Interview: Brian Laidlaw

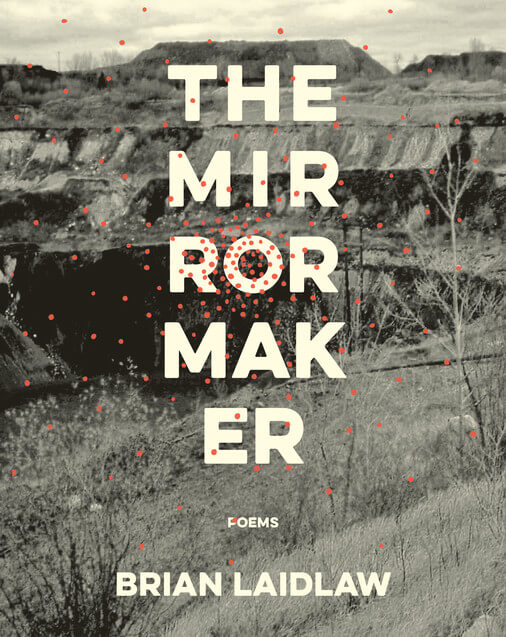

Midwestern Gothic staffer Jo Chang talked with author Brian Laidlaw about his collection The Mirrormaker, incorporating music and songwriting into poetry, retelling historical myths, & more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Jo Chang talked with author Brian Laidlaw about his collection The Mirrormaker, incorporating music and songwriting into poetry, retelling historical myths, & more.

**

Jo Chang: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Brian Laidlaw: My dad is from Minnesota, so I’d visited a few times as a kid — the lightning storms left an impression on me — but my own Minnesota roots didn’t really sink in until I moved to Minneapolis in 2008 to begin an MFA in Poetry at the U of M.

I had expected to complete my degree and then hightail back to the West Coast, but I found that the literary and music community in the Twin Cities was something genuinely remarkable — unimaginable, really. The institutional support and public funding for the arts, along with a fantastically attentive and enthusiastic audience, made it an ideal place to be.

So I made it the more-or-less permanent home base for my career…. My publisher, Milkweed Editions, is based there, and I continue to do tons of performances, workshops, and community-based collaborations, both in the Twin Cities and in the (amazing and beautiful) rural parts of the state. I spend quite a lot of time on the road at this point, bouncing between Minnesota, Colorado and the West Coast, but it’s always a calm and joyous homecoming whenever I return to the Land of 10,000 Lakes.

JC: As someone with ties to both California and Minnesota, regions that seem to exist on opposite ends of the spectrum, how has your experience with space and place affected your writing and/or creative processes, if at all?

BL: For better and for worse, I’m beginning to realize that all my writing is profoundly place-based. Although I don’t write exclusively “about” landscape, the landscape has near-total control over the texts I produce: my geographic setting determines what books I choose to read at a given time, and shapes what activities I choose to do; it influences the way I make sense of those texts and adventures; and it shapes the way I synthesize them into poem-stuff and song-stuff.

So — because of their radically different climates, terrains, and rhythms — I find that I produce starkly contrasting work, depending on whether I’m in Minnesota or California (or someplace else in between.) The new book is all about the Iron Range, and it arose from spending quite a bit of time up in Hibbing, staying with various families, talking and collaborating with locals, and trying in earnest to digest the complex social, economic and geologic history of that area.

The glacial cold and (at least by comparison to my frantic Bay Area home) the glacial slowness of that place are certainly borne out in the style of the project…. The poems are a little more pulverized than usual, and the songs a little more sprawling. Hibbing is Bob Dylan’s hometown, and I think the aspect that excites me most about the project is that, by way of that landscape, the work shares a bit of the North Country-imprint that one hears in Dylan’s own writing.

JC: You incorporate elements of music and songwriting into your poetry; for example, your forthcoming book, The Mirrormaker, has a companion song suite that is available for download along with the book itself. Can you explain how music and poetry coexist and commingle in your craft?

BL: When I first started writing, my poems and songs were formally indistinguishable from one another; they were all highly regular and metrical, often rhyming-or slant-rhyming, often using some degree of repetition.

Over the years those crafts have diverged; I continue to love (to a highly nerdy degree) formal prosody, but now that side of my writing lives almost exclusively in my songs. My poetry, meanwhile, has trended in a more fragmentary direction — so I feel like I have widened my palette. Generally speaking, I’d say that for more linear or logical “arguments,” the sustained, tight, rigorous space of a metrical song is the right formal fit; for more uncertain inquiries, I’ve found that a fragmentary poetic form is better able to guide me into/through the unknown territory.

But this is always in flux: My challenge to myself now is to write more song-like poems and more poem-like songs, whatever that might mean.

JC: What inspired you to incorporate music into your poetic work?

BL: It was largely in counter-response to the way that mainstream audiences respond to poetry. I think that the national poetry conversation is exceptionally vibrant right now, but I think it’s also a fair generalization to say that most poetry — and especially most experimental / fragmentary / weird poetry — is read largely by other poets.

So I started composing these companion albums for my books as a way — hopefully! — to bridge the gap between the admittedly somewhat “difficult” poetic work, and those readers who might be unfamiliar with this style of contemporary poetry. The songs are a kind of “gateway drug,” I guess, to establish some of the book’s thematic concerns in a more user-friendly medium — and provide some context in which to ground the poems.

That’s part of it. The other part is that, once I’m in a place and doing the research for a project, my creative output is never only poems or only songs — so it makes sense to present the poems and songs in tandem, because in my mind it’s all the same body of work.

JC: Your forthcoming book, The Mirrormaker, is a companion work to your previous project, The Stuntman. What made you decide to expand on The Stuntman?

BL: I actually began The Stuntman and The Mirrormaker at the same time; they both took shape out of an immense stack of poems and repertoire of songs that I had written during various research trips and musical tours on the Iron Range. It was clear that there was far too much for a single volume (I had almost 400 pages of material), so I separated out a cluster of the work that was internally coherent (and Dylan/Narcissus related), which became The Stuntman.

At the same time, I also set aside another manuscript’s-worth of poems (and album’s worth of songs) that, after quite a bit of re-sequencing and revision, would become The Mirrormaker.

JC: The Mirrormaker, as stated above, expands on the previous retelling of the myth of Echo and Narcissus, along with another famous couple, Bob Dylan and Echo Helstrom, to explore topics such as celebrity, history and myth, love and loss, and, to quote the publisher, “[pits] romantic obsession against self-obsession.” What piqued your interest in these two famous couples, and what particular similarities stuck out to you in the beginning stages of the project that made you decide to explore the dynamics between both?

BL: At that time I was taking my first dive into contemporary ecocriticism and ecofeminism, some of which suggests that “Nature” is a construct onto which (Western) humans project their own values and desires. In this way the landscape becomes a kind of mirror for its inhabitants; the residents, rather than genuinely seeing their environment, see only a reflection of themselves.

During that reading, it had occurred to me that Echo is a perfect embodiment (or en-symbolment?) of this phenomenon; we often associate echoes with “natural” spaces like cliffs and canyons, and when we yell HELLO in those locations, it feels like nature is speaking to us when it yells HELLO back — but really that echo is nothing but our own voice. I had long observed that love songs work in almost exactly the same way: for all that the love-song singer purports to be focusing his/her attentions on the beloved, love songs usually end up revealing more about the singer than the “singee.” Again, the beloved is nothing but a mirror in which the singer reflects.

This all came together during a visit to Dylan’s hometown, shortly after I moved to Minnesota. The landscape there is stunning. At the edge of town there’s an overlook that gives onto an enormous red canyon which, mind-bogglingly, is manmade; it’s the Hull-Rust Mahoning Mine, the largest open-pit iron mine in North America. It set me thinking about the rhetoric that underlies extraction economies, like the iron mining industry in Northern Minnesota…. And I was also thinking about the way that songwriters like Dylan (and myself, and all of us) may be guilty of similar behavior when we write songs about the landscapes and people that we love — just like miners, we refer to our relationships, our family dramas, and our hometowns and upbringings as “good material.”

Strangely, it all clicked one night when I was sleeping in the basement of a friend’s house in Hibbing, just a few blocks from Dylan’s childhood home. I had an uncommonly vivid dream in which the basement window slid open and the figure of Echo crawled through — in my dream logic I knew that she was both the Echo from the myth, and also, in a gestural way, the real-life Echo who inspired Dylan’s tune “The Girl From the North Country.”

Although it took several years to come together, the book and the song cycle arose out of that dream.

JC: How do you find inspiration for both your music and your poetry? Does this process change according to each medium?

BL: It has taken me about a decade of doing this poet-musician life full-time, in order to understand the mechanics of the process… But I’m realizing that at this point the inspiration almost always originates in reading other writers and listening to other musicians. That’s the first step.

And then the second step is to work through those ideas in a more embodied — and less intellectual — way. The readings and listenings subconsciously filter through the experiences I’m having while on tour, or while hiding out in the woods or the backcountry, or while leading a workshop, or whatever it may be. But I’m realizing that the physical activity and the geographic movement are essential catalysts to the creative process — whether the eventual output is poems or songs.

JC: What’s next for you?

BL: Just last month I published my first-ever creative nonfiction piece, an essay about a desert hermit named Burro Schmidt who spent decades hand-drilling a tunnel through a mountain in the Mojave. It’s part of an essay collection that I’m working on, which I’m tentatively calling Vertical Pastoral, about the intersection between poetics and rock climbing/mountaineering.

So right now I’m doing a bunch of research about the history of alpinism and mountain aesthetics… I’m also a very enthusiastic and reasonably competent climber, so for the next year or two I’ll spend as much time as possible living in my little yellow school bus, reading about climbing, writing about climbing, and climbing.

**

Brian Laidlaw is a poet-songwriter currently based in Boulder, Colorado. He has released the poetry collections Amoratorium (Paper Darts Press) and The Stuntman (Milkweed Editions), each of which includes a companion album of original music; another book called The Mirrormaker is forthcoming from Milkweed this year. Brian is working toward a Ph.D. in Creative Writing at the University of Denver, and continues to tour nationally and internationally with his band The Family Trade. News, music, and tour dates are available at www.brianlaidlaw.com.