Interview: Samrat Upadhyay

August 3rd, 2017

Midwestern Gothic staffer Kathleen Janeschek talked with author Samrat Upadhyay about his collection Mad Country, intersections of Nepal and America, current event writing, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Kathleen Janeschek talked with author Samrat Upadhyay about his collection Mad Country, intersections of Nepal and America, current event writing, and more.

**

Kathleen Janeschek: What’s your connection to the Midwest?

Samrat Upadhyay: Midwest has been my home away from home for the past twenty five years. When I first landed in the U.S. on a cold January evening in 1984, it was in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, to attend school at Coe College. After one semester, I transferred to Ohio’s College of Wooster, from where I earned by BA in English. For my MA, I migrated three hours south to Ohio University in Athens, Ohio, where I earned a degree in Creative Writing. After I spent some time in Nepal and in Hawaii, my first tenure track job brought me back to Ohio, at Baldwin-Wallace College. Now for more than a decade I’ve been a professor at Indiana University in Bloomington. Although I can’t call myself a child of the Midwest, I’m certainly a student of the Midwest. And since I got my US citizenship while in Indiana, I’m a naturalized Hoosier.

KJ: Nepal and Midwestern America are undoubtedly very different places to live in. So what has been the most surprising similarity between the two?

SU: You know, my whole body of work is about seeking commonalities among people. When my first book was published, some reviewers seemed surprised that Nepalis were like Americans: they laugh, eat, worry about their children’s schooling, have sex etc. Speaking specifically of the Midwest, I think there is a openness and approachability to both Midwesterners and Nepalis. Midwesterners are friendly and helpful, and Nepalis are also warm and kind people.

KJ: Do you ever find your depictions of Nepal influenced by your experience in the Midwest?

SU: Living in the quietude of the Midwest has certainly sharpened my sense of Nepal. I am a writer who needs a distance – both of time and place – to write with clarity, and living this far away has enabled me to have perspectives that I otherwise wouldn’t have. More specifically, I was a poor student throughout my college career in the Midwest. In Nepal, I’d grown up middle class, and although my parents weren’t well to do, they’d made sure I didn’t feel any lack. So, this experience of not having enough in America was new to me, and I think it taught me important lessons about human experiences that I was then able to transfer to my Nepali characters.

KJ: When portraying Nepal to a primarily Western audience, what cautions do you take?

SU: I try to be as balanced as I can. I have certain views and opinions, but a work of fiction isn’t about my opinions but about the complexity of people’s lives I depict. Balancing doesn’t necessary mean I’m looking for the other side of the coin in each instance: it simply means turning inward to reach for the truth. Often that’s enough for a truthful and multifaceted portrayal. It’s a question of not blocking your own light.

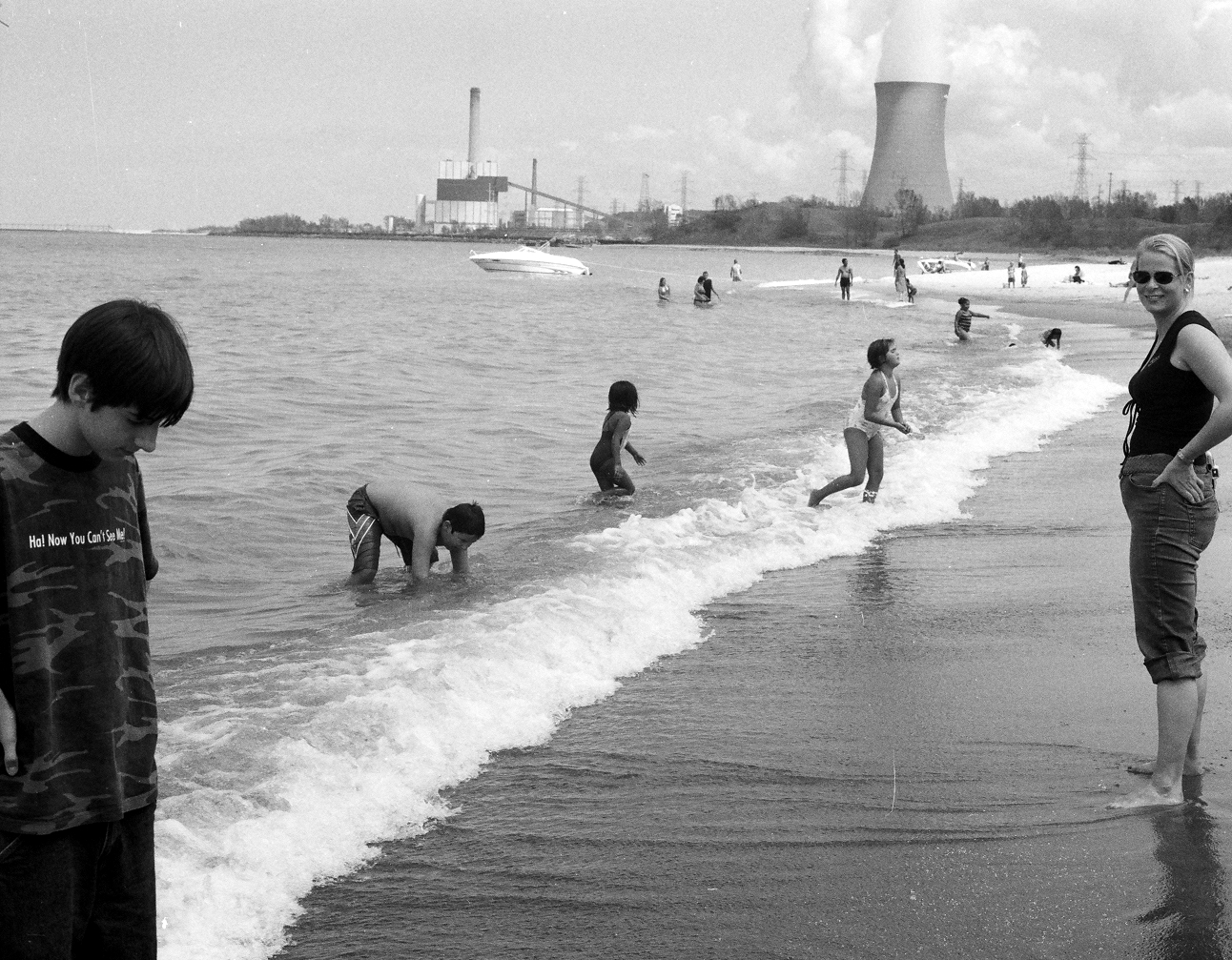

KJ: In your new collection, Mad Country, there is the story called “America the Great Equalizer,” which is your first story set in America. What made you finally decide to write a story set in America?

SU: “America the Great Equalizer” is my first story fully set in America, although in my previous work my characters have done some traveling to America. When I lecture or do readings in the U.S., my Nepali readers, especially the younger generation, have asked me why I haven’t written about them. My answer has been that Nepal’s hold on me is too strong to break. When Ferguson happened, I began thinking. Race issues in America tend to be couched in the binary of black and white, and the other shades of color are often not a part of the conversation. I envisioned a young Nepali student, with baggage from his own personal life, trying to come to grips with this big racial divide. It seemed like a natural extension of the other stories I was writing during that period. Many of these stories, although set in Nepal, also investigate the various identities that orchestrate our experiences.

KJ: Much of your work – including the previously mentioned story which centers around the death of Michael Brown and the subsequent riots in Ferguson – focuses on recent happenings. What do you consider the advantages and disadvantages of writing about current events?

SU: As I mentioned before, I do need some time and space in order to write about events. With Ferguson, I sensed an urgency, and I hope that urgency is communicated to the reader in my story. When you write about current events, what gets on the page can feel immediate and electrifying. The disadvantages of it are, of course, that you don’t have the wide-angled view, the third eye, that is crucial to a writer.

KJ: Likewise, many of your stories take place at the intersection between the personal and the political. What attracts you to these intersections?

SU: The personal is the political, as societal rules and consensus inform the everyday decisions of our lives. In the U.S. politics often doesn’t seem to matter in our personal lives, but even here you see that it’s the poor and the marginalized, and often the people of color, who are immediately affected by decisions made by those in power. In Nepal, politics feels intensely personal. During the Maoist civil war between 1995 and 2005 for example, even as a Nepali living in the U.S. I felt that it had invaded my personal space. When I spoke on the phone to my parents in Nepal, I’d hear fear in their voices, especially during the time when the Maoists targeted homes of those whose relatives lived in America. In my work, I am interested in how everyday people deal with the consequences of political decisions, how they manage to live, and sometimes live fully and richly, even in the midst of political crises.

KJ: What is the most important element of a sentence for you?

SU: That depends entirely upon what the sentence does. A sentence could purely functional, just to get the information across. Or it could emphasize mood and emotion. But I’m often on the lookout to see if a sentence can impart an image because images linger in the reader’s mind.

KJ: How do you keep your stories expansive and your language sparse?

SU: I like tight and lean – and sometimes mean – prose. The expansiveness has more to do with how you are looking (the vision) than what you are looking with (the medium). If your focus is narrow, then even when you employ expansive language, the focus will remain narrow. I do believe that language can empower us to become far-seeing, even though we might be quite nearsighted in real life.

KJ: What has teaching creative writing taught you about writing?

SU: That I don’t know everything, and that each classroom session is teaching me something.

KJ: What’s next for you?

SU: I am working on a novel. It imagines a radically different Nepal in the aftermath of the real earthquake of 2015.

**

Samrat Upadhyay (samratupadhyay.com) is the first Nepali-born fiction writer to be published in the United States. His debut short story collection Arresting God in Kathmandu was the winner of the 2001 Whiting Writers’ Award and his second short story collection, The Royal Ghosts, won the 2007 Asian American Literary Award. His first novel, The Guru of Love, was a New York Times Notable Book while his second novel, Buddha’s Orphans, was longlisted for the 2012 DSC Prize for South Asian Literature. His 2014 novel, The City Son, was longlisted for the PEN Open Book award. His latest story collection, Mad Country, has been called “brilliant” by Kirkus Reviews and “timely and remarkable” by Publishers Weekly. He is the Martha C. Kraft Professor of Humanities at Indiana University, where he teaches in its MFA program.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Meghan Chou talked with author Ian Bassingthwaighte about his book Live From Cairo, perspectives on the refugee crisis, the psychological toll of his work, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Meghan Chou talked with author Ian Bassingthwaighte about his book Live From Cairo, perspectives on the refugee crisis, the psychological toll of his work, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Audrey Meyers talked with author Lance Olsen about his book Dreamlives of Debris, the Minotaur myth, how to navigate a narrative, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Audrey Meyers talked with author Lance Olsen about his book Dreamlives of Debris, the Minotaur myth, how to navigate a narrative, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Audrey Meyers talked with author Amanda Kabak about her novel The Mathematics of Change, the complications of transitions, not being able to connect, and more.

Midwestern Gothic staffer Audrey Meyers talked with author Amanda Kabak about her novel The Mathematics of Change, the complications of transitions, not being able to connect, and more.

Our 2017 Flash Fiction Contest is sponsored by Audible. Get a free 30-day trial and 2 books, on us when you sign up.

Our 2017 Flash Fiction Contest is sponsored by Audible. Get a free 30-day trial and 2 books, on us when you sign up.