary community in Iowa City.

I saw snow for the first time in Iowa. When I saw an ice scraper in the trunk of a friend’s car, I had to ask them what it was. I remember friends freezing while they smoked cigarettes on my back porch.

I was also a bit of a hermit, and much of my time was spent reading and writing. On some weekends I’d venture out on long drives. There’s a vastness in Iowa that allowed thoughts to come to the surface that hadn’t before.

AM: You’ve lived all over America from Louisiana to California to Texas. How have your travels impacted your writing?

OC: I’ve been fortunate to travel a good deal, and those places stay with me in my writing. For example, in June 2010 I went to Iceland just after Eyjafjallajokull erupted. I stayed in Reykjavik and in a rural dale called Skorradalur. I was in Iceland for about 6 weeks. After that trip, I wrote “Petur,” a story about a mother and son in Iceland just after the eruption of Eyjafjallajokull.

At the same time, travel and uprooting yourself over and over can be hard on the writing life. It’s difficult to establish a routine. My notes get lost on napkins or tickets or receipts. Or I’ll just neglect to write things down. So much of my writing happens when I’m feeling settled at my desk.

For the last 15 years or so, I’ve lived in about 10 different places, hopping around for various reasons. I once prided myself on being able to fit all of my belongings in my car. I’m settled in Texas now (I’m a professor at Sam Houston State University), and I’m very happy to call Texas home. I plan on some travel this summer.

AM: What is a disaster to you? How is this reflected in your book Disasters in the First World?

OC: Don DeLillo says that “catastrophe is our bedtime story.”

My story collection is thinking through what constitutes a disaster. Acts of nature—volcano eruptions, meteorites, droughts. But also: domestic disasters, individual disasters, personal—infidelity, anxiety, loneliness, estrangement.

AM: Why did you decide to write thirteen stories within Disasters in the First World? How does each piece of this structure relate to overall theme of the book?

OC: I originally had 14 stories, but I wanted to cut one of the stories in the end, and my editor agreed. I’ll admit that at first I was a touch superstitious about that; the number 13 felt ominous to me. But then I had a different thought: “unlucky 13” could be thought of as a disastrous number. Thirteen is a great number for the book, I decided.

AM: How do your characters represent humanity?

OC: My characters are constantly struggling with intimacy and how to achieve it—intimacy in friendships, familial relationships, romantic relationships. They struggle with their sensitivity and what to do with it.

AM: What aspects of human nature do you focus on in Disasters in the First World?

OC: I write a good deal about longing and the uncertainty that comes with it. Wanting to believe in things that aren’t there. Wanting to speak to things that aren’t there…a certain kind of longing that reaches to and past other humans. Those are the aspects of human nature I’m most interested in for the book.

AM: What genre or style of fiction would you label Disasters in the First World? Why?

OC: I think of these stories as character-driven. But they’re sentence-driven, too. The characters will often tell me where the stories need to go, certainly. Sometimes the sentences tell me the story, too. If I’m struggling with plot, I keep trusting the sentences, one by one. They’ll lead the way.

AM: How do you know when a story is finished?

OC: My background in poetry helps me with this. I often approach the ending of a story the way I approach the ending of a poem. Sometimes the ending will come to me in the rhythm of a sentence. I know the rhythm that I want, and I have to put in the words. I put my ear to work quite a bit in my writing, and that’s especially true for the ending. Sometimes I’ll know the tone of the ending before I know what words go there.

I often feel my way into the ending, and that’s a particular feeling that poems—reading and writing poems—have taught me. I think of it this way: sticking the landing, but giving it a little lift, too.

AM: What’s next for you?

OC: I’m finishing a novel that takes place in southern Louisiana, just after Hurricane Katrina. After that, I have plans for a book of linked stories about three sisters. It’s possible that manuscript will become a novel; if it does, I’ll have a manuscript of short stories going at the same time. I’m too committed to the short story to abandon the form for too long. New poems are underway, too.

**

Olivia Clare is the author of a short story collection, Disasters in the First World, from Black Cat/Grove Atlantic. She is also the author of a book of poems, The 26-Hour Day (New Issues, 2015). Her fiction has appeared in Granta, n+1, Boston Review, Southern Review, and The O. Henry Prize Stories 2014, among other publications. Her poems have appeared in Poetry, Southern Review, London Magazine, FIELD, and elsewhere. She holds master’s degrees from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and the University of Southern California, as well as a PhD from the University of Nevada. She is an Assistant Professor in Creative Writing at Sam Houston State University.

August 31st, 2017 |

Photo credit: Willy Somma.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Kathleen Janeschek talked with author Catherine Lacey about her book The Answers, constructing the ideal relationship, marbles vs. dog shit, and more.

**

Kathleen Janeschek: What is your connection to the Midwest?

Catherine Lacey: A rather tenuous one. In the last couple years I’ve been traveling almost constantly, but I moved my home base to Chicago in 2016 because it’s where my partner, Jesse Ball, lives and teaches. However, I quickly whisked him off to Missoula, Montana where I was teaching for a semester. Now we’re back. So, the last year has been a rather midwestern one. We even drove through a blizzard.

KJ: Both of your novels have been set in New York City, but you live in Chicago. What inspires you to write about one city while living in another?

CL: Because book publishing takes so long, I actually wrote all of The Answers while I was living in New York, which was home for nine years. Half of the first one is set in New Zealand, which I wrote because I had been to New Zealand and wished I had never left.

KJ: Your latest novel, The Answers, centers on Mary, a woman who suffers from chronic pain. How did you approach the subject of chronic pain? What kind of research did you do?

CL: Having a body, as vulnerable as anyone’s, is enough research if you pay close enough attention. I’ve never been as ill as Mary is at the book’s opening, but I’ve had some frustrating health problems that gave me a window into what that would be like.

KJ: Another character of the novel is Kurt Sky who is attempting to create the perfect girlfriend by having a multitude of women each portray different aspects of a relationship. What inspired you to write about someone who viewed relationship in fragments?

CL: When I began writing the novel in 2013 the idea and impossibility of constructing some sort of ideal relationship was on my mind, so it came out in my work. It’s actually not clear to me whether Kurt thinks of all the women he’s hired as a “the perfect girlfriend.” He is, at least, hoping that the experiment will make discoveries that could make a “perfect” relationship possible.

KJ: Do you consider this portrayal a commentary on human connections in modern life?

CL: No.

KJ: Why did you choose to make the middle section of the novel – the part dominated by Kurt’s girlfriend experiment – third person, while keeping the opening and ending sections first person?

CL: I just had this sense that the perspective needed to shift in order for the scope of the book to function as it does now. I fumbled around with other ideas, but this is the one that took.

KJ: The Answers manages to be both an emotional narrative and a big ideas book. How do you balance plot and concepts in your writing?

CL: I honestly do not know. I’ve learned everything by accident. When I write I tend to feel like I am bushwhacking instead of following a path.

KJ: Though definitively literary fiction, The Answers has science fiction vibes. What are some of your science/speculative fiction influences?

CL: I can think of three books that influenced, directly and indirectly, this aspect of The Answers: Helen DeWitt’s Lightening Rods; Kobe Abe’s The Face of Another and Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We. My knowledge of real science fiction is pretty limited, though.

KJ: How has writing your second novel compared to the first? Do you think you’ve learned anything?

CL: Writing the first one sort of felt like I was wandering around blindfolded, wearing big mittens, trying to pick up marbles off the floor without slipping on them in the process. Writing the second novel…well, honestly it was pretty much the same thing except I realized halfway through it that a third of the marbles I’d picked up were actually little hardened pieces of dog shit and I had to throw them away and find more marbles. In the year and a half since I finished writing The Answers I have been working very differently, so maybe it took two novels to learn something? I don’t know if I can describe what is different now, but something is different and I’m happy about it. I’ll probably unlearn it and have to learn some other way to be.

KJ: What’s next for you?

CL: I’ll probably walk my dog and go to the bookstore. Later it will be time for dinner. The sun will go down, then come up. Then it will be time to sit and think for a while.

**

Catherine Lacey is the author of the The Answers and Nobody is Ever Missing. She was a 2016 Whiting Award winner, was a finalist for the NYPL’s Young Lions Fiction Award and has earned fellowships from the New York Foundation for the Arts, the Omi International Arts Center, the University of Montana. In 2017 she was named one of Granta’s Best Young American Novelists. Her work has been translated into German, Italian, Spanish, Dutch and French. Her first short story collection, Certain American States, will be published in 2018.

August 24th, 2017 |

Midwestern Gothic staffer Meghan Chou talked with author Sarah Manguso about her book 300 Arguments, indulging a writing habit, finishing pieces, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Meghan Chou talked with author Sarah Manguso about her book 300 Arguments, indulging a writing habit, finishing pieces, and more.

**

Meghan Chou: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Sarah Manguso: I went to the Iowa Writers’ Workshop in the nineties — my first westward traversal of the Mississippi!

MC: 300 Arguments reads like essays constructed in the form of poems with each line a parable, life lesson, or provoking thought. How did you develop this genre-blurring format?

SM: After working relatively fruitlessly on a different book, I found myself turning away from it in order to write very short pieces of prose — very short, but complete in themselves. They provided an antidote to the frustrating, enduring incompleteness of the other book, and they eventually became a different book.

MC: A review on NPR called 300 Arguments a “poem of quarrels,” where each line seems to fight the line before and after in an existential battle. What reaction did you hope to provoke in your readers? Did you want to start an internal “quarrel?”

SM: My definition of the word argument isn’t limited to quarrel but includes a more varied grab-bag drawn from the word’s archaic meanings: subject, theme, sign, mark, token, proof, hint, plot, declaration, evidence, burden, complaint, accusation, denouncement, betrayal. I wasn’t interested in either starting or avoiding an internal quarrel. I just wanted to finish something. Or 300 somethings.

MC: You once said to “think of [300 Arguments] as a short book composed entirely of what I hoped would be a long book’s quotable passages.” Why did you want to include only the most memorable lines?

SM: I didn’t start out wanting anything, really — I was just indulging a habit that eventually became a book. That argument you quote above was written relatively late in the project, after it was nearly done.

MC: Various authors have equated deleting lines and phrases to “kill[ing] your darlings.” For 300 Arguments, what was your editing process in order to build such a condensed book?

SM: I’ve seen this line attributed to various folks, but it’s Arthur Quiller-Couch: “If you here require a practical rule of me, I will present you with this: ‘Whenever you feel an impulse to perpetrate a piece of exceptionally fine writing, obey it—whole-heartedly—and delete it before sending your manuscript to press. Murder your darlings.”

AQC instructs us to strike out our prideful flourishes, the artifacts of self-love, the passages in which we’re listening to ourselves write—to leave room for the writing itself.

I don’t think 300 Arguments even has darlings, by that definition—the sections are too short. On the other hand, maybe the entire book is just one darling after another.

MC: Which aphorism argument in 300 Arguments is your favorite?

SM: Every time I’m obliged to read from it I find that my tastes have changed, but I’m usually partial to the shortest ones.

MC: 300 Arguments addresses a wide range of key questions of the human condition from love to death and beyond. Is there a central message or evolution of ideas you want to convey?

SM: No, there is no single, central argument.

MC: What’s next for you?

SM: It’s back to work on the other book — for now, at least.

**

Sarah Manguso is the author of seven books including Ongoingness, The Guardians, and The Two Kinds of Decay. She lives in California.

August 17th, 2017 |

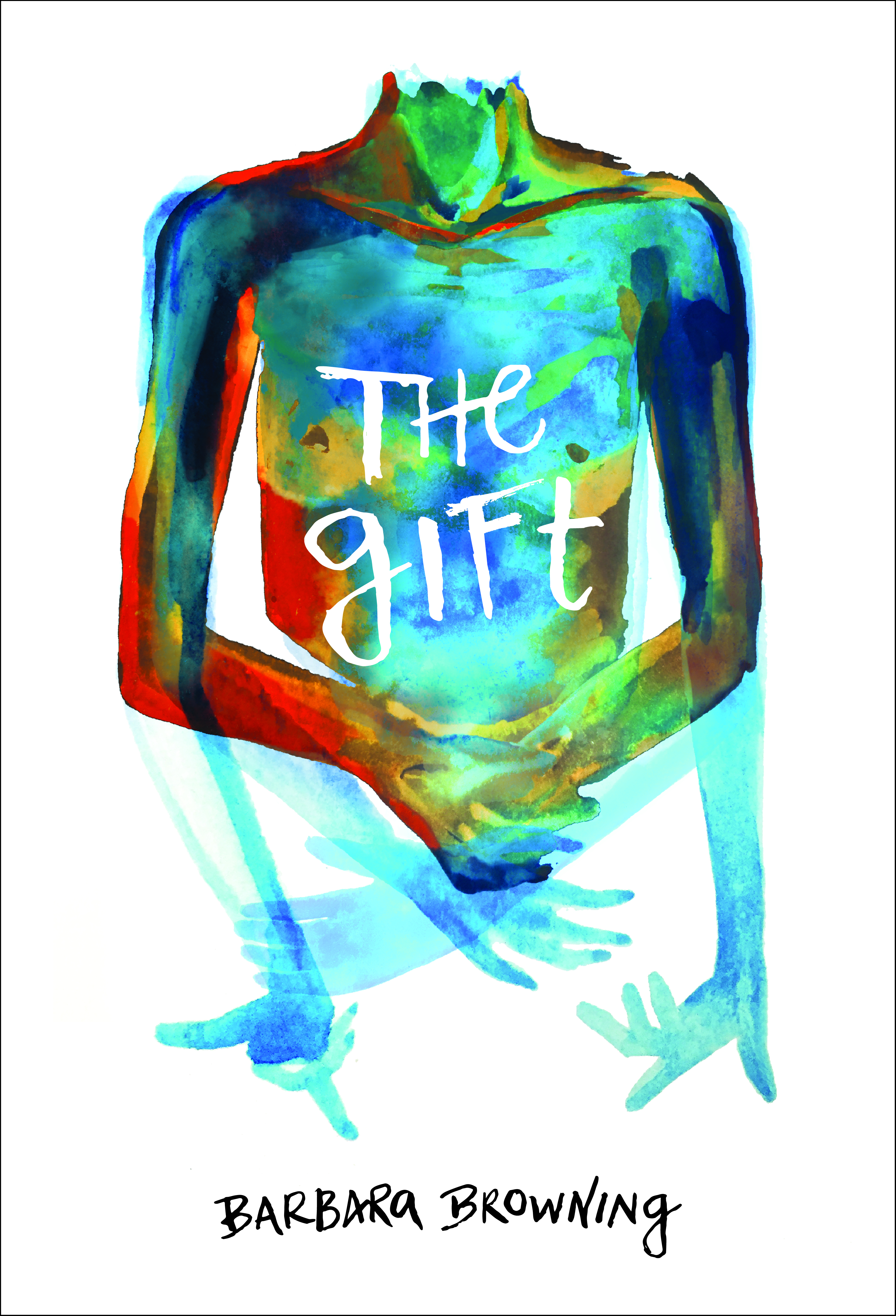

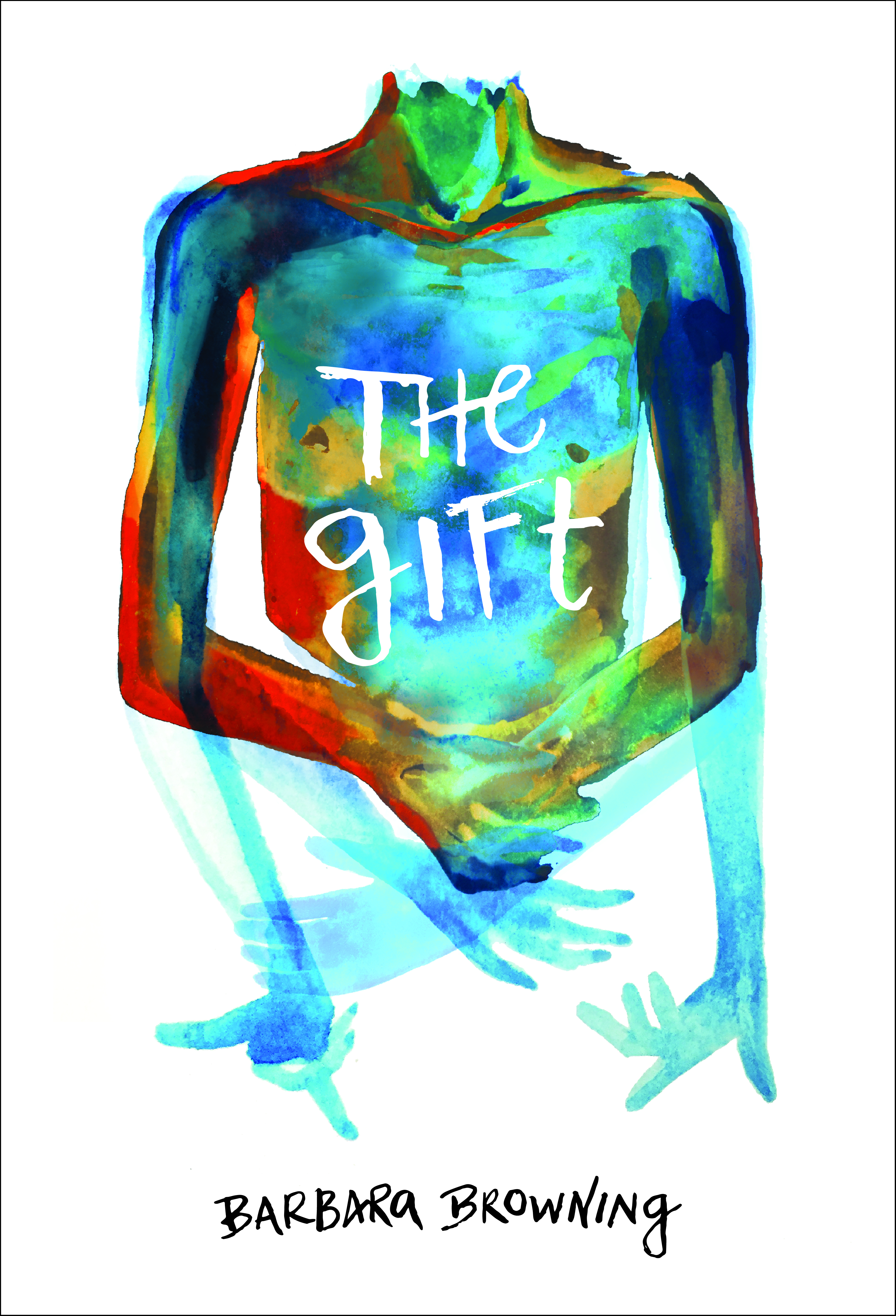

Midwestern Gothic staffer Audrey Meyers talked with author Barbara Browning about her book The Gift, virtual intimacy, collaboration, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Audrey Meyers talked with author Barbara Browning about her book The Gift, virtual intimacy, collaboration, and more.

**

Audrey Meyers: What is your connection to the midwest?

Barbara Browning: I was born in Madison, Wisconsin. My mother was born in Pontiac, Michigan, and my father in Elyria, Ohio. My parents separated when I was six, and when I was twelve my mother, sister and I moved to Northern Virginia, but I think my early years in Wisconsin, as well as my mother’s sensibility, were pretty determinant of something in my voice as a writer.

I’ve made reference to that in each of my novels. In The Correspondence Artist, the narrator says very early on, “my own voice has a certain Midwestern flatness about it. Perhaps you’ve already noticed that.” Actually, she says that on the first page of the book. And indeed, I think by the time they get to that line, readers will already have noticed what I’m talking about. The narrator of my second novel, I’m Trying to Reach You, was different from me in some respects (among them, gender), but we had in common having been raised by a single mom from the Midwest. Barbara Andersen, the narrator of The Gift, also references the Midwest quite a bit. My own mother and sister both ended up returning to Wisconsin, and live there now. Barbara A.’s mother and sister live in Ohio.

AM: How has being a professor at NYU impacted your writing?

BB: I had to introduce myself at an academic talk the other day and I began it by saying “I have the OBSCENE pleasure of teaching in the Department of Performance Studies at NYU.” That’s not actually an exaggeration. I’d been teaching performance theory and research methodologies for some time before I began writing fiction, so unlike a lot of fiction writers, who teach as a way to support their writing practice, which comes first, I began with a desire to teach, and then developed an interest in writing fiction as a way to expand what I was able to do in thinking about the theoretical, aesthetic and political questions in the areas of performance that move me. My students are brilliant, curious, brave, weird, and constantly turning me on to new music, dance and writing. My colleagues are also very precious to me. I end up inspired by them and quite a few have made at least cameo appearances in my writing.

Higher education today is a confusing place to be if you have certain political commitments. That is, it can be a very comfortable sphere, in some ways, if you lean leftward, but in many institutions, including my own, that’s undergirded by the crushing debt incurred by many students. So I think it’s important to keep challenging that, and talking about it, and grappling for ways to address that. It’s a part of the narrative of The Gift.

AM: What inspired you to write The Gift?

BB: In the book, my narrator explains that her readings of theorists of gift economies (Marcel Mauss, Lewis Hyde, David Graeber) in the wake of the Occupy movement inspire her to try an experiment – recording little ukulele cover tunes and spamming people with them in order to possibly stimulate a gift economy of purely sentimental value. I actually did that. And it’s kind of supposed to be funny, but it was also kind of serious. The part about valuing sentimental value over monetary or even aesthetic value was, I suppose, the feminist intervention. My own experiment led to a story very similar to Barbara Andersen’s. It was exhilarating, heartbreaking, scary, and poignant.

AM: What is significant about the virtual world in your book? How do you use it to explore the universal human condition?

BB: In all of my novels, the internet plays a big role – through the email correspondence of my narrator in The Correspondence Artist to the YouTube obsessions of my narrator in I’m Trying to Reach You to the swapping of digital sound and video files between my characters in The Gift. In all three cases, I actually made the digital files (and YouTube pages) that were reference in the texts. I think it’s important to acknowledge that the way we read now has changed. Even when one’s reading novels that don’t reference digital culture, we have a tendency to pause to Google something, and especially when there’s a blurry boundary between “reality” and “fiction” as there is in much of my writing, one has a tendency to want to go down certain rabbit holes. Of course, rabbit holes can be dangerous things. What I always try to encourage my students to do is to toggle between analog and digital. Your question asks about “universality,” and I’m not sure that’s exactly what I’m pointing at, although I also think that questions like the blurry boundary between reality and fiction are hardly new! Cervantes was asking the same kinds of things.

AM: It is thought-provoking that you investigate human interaction by sharing your music to no one in particular through emails. How do you express these connections through words and music rather than other sensory experiences that happen in person?

BB: Ironically, sometimes the voice recorded feels more intimate than the voice in a live conversation, say, in a café. I’m just finishing recording the audio novel version of The Gift, and I’m very self-conscious about my recorded speaking voice. The character Sami in the novel sends the narrator long recorded voice messages. Sometimes those feel even more naked or intimate than a physical encounter might. Sometimes we lose sight (or sense) of that in recorded music, because of the layering of sound or the way production can smooth out the edges – what I describe as the sound of the spit on the lips or the hairs in the nose when you listen to certain recorded voices. I think I say, “It’s almost like somebody’s sticking their tongue in your ear.” I find it interesting to acknowledge how intimate that experience can be.

AM: What did you learn about yourself as a writer when creating The Gift?

BB: Well, I think I knew this already, but this novel was the one in which I really had to confront my sense of obligation to the people in my life who end up incorporated into my fiction. That is, I always ask them to read drafts, and tell me what they’re comfortable or uncomfortable with, even if they’re not recognizable as themselves. I don’t hold that up as an ethical standard for anybody else – in fact, I don’t know of anybody who’s as obsessed with that as I am. For better or worse, it’s a compulsion.

AM: What do you hope people take away from your book?

BB: It’s funny, I had a feeling people would focus on the drama of the relationship with Sami, and the question of whether love at a distance is fulfilling, which isn’t a bad question, but isn’t really the most interesting one to me. I was hoping some of the political questions raised by the book might be of interest – and to my amazement, in fact, early readers seem to be responding to those. That is, I’d like for us, in this moment of great political anxiety and, for many of us, despair, to hold on to some hope, and maybe even utopianism.

AM: Why do you infuse music into your book? In other words, how does music relate to the purpose of your book? And how did this impact your writing style?

BB: Most of the ukulele cover tunes I mention in the narrative are archived on my SoundCloud page (https://soundcloud.com/barbarabrowning). There’s also a Vimeo page (the book has the site and the password in it) where the dance videos are archived. As in all my work, sometimes the music and dance inspires the writing, and sometimes it works in the other direction. Some readers seem to access this work, and others just want to imagine it. That doesn’t really bother me, though I’m always happy if someone told me they took a look or a listen…

AM: After creating The Gift, what does it mean to you to be an artist in the modern world?