Interview: Amanda Kabak

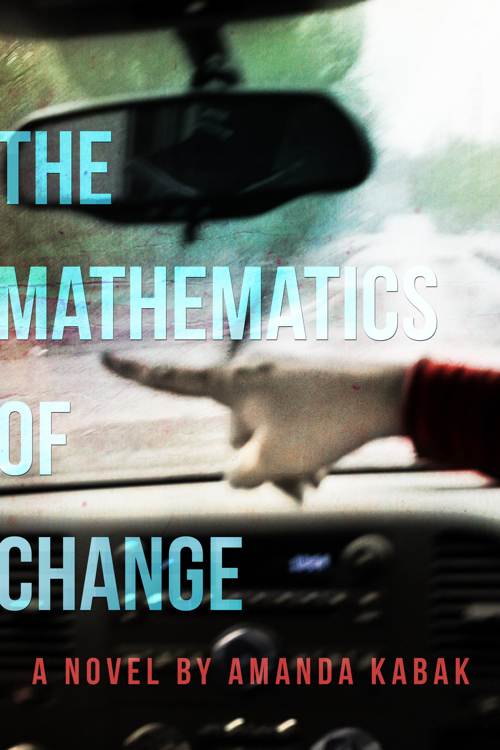

Midwestern Gothic staffer Audrey Meyers talked with author Amanda Kabak about her novel The Mathematics of Change, the complications of transitions, not being able to connect, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Audrey Meyers talked with author Amanda Kabak about her novel The Mathematics of Change, the complications of transitions, not being able to connect, and more.

**

Audrey Meyers: What is your connection to the Midwest?

Amanda Kabak: I grew up in a suburb of Chicago then went to high school in another suburb (or, I should say, at the edge of another suburb – it was mostly corn fields at the time). After high school, I made a great escape to Boston and swore I would never return to the area. 16 years later, I shocked my parents by moving back – to downtown Chicago this time, where I lived for 8 years until I recently moved again.

AM: How has living in the Midwest impacted your writing style?

AK: Growing up, I never quite felt comfortable, not in my own skin, not with my peers, not with suburban Chicago’s uninspiring landscape. I always wanted to get away, either someplace else physically or deep into my own head, but disappearing was practically impossible at that time, in those places, around people who were into everyone else’s business. When I moved to Boston, I felt at home for so many reasons: being in a city instead of a suburb, being around “rude” people who weren’t interested in me or in chatting out of supposed friendliness, the Berkshire Mountains in Western Mass and their welcoming beauty. It wasn’t until I moved there that I fully understood how foreign I had felt before, and it is this feeling of being an outsider, of not quite being able to connect, that informs so many of my stories and characters.

AM: What inspired you to write The Mathematics of Change?

AK: I write in coffee shops almost exclusively, and there was one I used to frequent in Boston where I sometimes saw this woman who was androgynous in the exact way I always wished I could be: tall, whip-thin, angular-but-not-unfriendly face. I have long been a denizen of the in-between, and I admit I was fascinated by this creature, who used to snag a table with her girlfriend to study. She took up a sort of permanent residence in my mind, but it was a couple of years before I built a character around her constellation of physical traits. Not just the traits, but unpacking what those traits mean to those around her, what they may have meant to her own personal history.

AM: What did you learn about yourself as a writer when creating this book?

AK: My whole experience as a writer is a bit of a cosmic joke. I lack both patience and the bent toward perfectionism that helps ease the path over the last 10% of any project, and writing requires both. Writing novels even more-so because the whole process is so prolonged. And yet, I am not myself when I’m not immersed in a long-form writing project. I get antsy and irritable and annoyed each time I reach the end of a short story and have to come up with another idea.

AM: Why are the themes of balance and change important aspects of your book? How do these two concepts interact in your character’s world?

AK: At my last job, my boss started to quote me: “As Amanda says, change is inevitable.” But that doesn’t make it easy, especially on an emotional level. When that change sparks self-reflection and doubt, it is even worse. Yet what are we to do? Entropy tells us, in a sweeping, metaphoric way, that there is no going back, but if change comes too fast for adaptation, we’re sunk as well. Enter the idea of balance. In the midst of change, we must balance holding fast to our idea of ourselves with reevaluating and adjusting. Both Mitch and Carol have these very deep-seated concepts of who they are – of how the decisions they have made in the past shaped what they feel is fundamental to themselves and maybe even their friendship, but they are forced to question this in very difficult ways.

AM: What character development traits are present during a midlife crisis? How did you explore these characteristics as your wrote The Mathematics of Change?

AK: I suspect mid-life crisis manifests differently for different people. I mean, I think I had mine at 19 or 20, but that’s another story. For Mitch and Carol, it is a reckoning. It is an outside force blowing through their lives that whispers, “Is this really what you want? Is this how you want the rest of your life to go? Can you imagine decades more of this?” It’s a frightening thought if you’ve successfully gone 20 or 30 years without much self-examination. There’s so much fear: what if I’ve made a terrible mistake and have to either live with it or try to rectify it? How have I hurt myself or others? How will I hurt myself or others if I try to change things? What will people think of me if I make a change? In the end, it is the attempt to answer the question of who we are at our core and, as a part of that, what is most important to us. Is it achievement? Connection? Family? Happiness?

AM: What drew you to writing about the complications during the transitions of life?

AK: Isn’t life just one transition after another? Over the last 15 years, I’ve had 8 jobs, lived at 7 different addresses in 3 different states, went from being the youngest at whatever company I’m working for to one of the oldest. The only consistent thing has been my sweetheart, and thank god for that! Change forces your hand, removes momentum from the equation, and that’s when things really get interesting.

AM: What life experiences helped you most to gain an understanding of the human condition?

AK: As I’ve said, I’ve always been something of an outsider – in one way, shape, or form. When I was younger, I was consistently just *flummoxed* by other people. They were maddeningly inconsistent, opaque, slippery chameleons. For a long while I was sure I would never understand someone or be fully understood in response. But then I was – or at least thought I was – and then, well, you can guess. Heartbreak is both universal and particular, and working through that was a formative experience for me. It is part of the human condition, as is the experience of being a prisoner of your past. That may be true, but I’ve also learned that despite history and trauma, we abdicate control of our own minds, emotions, reactions, and behavior at our own peril. So much of life is a tug of war between the ego and the id, but gaining mastery over ourselves is at the root of life, don’t you think? Moving consciously through your day, weaving kindness into your interactions (both to others and to yourself), seeing where you need to improve and tuning yourself like an instrument into something better, more gloriously resonant.

AM: What do readers take away from your book?

AK: At the very least, they probably end up knowing more about friction than they used to! But also that you must bend or you’ll break. Oh, and that forgiveness is at the root of change.

AM: What genre would label The Mathematics of Change?

AK: My publishers say it is “new women’s fiction,” but I think of it as straight-up storytelling. There’s something in it for many people, not just women, not just lesbians, not just mothers, not just people of a specific age.

AM: What techniques do you use as a writer to create authentic relationships between characters?

AK: I think of the inevitable gulf between what we think and what we do, what we intend and what actually happens. I write about people who want to be quality human beings but who make decisions that undermine themselves and hurt other people. I drive through dialog past what I intend to where someone says something wholly unanticipated and game-changing. And I get it wrong for about twelve drafts (during which time I think I get it right several times before realizing I’m deluded) until I find the contradictions and idiosyncrasies that make characters fully-realized people. Once that’s in place, when they interact with each other, those interactions will ring true.

AM: What do you enjoy most about being a writer?

AK: For me, writing is communication distilled then expanded. It is taking something so particular and laying down words and sentences and scenes that can evoke that specific experience in a universal kind of way. It is the challenge of pulling someone into a life wholly unlike their own but having them feel this “ah” of recognition. It is the daily exercise of submerging myself in the world I’m creating and the craft of staring out a window or over a barista’s head, trying to deeply imagine, trying to find the just-right word, trying to make this fuzzy thing that sits in my peripheral vision as starkly real as I can.

AM: What’s next for you?

AK: After four years, I’m finally putting the finishing touches on my next novel, and I’ve got one percolating in line behind it, so I guess you know where you’ll find me for the next few years!

**

Amanda Kabak