Interview: Tom McAllister

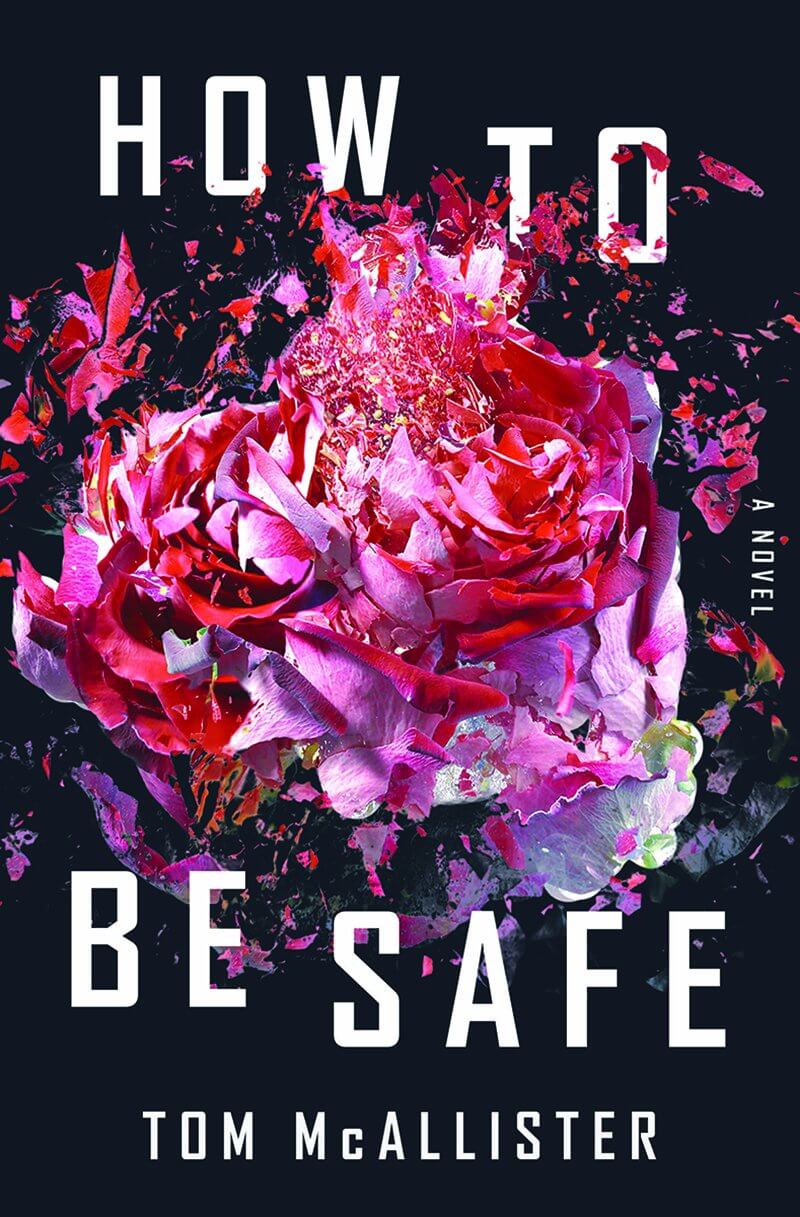

Midwestern Gothic staffer Elizabeth Dokas talked with author Tom McAllister about his novel How to Be Safe, media interactions with tragedy, social media and online life, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Elizabeth Dokas talked with author Tom McAllister about his novel How to Be Safe, media interactions with tragedy, social media and online life, and more.

**

Elizabeth Dokas: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Tom McAllister: I lived in Iowa City for two years when I was in graduate school. Prior to that, I had only been as far west as Gettysburg by car, and had once skipped over the rest of the country to go to California with my parents.

I have fond memories of my time in Iowa City, though I was personally not doing well then: I was just out college, and in a long-distance relationship, and still not over my father’s death, and I was not emotionally prepared for any of it. Mostly what I did when I was there was drink cheap pitchers of beer and talk about what I would do with myself once grad school was over.

But I also got engaged in my Iowa City apartment, and I made a lot of great friends there, and I learned so much that didn’t actually register with me until years later, when I was ready to start listening.

I haven’t been back since, though I’d love to go. I have been to Wisconsin on four different occasions in the past three years, and have found it to be a really wonderful place.

ED: Your newest novel, How to Be Safe, is set in a small town. From a writer’s perspective, how is crafting a distinctly small town setting distinct from a larger city or even a slightly larger town?

TM: I grew up in Philly, and have always identified myself as a Philly guy, though I’ve lived in the New Jersey suburbs since 2006. My town isn’t small, but it’s small enough that I see a lot of the same people around now, and I wonder whether they notice me, or why they would even care. There are still enough people here that I can disappear and blend in, which is a relief for me.

When I was writing the small (fictional) town of Seldom Falls, PA, I was thinking about a place on an even smaller scale than this. Because I was beginning with a school shooting, one thing I wanted was for it to be in a place that’s small enough that everybody knows everybody. Or they think they know everybody. Or they know just a little bit about most of the people. It doesn’t make the event any more tragic than if it happened in a major city, but it feels even more weirdly personal to the people there. It wasn’t just some teenager who died, but Sara, the girl you know from around the corner, whose mom is nice and works at the deli. I really liked the idea of integrating these little bits of biography into the book, and I think that’s an essential part of a small town’s character.

ED: How to Be Safe revolves around many modern political and social concerns, with gun violence at a school taking center stage. Did you have a particular situation in mind when exploring this type of gun violence (school shootings), or did you want to separate the narrative arc from real life occurrences? Why?

TM: I started working on this just after the Sandy Hook shooting, but I didn’t want to hew too closely to any specific event. I read Columbine by David Cullen and One of Us by Asne Seierstad, and I had always closely watched the real stories of mass public violence. They all tend to follow very similar patterns, which we sadly know so well by now. I didn’t want to too closely imitate any specific news story, but they all influenced it. One non-shooting story that had a big impact on this book was the aftermath of the Boston Marathon bombing, when people on reddit tried to solve the case by zooming in really closely on blurry photos, and nearly ruined some poor kid’s life by declaring he was probably the bomber. That really helped me to find the entry point to the novel, as Anna is falsely accused, for no good reason, of being involved in the shooting at her school.

ED: Much of this book also explores how issues of gun violence in society interact with the media, often butting up against issues of representation, skewing of facts, and victimization — of actual victims or not. What about media interactions with tragedy felt integral to you in portraying that tragedy?

TM: This ritual we go through is insanity. It’s incrementally worse every time. As I type this, a prominent conservative media figure is being boycotted because she taunted a literal child on Twitter because she’s angry at him for protesting guns. But even before David Hogg made gun people lose their minds, the media cycle was destroying us. There’s this desperation to churn content as quickly as possible, so after the shooting, the media descends and just chews people up and moves on the second there’s a new tragedy. They look very serious while they’re doing it, but they’re picking the bones of the town clean. It’s horrible to watch. I wanted the novel to address that dynamic clearly and directly, not to blame the media for the crimes, but to really dig into the ways our media culture is ruining our brains.

ED: How do you write a narrative about political issues that doesn’t devolve into political caterwauling, or a rehash of your own political views?

TM: This was really hard for me. Because I didn’t want to write a book that amounted to propaganda. I wanted it to be complex and compelling and difficult and all the other things you want from a novel. But also I have really strong feelings on all these issues. For me, the solution came in centering on this one specific voice, this woman who is specific and weird and funny (I hope) and angry. It let me channel some of my own anger and anxiety through her, but also forced me to shape the story around her and focus on narrative. I had to get deeply into her story and be faithful to it, wherever it took me. I don’t think I could have pulled that off if I’d gone with an omniscient narrator; I needed some constraints to make it work.

ED: Much of How to Be Safe explores how feminism and misogyny function in our society, and the main character, Anna, is a woman. As a man, did you find writing a female main character difficult? Did you find writing about experiences she had specifically as a woman difficult?

TM: It took me a long time to settle on the POV character and the voice for this book. Once I found the rhythms of Anna’s voice, I still resisted it, because I was very afraid of totally screwing it up. I’ve read and loved many books by and about women, but wasn’t sure I could do it myself.

When I’m deep into a project, I talk to my wife about it a lot, and in this case, I often ran scenarios by her to understand how she might perceive a situation differently than I would. When we walk into a crowded room for a party, what things does she notice right away (especially things that I might miss or take for granted)?

But also, the most important thing was Twitter, and social media in general. Just logging in every day, following smart and funny women, resisting the dumb urge to constantly respond to them, and just listening. Learning about the various indignities most women face day to day. Especially listening when they shared stories of male writers totally misunderstanding the internal lives of women.

ED: What did you find important about writing a female character to experience these conflicts? What was more potent, to you, than featuring a male main character in the same setting?

TM: It took me a long time to realize that school shootings alone aren’t the thing that’s upsetting to me; it’s a question of vulnerability. It’s about power and helplessness and being afraid in public. I’m a member of a lot of privileged groups, and so, even though I feel that vulnerability, I experience the world differently than lots of other people. I thought a women’s perspective would give me more access to this conflict, and also be a more honest telling of the story.

ED: What were your inspirations for this novel? Are these issues that bother you personally, or did you pull it more from what the larger public is concerned with? How do those inspirations affect your writing?

TM: This book is a big bundle of my obsessions and fears rolled into a weird little ball. Parts of the How to Be Safe chapters were pulled from an essay I’d worked on and abandoned years ago. The stuff about gun violence has always driven me crazy, especially since I teach at a large state school where something like this could happen any day. The randomness of a public attack (with a truck, gun, bomb, whatever) is terrifying to me, and I can’t find a way to feel okay about it. And the overheated rhetoric of the book, the push toward absurdity, comes from spending my life immersed in the hot take cycles of online life.

ED: What’s next for you?

TM: I have about 11 pages of a Word document written on something I’m refusing to call a novel until it turns into something else. I’ve struggled with it so far; it’s one of those things where I had a basic idea, but every time I try to get it started, it’s just not working. It’s also possible I’m avoiding seriously working on it because I don’t want to commit to another big project again.

I would really like to be able to write a book of nonfiction, but a) I only have the vaguest ideas for the focus of it, and b) I’m not sure anyone will let me do it. But I really enjoy exercising that part of my brain, and it’s been a while since I’ve worked seriously on longform nonfiction.

This is an unsatisfying answer, I realize.

**

Tom McAllister is the author of the novels How to Be Safe and The Young Widower’s Handbook, as well as the memoir Bury Me in My Jersey. His shorter work has been published in Best American Nonrequired Reading, The Millions, The Rumpus, and Hobart, among others. He co-hosts the Book Fight! podcast, and is nonfiction editor at Barrelhouse. He lives in New Jersey and teaches at Temple University.