Interview: Betty Moffett

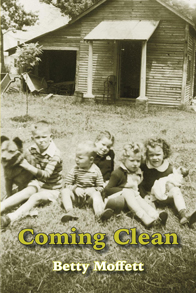

Midwestern Gothic staffer Jo Chang talked with author Betty Moffett about her book Coming Clean, fictionalizing facts, learning from her students, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Jo Chang talked with author Betty Moffett about her book Coming Clean, fictionalizing facts, learning from her students, and more.

Jo Chang: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Betty Moffett: My original connection to the Midwest was Grinnell College in Grinnell, Iowa, since, in 1971, my husband signed a contract to teach theatre there. (I had to look on the map to find Iowa.) Since then, of course, my connections have multiplied. I have strong attachments to friends, the land, the town, the little string band my husband and I play in, the memories of our son growing up here. I could make a very long list.

JC: Initially, you and your family planned to move back to the South after a year in Iowa; however, you found yourself staying. What is it about the Midwest that captivated you? How does it compare or contrast to the South? Did your ability to find inspiration change in accordance with the new environment?

BM: We loved North Carolina. We still do. When we first moved to Iowa, I thought I might fall off the Earth because there were so few trees to hold on to. Still, what captivated me first about this place was the land—the roll and richness of it (someone has called it ‘bosomy’) — and the fact that, as one student wrote, “You can tilt your head back and see nothing but sky.” And soon, as I got to know the people, I appreciated their kindness and steadiness. In the South, people are typically more effusive in their speech and manner than Midwesterners. In answer to “How are you?” my Southern friends might say, “Just fine,” or “Wonderful,” or even “Peachy.” In Iowa folks are more likely to reply, “Pretty good” or “Not too bad” — more cautious, less extravagant, a bit “steadier.”

I think contrasts between the South and the Midwest have allowed me to appreciate a variety of landscapes and attitudes. Before we left North Carolina, I asked my favorite grad school professor if he’d ever heard of Grinnell College. “Oh yes,” he said. “It’s a good school. But you know that if you go there, you’ll give up everything that being Southern means.” I’m still trying to figure out what it means to be Southern, and I don’t believe I’ve given up a thing. And now I have two places to call “home.”

JC: Your forthcoming book Coming Clean, is both memoir and short story collection, weaving details from your own experience into short stories; missing children and successful cowboys inhabit worlds set in both North Carolina, where you were raised, and Iowa, where you currently reside. As Coming Clean contains biographical events that have been fictionalized, was it difficult to work with subject matter that is both personal and factual, and the fictional elements that transformed them into short stories?

BM: I’ve never had trouble fictionalizing facts — for two main reasons:

-

- The stories I grew up hearing from my parents, aunts, and uncles were always a combination of fact and fiction. If a story was a good one, it would be requested again and again (“Tell the one about the dog/horse/fire in the barn.”). And each time, some detail, some ‘fact,’ would change. “The Store,” the first story in Coming Clean, comes from my father, who was the boy in the store. As a child sitting on my grandmother’s front porch with the family, I’m sure I heard that story at least 10 times — and never the same way. No one objected; no one corrected. We all knew Daddy was just making the truth better.

- I can’t write pure fiction. I can’t make up people and places that never existed, that I know nothing about. All my stories start with something I’ve heard about or experienced. But I’m not a historian, either. Of the ‘Who, What, When, Where, and Why,’ questions, I’m not especially interested in the ‘When’ or ‘Where.’ And my ‘Who’s’ are likely to be a combination of people, the ‘Why’s’ tailored to fit the shape of the story.

As some smart person has said, “History is objective and dispassionate.” I prefer subjective passion.

JC: What was the research process like? Was it mostly self-reflective, or did you find yourself asking family and friends for details?

BM: I have done precious little research for Coming Clean (see above). What happens to the people in these stories (whether it actually happened or not) is so real to me that I have all the necessary details — or I make them up.

JC: As an instructor at Grinnell College, do you think that your students have influenced your writing? If so, how?

BM: My students in Grinnell’s Writing Lab and in the classes I taught at the college influenced my writing in many ways. They made me more conscious of individual words, of precise meaning. I remember a very pleasant hour with a young woman from Japan who was curious about the word ‘just’: “I understand how it functions as an adjective — as in ‘a just law’ [she knew her grammar]. But what does it mean as an adverb — as in ‘I’m just fine’?” Good question! And a sunny and severely dyslexic young man in my composition class broke my heart as he struggled to read and then to write an essay on Orwell’s “Shooting an Elephant.” But when, as a kind of break, I asked the class to write short stories, he produced a clear and powerful piece about a dangerous party he’d attended. He was writing his own material; he was in control; he believed he could communicate. He was right, and the realization carried over to his more academic work. I learned from him.

JC: What is one thing that you wish you were told when you first began writing?

BM: I remember and am grateful two very different teachers who commented on my writing. Mrs. Walker, my high school English teacher, wrote on one of my papers, “Someday, you will write a book.” Miss Jones, who taught my first college English class, wrote on a story I handed in, “I do not believe this is your original work.” Although I loved Mrs. Walker and did not love Miss Jones, I decided to accept both comments as compliments, and was pleased with both reactions. I believe that people generally respond better to praise than to criticism, and this applies particularly to writing. Anyone who says, “Don’t take what I say about your (essay/poem/research paper/short story) personally” is not a sensible person.

JC: What is your writing process like? Since Coming Clean is a collection of short stories, did you find yourself focusing on one story at a time, or working on sections of multiple ones at once?

BM: I can only work on one story at a time. When it’s going well, it’s very exciting and I can’t wait to sit down and keep going (I do not forget to eat.) When it’s going badly, I get discouraged, but if I take the dog for a walk and then come back to revise, it usually gets better. I’ve only quit on a couple of stories.

JC: What’s next for you?

BM: After Ice Cube Press publishes Coming Clean in October, I look forward to doing a number of readings and at least one workshop. Then, I’d like to read three or four middlebrow mysteries. And then, I want to get back to writing stories.

**

Betty Moffett was born, educated, and married in North Carolina—and then successfully transplanted to the Midwest. After teaching for nearly 30 years in Grinnell College’s Writing Lab (in Grinnell, Iowa), she is now trying to take her own advice. Ice Cube Press will publish Coming Clean, a collection of her stories, on October 5 of this year. Her stories have appeared in various magazines and journals, including Bluestem, The MacGuffin, The Broadkill Review, The Wapsipinicon Almanac, and The Dead Mule School of Southern Literature. She and her husband play with and write songs for the Too Many String Band.

You can pre-order Coming Clean (ISBN 9781948509022) for $19.99 on Ice Cube Press’s website.